When I was getting started in boatbuilding, I struggled to understand how different small-boat shapes might perform and their level of difficulty in construction. I remember feeling nearly overwhelmed by a sea of foreign words and unknown concepts. It would have been nice to have had an illustrated guide to basic small-boat shapes: hulls, bows, sterns, and some terminology that defines form. So, if you are new to boatbuilding, or if you feel unclear on some of these basic concepts, this guide is for you.

From the moment man discovered that he could traverse a river on a floating log, boat shapes have continued to evolve. Early boats took on a wide variety of forms, utilizing any available material that could be made to float. Among these craft were rafts made from inflated animal skins, bamboo, papyrus reeds, and even terra cotta pots. Later came dugout canoes, skin, wood, and bone kayaks first used by Eskimo hunters, and basket-shaped coracles (also skin boats) built in Ireland and Wales.

While boat and ship building became refined over the centuries, early designers and builders still took a Darwinian approach: If a new ship returned from her maiden voyage, she might be copied and built again. If she failed to return, well, then she might not be reproduced.

We still haven’t conquered the sea, and I doubt that we ever will. However, we do have more tools at our disposal to help us build boats that are safer to use and perform better. Hours spent on construction represent only a fraction of time in the life of a small wooden boat. It isn’t difficult to grasp the utility of basic small-boat shapes, and it will be helpful to know something about them when choosing a boatbuilding project.

Please remember that this is an article about small-boat shapes, not small-boat design. While some overlapping concepts are mentioned here, we will not cover even the rudiments of what it takes to create a lines drawing. If this piece whets your appetite for learning something about small-boat design, then I encourage you to read Harry Bryan’s article on the subject in WB No.196, page 44, and to consider the titles provided at the conclusion.

The Origins of Hull Shapes

Hull shapes (in section) are made up of some combination of three basic forms. These are: flat-bottomed, V-bottomed, and round-bottomed.

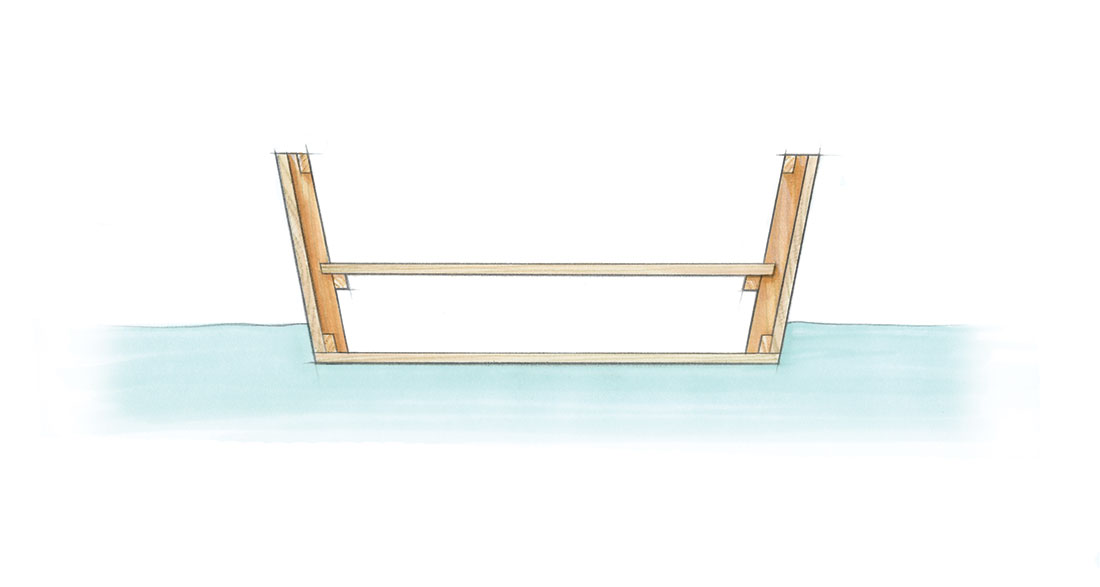

Flat-bottomed Form

Strengths:

The flat-bottomed boat’s principal asset is that it is easy to build. Therefore it is generally inexpensive for its size. It also has a lot of interior volume and can have good initial stability (and not feel tender, that is, tippy). The flat bottom shape is most often used for small rowboats, but many larger craft have also successfully used this most basic of forms. This skiff is based on a flat-bottomed form. The form is augmented by rocker, canted topsides, and a bit of flare in the forward section.

Weaknesses:

The flat-bottomed boat has some serious drawbacks, too. Its large, flat panels are hard to support structurally; when heeled too much, it can easily fill and capsize; and the flat bottom pounds even at moderate speeds in waves. Because of these drawbacks, the flat-bottomed boat shape is generally not considered as sea-worthy as the other basic shapes.

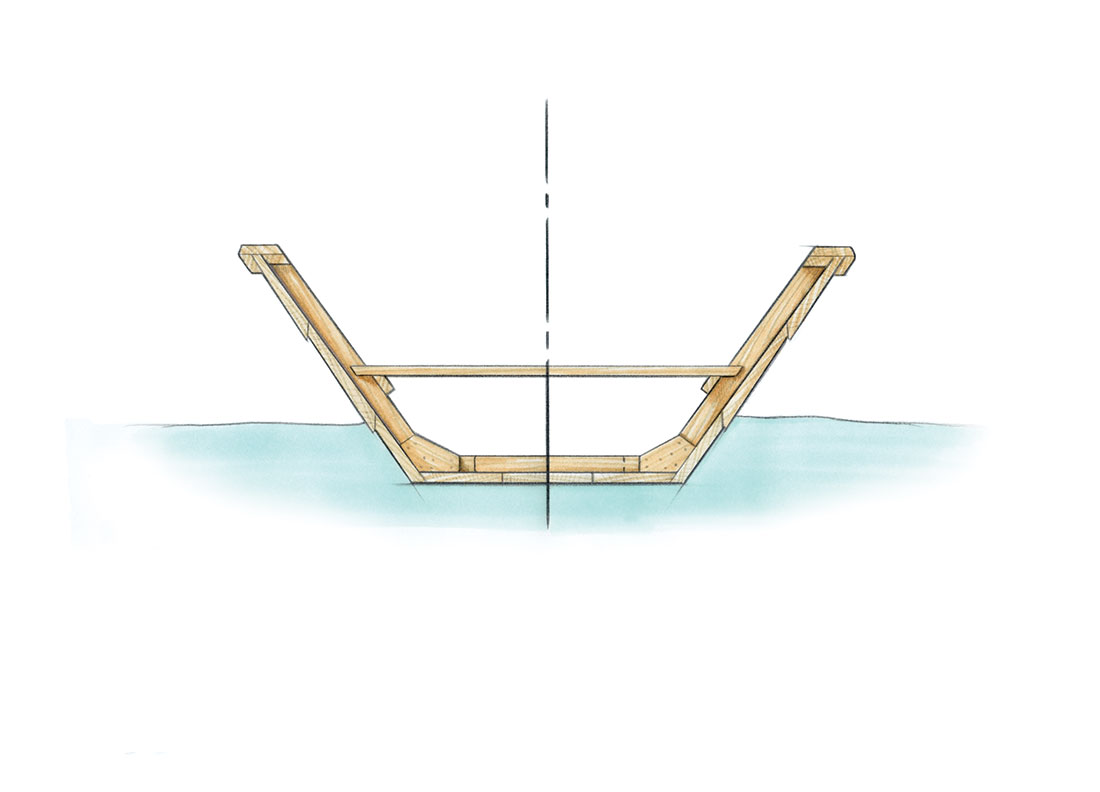

V-bottomed Form

Strengths:

V-bottomed boats, when properly shaped, can be inherently stronger than a boat with a flat-panel bottom and will slice through the water with much less pounding. Because of this, they are considered more seaworthy than equivalent-sized flat-bottomed boats. Boats and yachts of all sizes have been designed and built with V-bottoms. Virtually all high-speed power craft built today employ some type of V-bottomed shape.

Weaknesses:

In smooth water, V-bottomed boats require more power for the higher speed ranges than flat-bottomed boats do. Also, the V-shape offers greater difficulty in construction. Because of this, V-bottomed boats tend to be more expensive than the flat-bottomed type. Also, the V-bottomed boat may be less roomy, and harder to clean and paint than a similarly sized flattie.

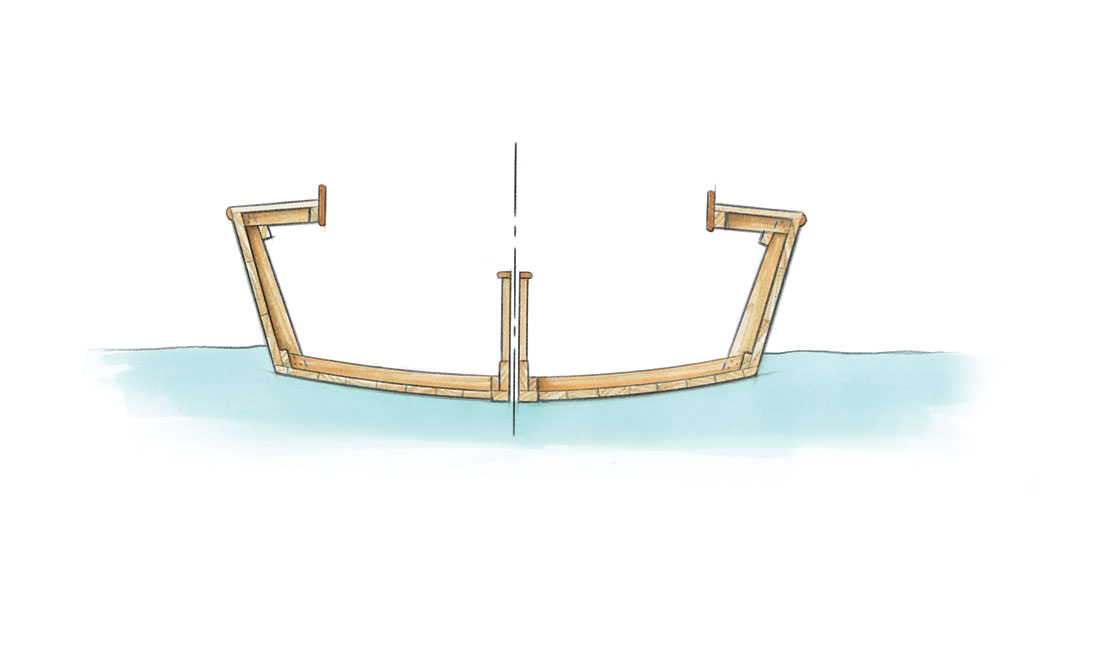

Round-bottomed Form

Strengths:

The curved shape of a round bottom is intrinsically strong and allows the boat an easier motion than its V-bottomed and flat-bottomed cousins. This shape is generally used for higher-displacement boats (displacement boats do not plane) that are designed to go at moderate speeds through the water rather than over it like the higher-speed V-bottoms can.

Weaknesses:

Round-bottomed boats are the hardest to construct and are, by far, the most expensive to build. Virtually all hulls borrow from these pure forms. Let’s look at some of the many elements of small-boat hull shapes and the characteristics that distinguish one from the other.

Scow

This simple-to-construct, flat-bottomed hull type tends to be a slow mover that will pound in waves, but it is very stable in calm waters on a breezeless day.

Dory

While both the flat-bottomed skiff (see illustration on previous page) and the dory (above) are somewhat more difficult to construct than the scow, their sweeping bottom shapes and canted sides enable them to ride the waves more easily than their slab-sided counterpart. A dory has some similarities to a skiff. However, it has a narrower bottom and transom, employs some different construction techniques, and is made for use in heavier seas. A dory’s flaring sides make it increasingly stable the more it is tipped, so while you might be alarmed at this boat’s initial nervousness, you may find yourself able to stand on its rail without water coming aboard.

Arc-bottomed Centerboard Sailboat

Of the flat-bottomed hull configurations presented here, the arc bottom is the most difficult to construct. It is also the most sea-friendly and comfortable of these flat-bottomed types.

V-bottomed Motorboat

The deadrise angle (see page 6) of the V-shaped bottom allows this hull shape to move forward through waves more easily than a flat-bottomed type, while still providing good stability. Many planing boats, such as runabouts, combine the deep V-bottom in the forward area of the boat, while unrolling the shape to a flatter deadrise angle toward the stern (as illustrated). This combination gives a boat the dual benefits of speed in waves and stability.

Multichined Kayak

Up to this point, we have not discussed chines. Chines are the intersections of the bottom and sides. All of the boats we have discussed so far are single-chined, meaning that they have only one hard turn, or corner, where the bottom meets the sides. The bottom of a multichined boat is made up of a number of narrower panels. Depending on the design, the multichined shape, as in the kayak shown above, can produce a hull whose performance approaches that of a round- bottomed boat.

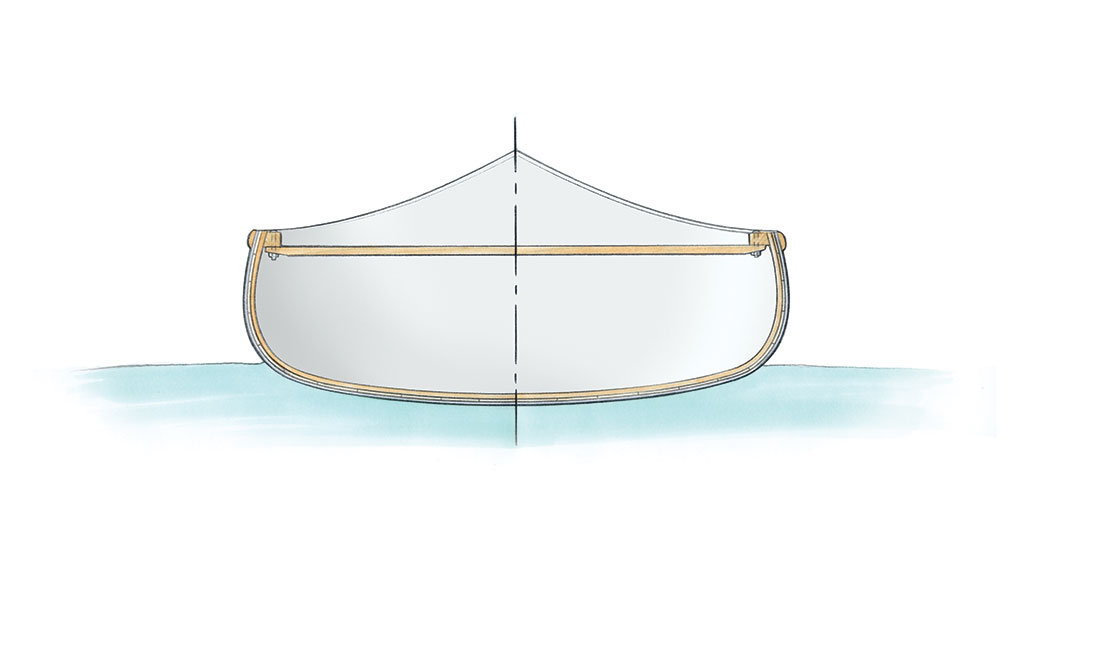

Round-bottomed Canoe

Round hull shapes are more difficult to build than either flat-bottomed or V-shaped hulls. Often, flat-bottomed or V-shaped hulls can be built on their own permanent frames, or their frames are easily sawn and fitted. A much more complex mold system must be set up before a round-bottomed hull can be built. For a well-constructed round-bottomed boat, the builder must have a higher level of woodworking skill and a good understanding of wood characteristics. Yet round-bottomed boats are the usual preference of people who spend a lot of time on the water. Why? Partly because this shape responds to the undulations of the water more gracefully than any other type of small boat. Also, they tend to be more comfortable and many people prefer their looks.

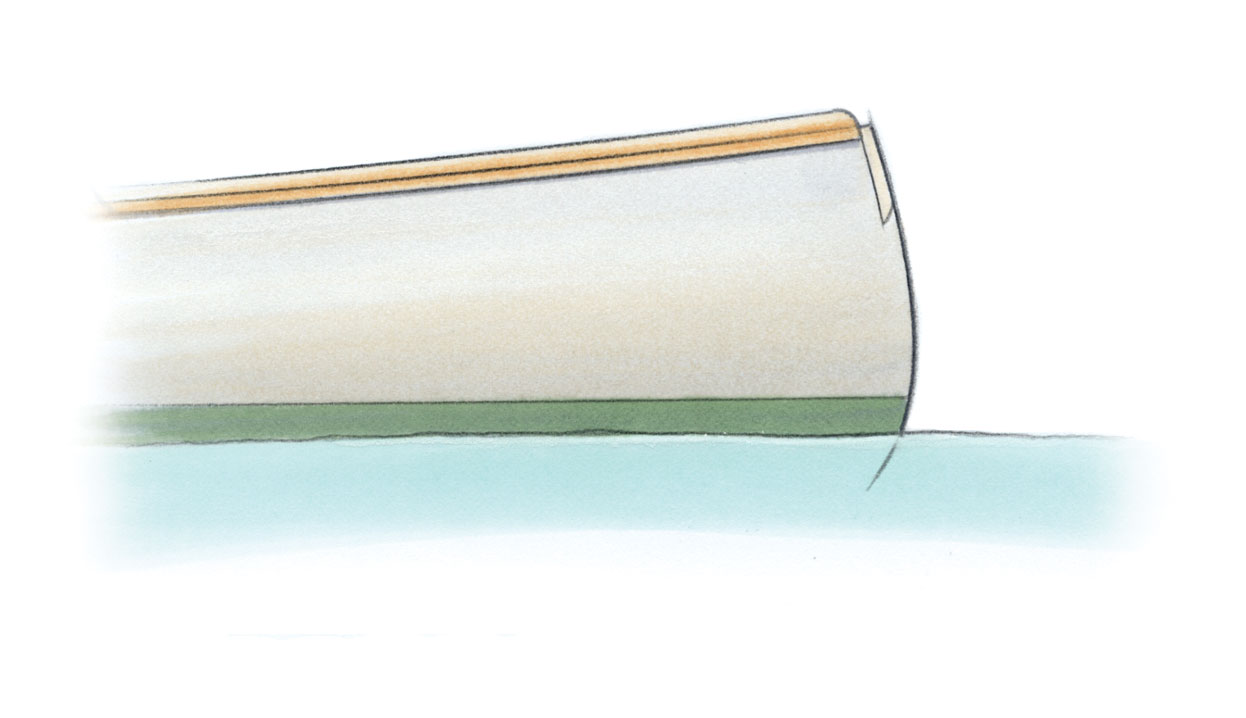

Round-bottomed Keel Sailboat

Adding a keel with built-in ballast to a round-bottomed boat adds complexity to the construction process. Also, if you look at the turn of the bilge (see cover illustration), you’ll notice that some of the planking has been hollowed out (“backed out”) in order to follow the round shape of the hull. Still, it’s easy to see that this shape would make a comfortable and stable boat, even in rolling seas. Whoever came up with the phrase, “Go with the flow,” might have sailed a round-bottomed sailboat. Its curved shape allows water to easily roll along its surface while its ballast keel acts as a pendulum and (usually) prevents the boat from tipping over while under sail.

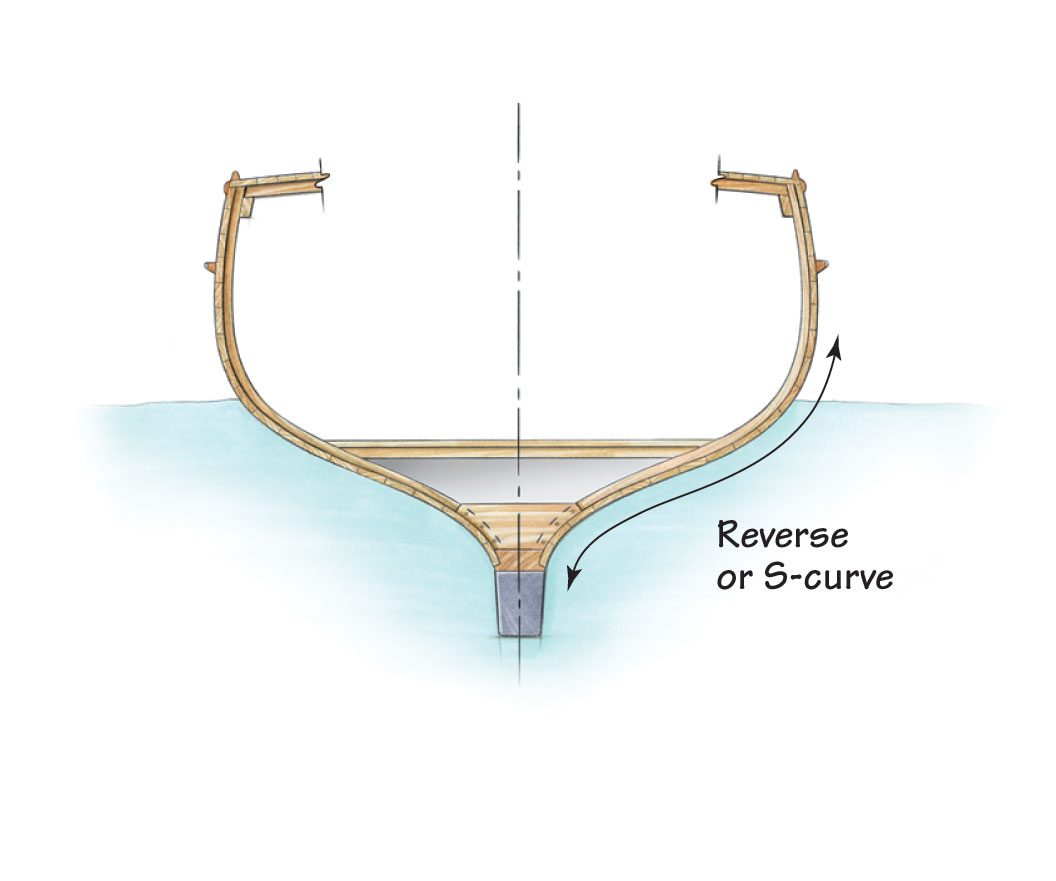

Reverse-curved Sailboat

This type of hull shape represents the toughest building challenge of all the boat shapes presented here. Notice the reverse (S) curves of the hull. The backbone and deadwood (keel area) and the planking, framing, and fitting out (adding interior elements) all require a higher degree of skill and workmanship. Add to that the fact that a sail, through its rigging, will be pulling on the structure over its lifespan. Yet, of all the shapes presented here, this one may be the most seakindly. The great weight of the ballast keel combined with the compound and complex curves of her hull shape allow the boat to take better advantage of breezes in both calm waters and heavier seas.

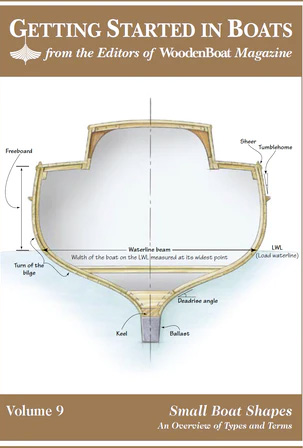

Small-Craft Stability

Naval architect C.W. Paine defined small-craft stability as “The propensity of the vessel to remain upright.” Two major types of stability apply to small boats: initial stability (how tender or not-tender a boat feels), and ultimate stability (the ability of a boat to return upright after being turned over). Because most small boats will remain inverted when turned over, initial stability is of primary interest to their users. On small boats, waterline beam (or the width of a boat at its LWL; see opening illustrations) is the principal factor in determining initial stability. A small increase in waterline beam can greatly increase initial stability. The shape of the sections also plays a part. For example, sections with good flare regain stability quickly when they are tipped, while slab or vertical sided boats do not.

Flare, Flam, and Tumblehome

Flare

Broadly defined, flare means to open or spread outward (think flare-legged blue-jeans). In terms of hull shape, I think a good definition comes from Ted Brewer’s book, Understanding Boat Design, 4th Edition. He says, “Flare is a concave section in the topsides.” When a motorboat increases its speed, flare allows its LWL (load water-line) beam to decrease quickly as it climbs out of the water to plane. As a boat with flare sinks down into the water, the LWL beam widens, giving added stability.

Flam

Again, I turned to Brewer for a definition: “Flam is a convex section in the topsides.” Slightly bulged in appearance, flam provides a hull with added buoyancy.

Tumblehome

Tumblehome is aptly named. It means that something (usually the side of a hull near the stern) tumbles (rolls) home (toward the center). In section, a hull with tumblehome appears wider within the lower or middle area of its topsides than it does at the sheer or deckline.

Other Characteristics That Affect Boat Shape

See also illustrations on cover and page 3

Sheer is easily seen in the side view of a boat. The sheerline is the topmost line of the planking, where the planking meets the deck (or the rails if the boat has no deck). It is the dominant line (of many) that determines the look of a boat.

Freeboard is the distance or height of the sides of the boat from the waterline to the sheer or deck line. Too little freeboard leads to easy entrance of water when the boat is heeled. Too much freeboard causes excess windage (as a wall to the wind) and weight of construction. It detracts from a boat’s appearance, too.

Topsides, sometimes confused with freeboard, is the surface area of the hull from the water-line to the sheer, or rail (the part that you see). Freeboard is always a distance; topsides is an area.

Rocker is the amount of fore-and-aft curvature to a boat’s underbody. The amount of rocker will help to determine how easily a boat will make turns. Too little rocker will render a boat that never wants to turn without a fight. Too much, and it will yaw (twist back and forth) and resist running on a straight course.

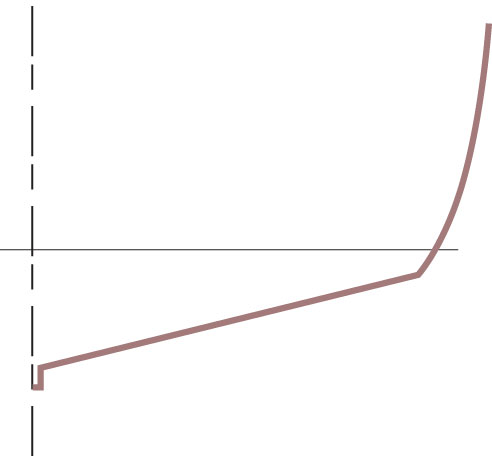

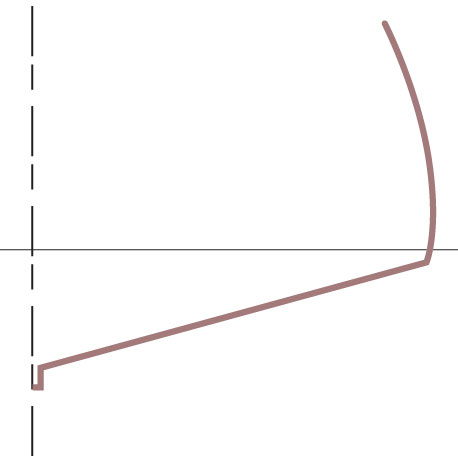

Deadrise angle describes the upwardness of the bottom (in section) from horizontal. On a flat-bottomed scow, skiff, or dory, deadrise angle is zero. On a V-bottomed powerboat, the deadrise angle may be as much as 20–25°, and even more on an extreme hull shape.

Overview of Bow Types

The Bow

At daybreak, there is hardly a prettier sight than watching a boat cut the first seam in flat water like sharp scissors cutting satin. Literally and figuratively, a boat makes a first impression with its bow.

Plumb Bow

The plumb (vertical) bow is an often-seen feature on wooden boats, especially older sailboats, launches, and other powerboats.

Raked Bow

The raked bow is the plumb bow tilted forward to give a sleeker appearance. It also adds room on deck (where applicable), shortens the boat’s waterline length, and can, because it accompanies flaring topsides, keep the boat drier when headed into a chop.

Spoon Bow

The spoon bow is the raked bow with curvature. It shares the same basic advantages and disadvantages as the raked bow. The majority of sailboats designed and built between 1900 and 1975 had spoon bows.

Bow with Tumblehome

Though a term usually applied to the hull’s sectional shape, tumblehome is also found in the bow profile of some catboats. This element accentuates the catboat’s already stylish look.

Transom Shapes

The Transom

As the bow makes a first impression, the transom makes a final, and lasting one. Here are some transom shapes that are common to small boats.

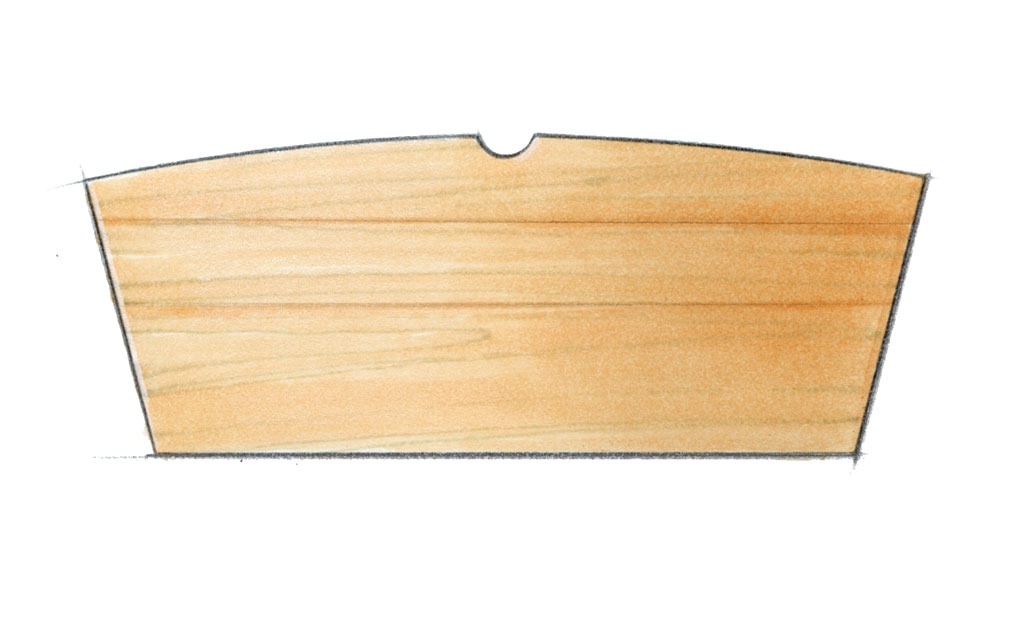

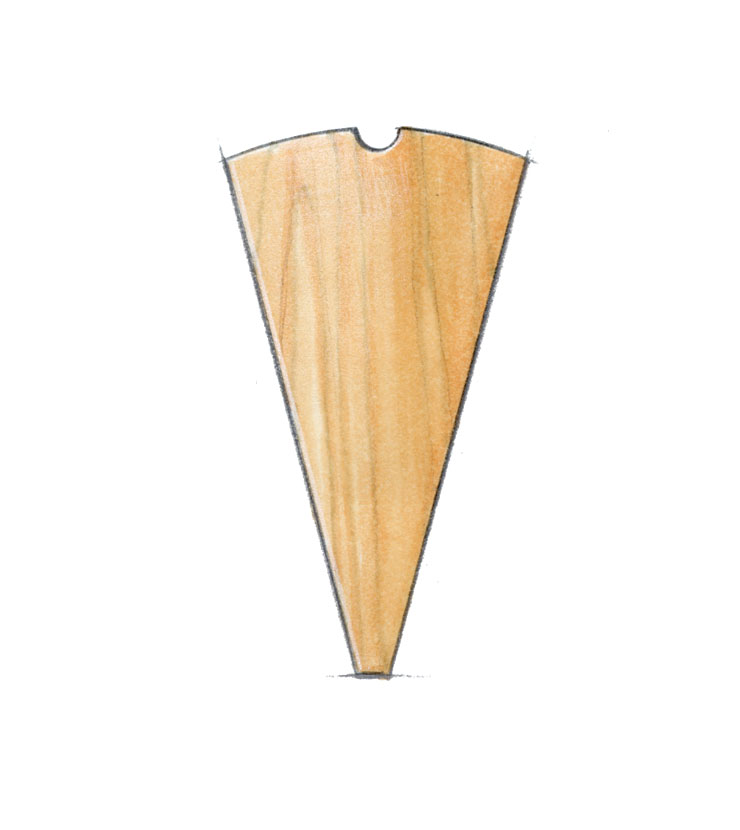

Skiff and Dory

The skiff transom is a slightly augmented trapezoidal shape—curved on top with beveled edges. This type of transom is easy to build from two or three hardwood boards with their grain running horizontally. When an outboard motor is not desired, most transoms of this type can be given some amount of rake (angle) that gives the boat a more attractive and slightly drier aft end. The dory transom is related to the skiff transom, though it is much narrower, rakes more, and is constructed with its grain running vertically. It has been dubbed a “tombstone” for its eerie similarity to that classic symbol of finality.

Round-bottomed

The round-bottomed transom is found on a wide variety of boats; most often it is seen on small, round-bottomed sailboats. It can be plumb or raked. While planking a round-bottomed boat can be more challenging than planking a skiff or dory, building its transom is no more difficult.

Wineglass Shape

The wineglass-shaped transom or a variation of it is found on Whitehall pulling boats and sometimes on sailboats. It is often chosen for its beauty alone, but occasionally is also used when the designer wants a double-ended waterline (one that’s pointed at both ends, similar to a canoe when viewed from underwater).

In many ways, each boat is as unique as her designer or builder. We have covered only a few of the most common forms here. Still, having a basic understanding of these small-boat shapes, we hope, will enable you to look at all boats in a new light. Depending upon your boat’s intended use, you’ll be able to use this guide to choose the characteristics that best serve your purpose. Then, as you look at boat plans, you’ll recognize more of these telling features and be able to proceed with confidence as you decide upon your first (or next) boatbuilding project.

Karen Wales is WoodenBoat’s Associate Editor. Further Reading Understanding Boat Design, 4th Edition, Ted Brewer. The Boatbuilder’s Apprentice, Greg Rössel. Boatbuilding Manual, Fourth Edition, Robert M. Steward. (All titles are available at The WoodenBoat Store. <www.woodenboatstore.com>.)