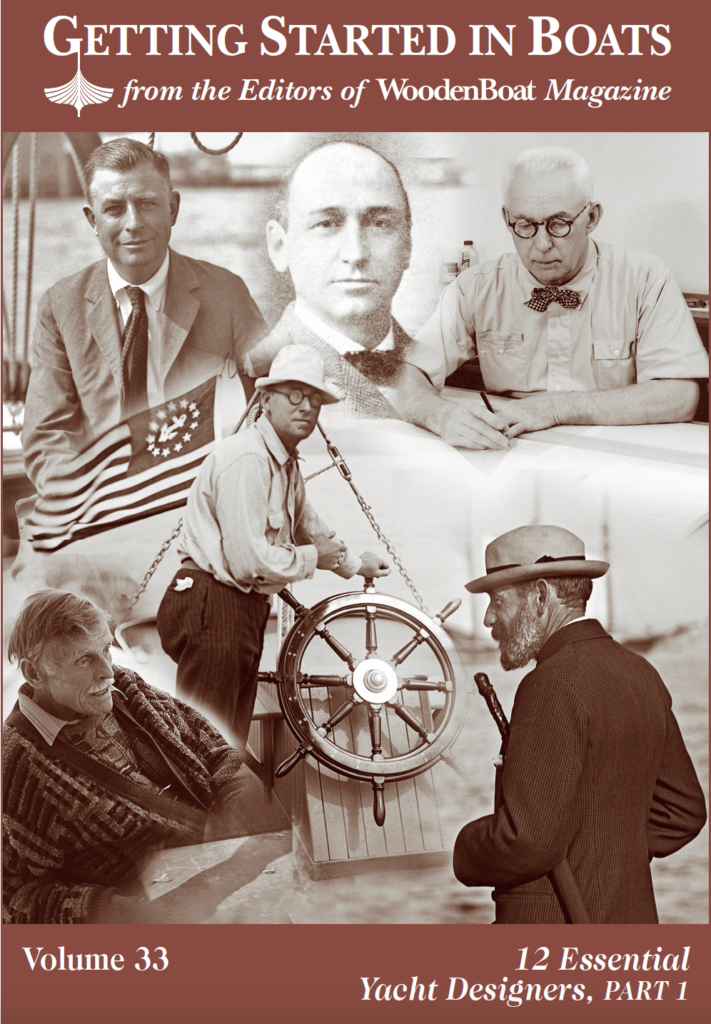

Alden • Atkin • Crowninshield • Garden • Hand • Herreshoff

As one develops an appreciation of yacht design, one runs into certain designers’ names again and again. The purpose of this article is to introduce 12 important 20th-century designers and to tell just enough about each one to describe the overall arc of his career. The editors picked a dozen as the number, and we agreed on what we think is a well-rounded group of often-heard names that we hope will benefit the reader who is just starting to appreciate the art and science of yacht design. Six of these designers are portrayed in this issue of Getting Started in Boats, and six more will be presented in the next issue. We don’t mean to say these 12 are “the best of all” designers, although they are certainly among the best of all time, nor is this presentation considered a ranking.

In this issue, our subjects are John G. Alden, William Atkin, Bowdoin Bradlee Crowninshield, William Garden, William Hand, and Nathanael Greene Herreshoff. In Part 2, to appear in WoodenBoat No. 226, the subjects will be Olin Stephens, Philip Leonard Rhodes, Charles Raymond Hunt, W. Starling Burgess, William Fife III, and Leslie Edward “Ted” Geary.

It is the designer’s job to create a boat for a particular individual, pattern of use, or locality. Few objects are created through such a dynamic interplay of science, natural evolution, tradition, and art. One yacht may be judged against another in any of a number of ways depending on the observer’s priorities, such as beauty, construction technology, comfort, or speed, but every yacht must function in harmony with the eternal natural forces of wind and waves in her given locality or across the oceans of the world. There is no escaping the connection between boats and nature, and that may be part of the reason why they seem to affect us on a deeper level than most of the other objects in our lives.

Those who wish to seek a deeper understanding of these yacht designers and yacht design in general will find a solid technical and historical foundation in these books: Skene’s Elements of Yacht Design by Francis Kinney; The Encyclopedia of Yacht Designers, which I edited with Lucia Del Sol Knight; Understanding Boat Design by Edward S. Brewer; and Yacht Designing and Planning by Howard I. Chapelle. Further reading about these designers and their work can be found in numerous WoodenBoat magazine articles (see the online index at the “Research” tab at WoodenBoat.com) or in biographies written about the designers, or in many cases in books written by the designers themselves. The books listed above and those listed at the end of each segment in Parts 1 and 2 are available through The WoodenBoat Store.

John G. Alden

1884–1962, Boston, Massachusetts

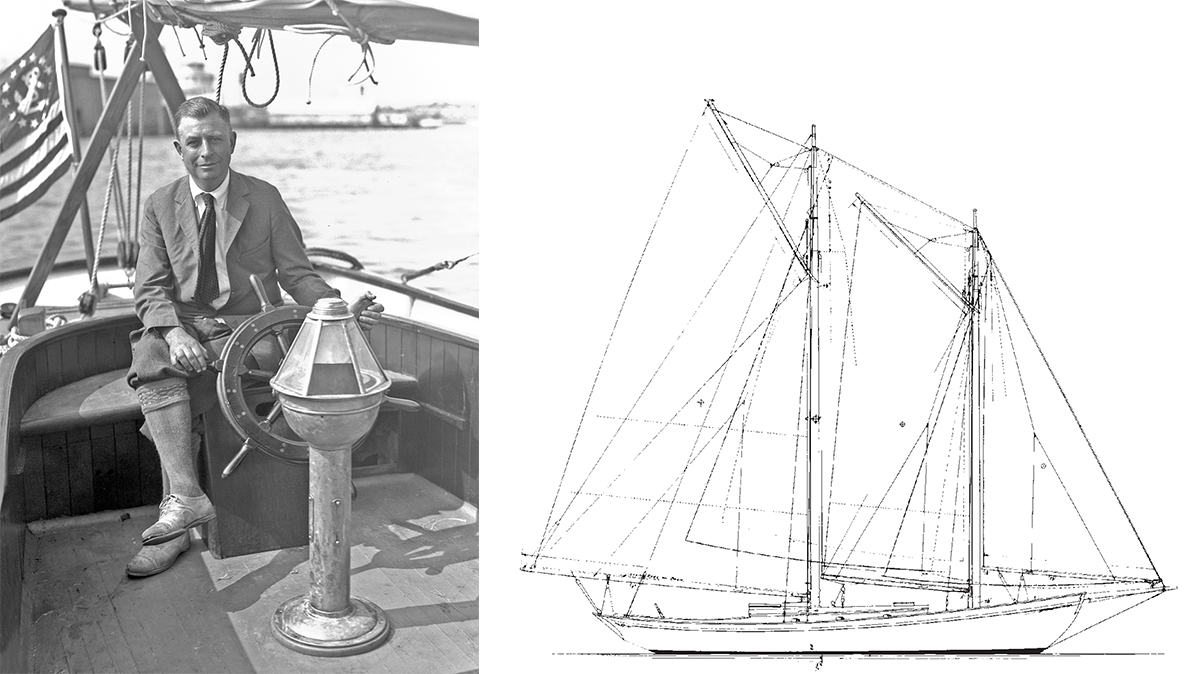

John G. Alden, shown above during the 1925 Bermuda Race, designed thirteen yachts named MALABAR—ten of them schooners—for his personal use. At right is MALABAR II of 1922. One of Alden’s most admired designs, she is still sailing today, and her plans are available from the WoodenBoat store.

John Alden began his independent career in 1909 after apprenticing with W. Starling Burgess and B.B. Crowninshield. Early on, he gained a widespread reputation for small schooners that he had based on fishing boats operating out of Gloucester, which were well suited for the then-new sport of ocean racing. It was one of the few times in history when successful racing yachts were also superb cruising yachts, and because of this versatility many Alden schooners have been preserved. Alden himself raced ten schooners named MALABAR that he had designed and had built for himself to test hulls, rigs, details, and aesthetics. His MALABARs won the Bermuda Races of 1923 and 1926, and in 1932 the first four places were taken by Alden schooners. (Three of Alden’s personal MALABARs after MALABAR X were not schooners; one was a yawl and two were ketches.) Alden’s office produced about 150 schooner designs in all, and a series of 43-footers are considered among the most beautiful and seamanlike cruising boats ever drawn.

Racing rules—complex formulas that involve a complicated set of measurements—have often influenced yacht designs. A racing rule developed by the Cruising Club of America (CCA) in the 1930s encouraged yawls and sloops of more modern hull form and using marconi rigs—so called because the triangular sails were set on masts tall enough to remind people of inventor Guglielmo Marconi’s radio transmission towers. Alden designed some of the finest examples of the new type as well. These, too, combined capabilities for both racing and cruising, establishing harmonious aesthetics that became more or less permanent standards.

Besides schooners and ocean racers, 44 motorsailers, and 88 power yachts, the Alden office produced many racing sloops, cruising sloops, yawls, and ketches, including such semi-production family cruising-boat designs as the Coastwise Cruiser, Barnacle, Malabar Senior, and several variations of the Malabar Junior design. In all, 106 “one-designs,” or boats built identically for racing against each other, were produced, including the Biddeford Pool One-Design, the Alden O-boat, the Alden Triangle, the Indian class, Sakonnet, and U.S. One-Design.

(A profile of Alden appeared in WoodenBoat No. 32; see also John G. Alden and His Yacht Designs, by Robert W. Carrick and Richard Henderson. Alden’s plans reside with Niels Helleberg Yacht Design, the successor to Alden’s company; see www.aldendesigns.com.

William Atkin

1882–1962, New York and Connecticut

William Atkin designed a wide variety of boats, among them Scandinavian-inspired double-enders like the 32’ cutter DRAGON shown above. Atkin had a prolific career as a designer and yachting writer, first on his own and later with his son, John.

Some designers achieve fame on the race course or with technological innovation, but others are appreciated because their work finds an emotional connection with everyday people, generation after generation. William Atkin seldom designed racing boats but drew boats for about every other conceivable purpose. He was as good a writer as he was a designer. In addition to three books, he is known for the designs he published in the MotorBoating “Ideal” series. He was the editor of Yachting during World War I, technical editor of Motor Boat after that, and edited his own magazine, Fore An’ Aft, from 1926 to 1929. Beyond the usual technical information, much of his writing served to point out what was enjoyable about each design and what type of person would get the most out of it.

Atkin was one of the first designers to introduce American yachtsmen to heavy-displacement, double-ended offshore cruising yachts based on Scandinavian antecedents. Such boats, some later built in fiberglass, helped popularize offshore sailing after World War II. Beyond this, however, his work includes a wide variety of large and small sailboats, a large number of powerboats, many small craft for a wide range of purposes, and a number of much-beloved houseboats and shanty boats. The fundamental excellence of his small boats is once more being discovered and appreciated today.

Atkin’s career eventually merged with that of his son, John, who continued and greatly expanded upon the traditions his father established.

(A profile of the Atkins appeared in WoodenBoat No. 168–169; see also The Book of Boats Volumes I and II, Three Little Cruising Yachts, Motor Boats, and Of Yachts and Men. Atkin’s plans reside with Pat Atkins; see www.atkinboatplans.com.)

Bowdoin Bradlee Crowninshield

1867–1948, Boston, Massachusetts

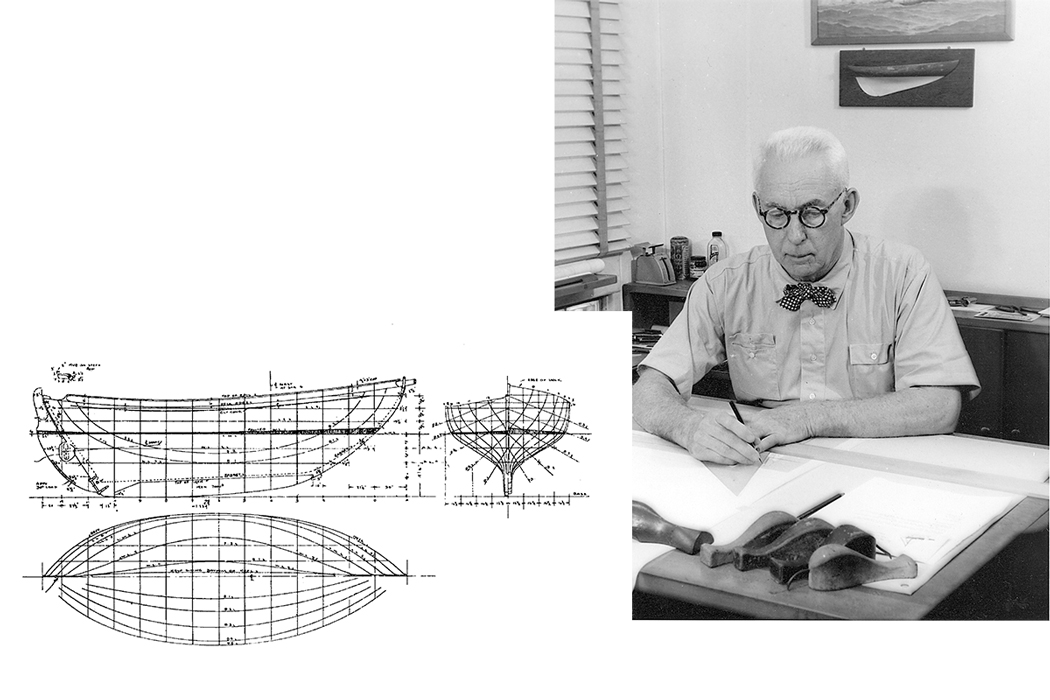

At a time when many designers were taking inspiration from successful workboats, B.B. Crowninshield introduced ideas specific to yachts. His Dark Harbor 121/2, shown here (and available from the WoodenBoat Store) is one of his classic small daysailers.

A major figure in racing yacht design in the early 20th century, B.B. Crowninshield was among the first to move firmly toward a pure “yacht” style of hull that bore little resemblance to earlier commercial types. A typical Crowninshield yacht is long-ended, narrow, and deep, with entirely outside ballast on a very abbreviated, fin-like keel; U-shaped ’midship sections; and a large rig. They ranged in size from the Dark Harbor 121/2 (12′ 6″ on the waterline) to the 90′ extreme AMERICA’s Cup defense candidate INDEPENDENCE. Yachts of this form were optimized for smooth water and the relatively light airs of summertime, and they were created before ocean racing and voyaging, family cruising, and living aboard came to require entirely different hull shapes. Crowninshield’s cruising yachts tended toward the same general proportions as his racers. In his time auxiliary engines were uncommon, so sailing performance in a wide range of conditions, including light wind, was important in a way it is not for most yachtsmen today.

One of Crowninshield’s major contributions was in refining Gloucester fishing schooners to be safer and faster, adapting yacht-like characteristics (especially deep draft and more Vshaped sections) to offshore commercial use. In an interesting twist, Crowninshield’s apprentice John Alden was later instrumental in adapting the Gloucester schooner type for yachting.

Few Crowninshield yachts survive today because of their extreme forms. They were too flexible to last very long without strengthening, and in general the type of hull went out of style. Nevertheless, Crowninshield designs are some of the most beautiful examples of the type, and the few boats built from them that do survive are much valued in classic yachting circles.

(Crowninshield’s plans reside at The Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts; see www.pem.org.)

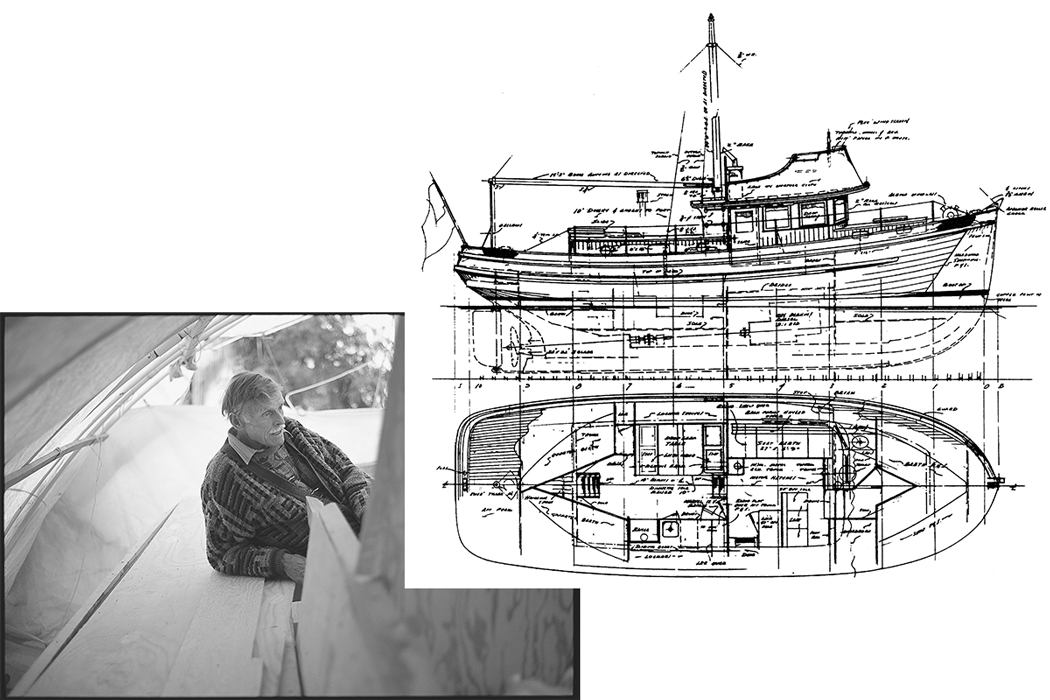

William Garden

1918–2011, Seattle, Washington and Sidney, British Columbia

William Garden designed workboats and pleasure boats of all kinds. The powerboat shown here is a 37’ LOA troller yacht distinctly showing her commercial fishing boat heritage.

Remarkably versatile, William Garden produced sailing yachts, power yachts, military craft, towing boats, cargo carriers, small craft, fishing boats—over 1,000 designs—in what may have been the longest career of any designer. He could produce a design that was strictly traditional, and he had direct, detailed knowledge of such types. He also designed many boats that were purely futuristic, boldly advancing into new territory. Most often his designs were best described as “timeless,” being contemporary in most respects but showing a sweetness of line that nonetheless connected them to traditional aesthetics. Fishing boats for the Pacific Northwest and motoryachts that resembled them were a big part of Garden’s output, and he clearly enjoyed yachts with a rugged, no-nonsense workboat sensibility.

Coming as he did from a temperate coast with a lot of rain, Garden often worked pilothouses into his sailboat designs, making them ideal for year-round use. He also designed sailing craft for commercial fishing and cargo-carrying.

While many of Garden’s power cruisers were of the heavy-displacement, low-speed fishingboat- inspired type he helped to popularize, he also drew a considerable number of larger, luxurious motoryachts with modernistic lines but having seamanlike features. He created a large number of charming cruising yachts, some of them very small. Remarkably, considering his penchant for heavy displacement, he occasionally drew excellent light-displacement cruising sailboats that show the potential of the type when it is uninfluenced by racing handicap rules.

(Garden wrote Yacht Designs, Volumes I and II; The Making of Tom Cat; and numerous articles in WoodenBoat. A boat built to one of his designs appears on page 64 of the current issue. His plans reside at Mystic Seaport; see www.mysticseaport.org.)

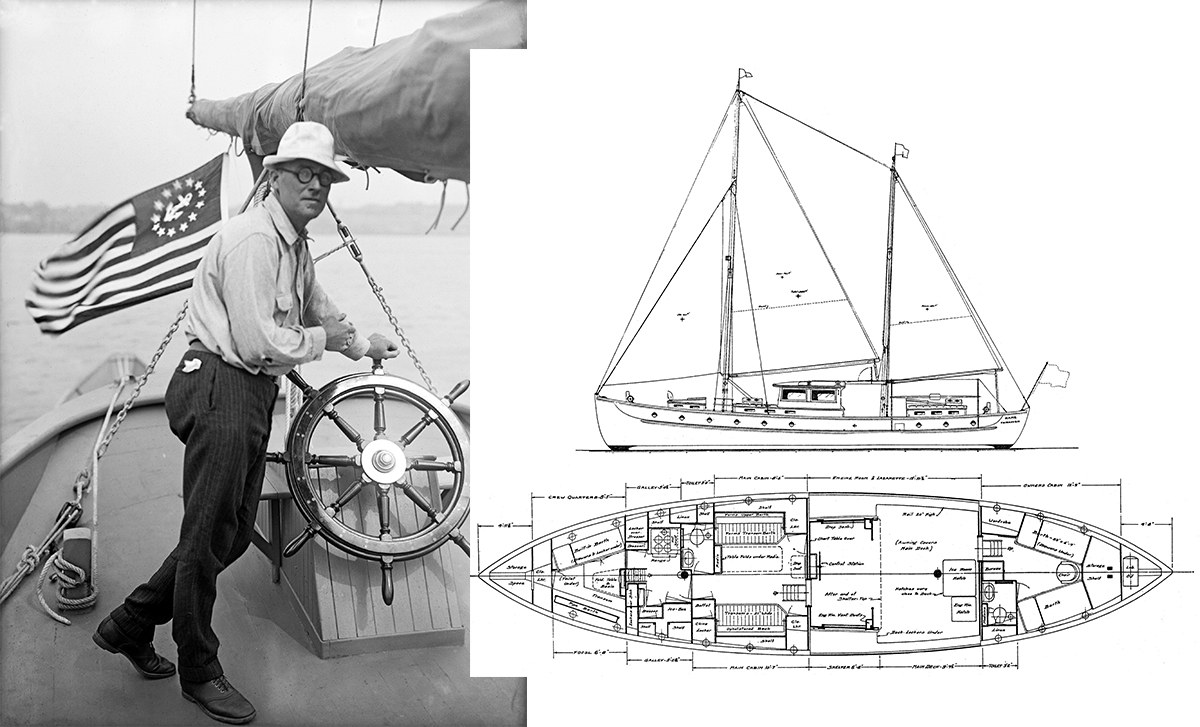

William Hand

1875–1946, New Bedford, Massachusetts

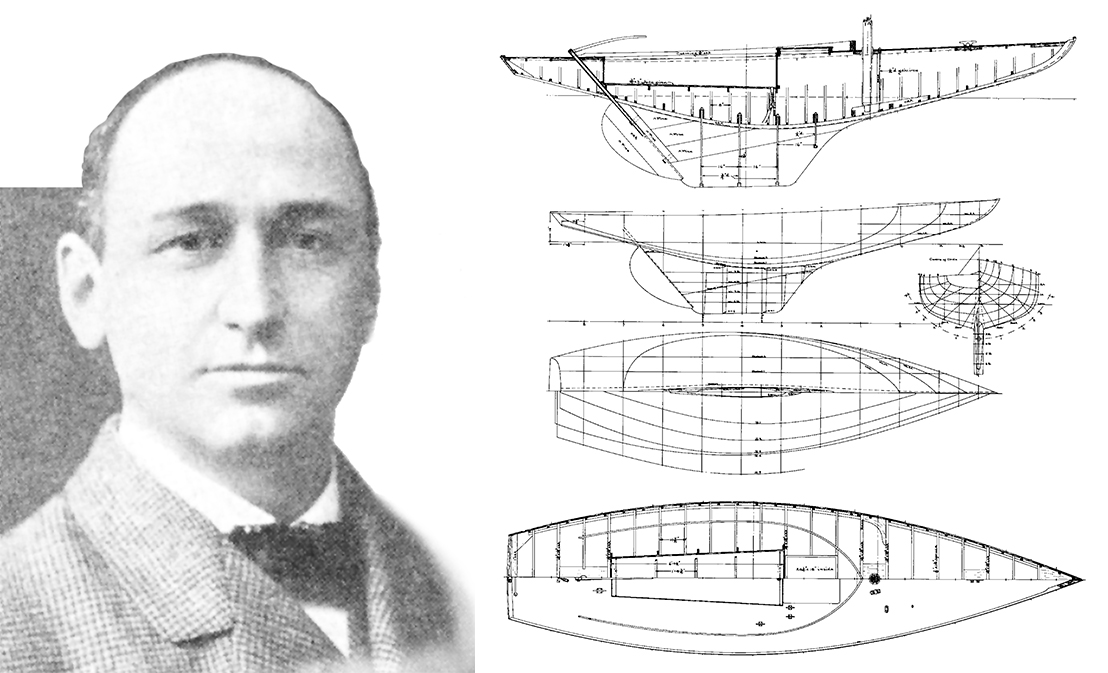

William Hand, shown above in 1923, made the design of cruising motorsailers a specialty. The 63’ double-ender shown here came off his design board in 1933, and one of the two sisters built that year was for Hand’s personal use.

Another very versatile designer, William Hand is primarily known today for his motor- sailers, which are regarded as some of the best of that genre. A motorsailer is primarily a motorboat but has a sailing rig capable of being the yacht’s sole propulsion in winds over about 18 knots, and serving to reduce motion, ease steering, and increase fuel economy whenever desired. Large tankage provided good range under power, with 1,500 miles being typical. While most of Hand’s motorsailers were built to high yacht finish, they retain a seriousness of appearance derived from their commercial ancestors, most notably the Maine sardine carrier. Hand’s superstructures always included a pilothouse, but in size they fall about midway between those typical of a sailboat and those commonly seen on powerboats, contributing to an interesting and refined appearance. Some of his motorsailers, including those he had built for himself, were used for swordfishing, with the addition of the necessary bowsprit platform for the harpooner.

Schooners were another of Hand’s important contributions, and while they were often successful on the race course they were somewhat more rugged, dramatic, and workboat-like in appearance than their contemporaries. Hand’s bestknown schooner is the 88′ BOWDOIN, drawn in 1921, which made many voyages of exploration to the Arctic and continues to do so today under the ownership of the Maine Maritime Academy.

Hand was among the first to adapt the Chesapeake deadrise-type workboat form to produce fast, handsome V bottomed motorboats, including some early speed-record holders.

(A profile of Hand appeared in WoodenBoat Nos. 28–29; see also Designs of William Hand, Jr., compiled by the WoodenBoat Research Library. Hand’s surviving plans reside at The Hart Nautical Collections, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge; see web.mit.edu/museum/collections/nautical.html.)

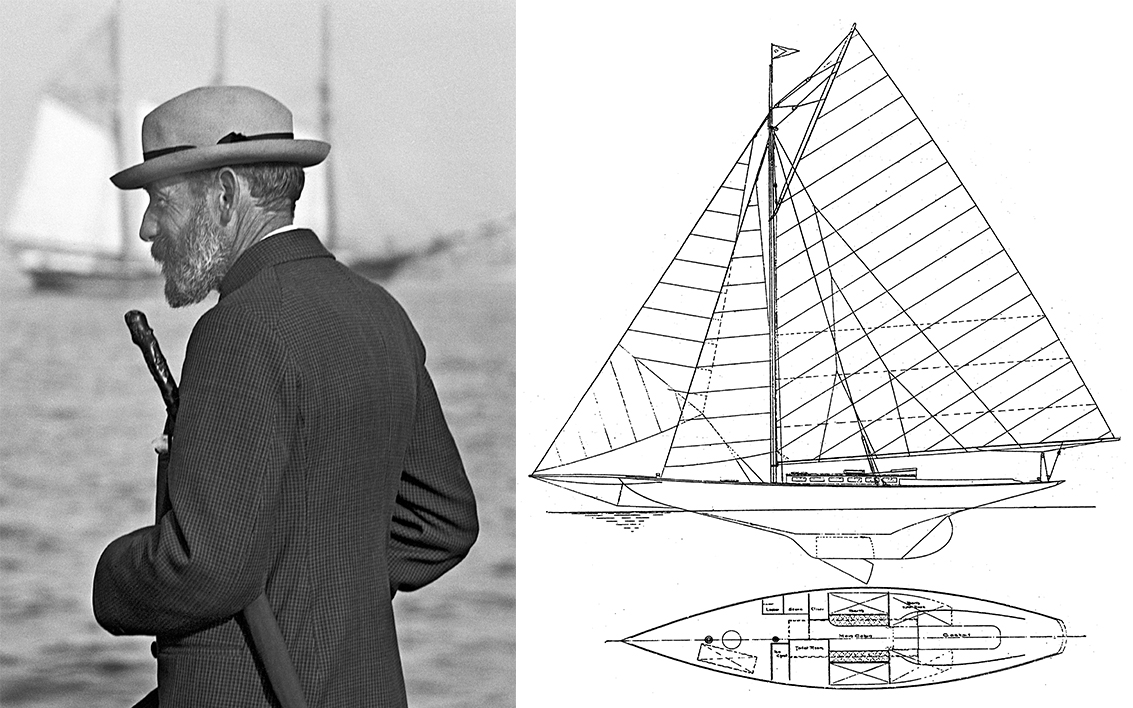

Nathanael Greene Herreshoff

1848–1938, Bristol, Rhode Island

Fourteen Buzzards Bay 30s, 30’ on the waterline and 46’6” overall, were built for the 1902 racing season at the Beverly Yacht Club in Massachusetts to a design by N.G. Herreshoff (shown above in 1894). Four of the surviving sisters were fully restored in 2008; see WoodenBoat No. 203.

Few would dispute that N.G. Herreshoff is the most gifted and successful yacht designer the world has produced so far. A structural and mechanical engineer of great genius, he designed the boilers and engines for the steam yachts and military vessels he designed, and he created sailing yachts that were lighter, stronger, and faster than those of his competitors. Herreshoff boats have an unusually high survival rate, and many still sail either in original condition or after having been restored to original condition.

He invented hardware still in use today, including sail tracks and slides, and he improved the designs of winches, anchors, and cleats. He also helped popularize the use of fin keels, bulb-shaped ballast keels, spade rudders, folding propellers, hollow wooden spars, and metal spars. He is believed to be the first American to develop a practical fast catamaran. He also pioneered efficient semi-production boatbuilding methods at Herreshoff Mfg. Co.

His AMERICA’s Cup defenders were VIGILANT (1893), DEFENDER (1895), COLUMBIA (1899 and 1901), RELIANCE (1903), and RESOLUTE (1920). Some of the most wholesome and beautiful, as well as fastest, racing yachts ever created under a rating rule were designed under the Universal Rule, which he devised around 1904. He himself designed many of the finest yachts built to that rule, in various classes always designated by letters, such as J, P, Q, and R. He also designed a large number of one-design classes, including the New York 30, 40, 50, 65, and 70; the Buzzards Bay 15, 25, and 30; the Bar Harbor 31; the Newport 29 and 30; the Fish class; and the immortal Herreshoff 121/2, nearly 400 of which were built.

N.G. Herreshoff’s son L. Francis Herreshoff was also a gifted designer and a much-beloved yachting writer. Another son, A. Sidney DeWolf Herreshoff, served as chief designer at the Herres-hoff Mfg. Co. in its later years. Halsey Herreshoff, son of Sidney, continues the Herreshoff tradition today at Herreshoff Designs, Inc., www.herreshoffdesigns.com.

(A profile of Herreshoff appeared in WB No. 33–35. See also Capt. Nat Herreshoff by L. Francis Herreshoff; Herreshoff of Bristol, by Maynard Bray and Carlton Pinheiro; Recollections of N.G. Herreshoff by N.G. Herreshoff; and Herreshoff and His Yachts by Franco Pace. The designer’s half models reside at the Herreshoff Marine Museum in Bristol, Rhode Island; see www.herreshoff.org. Plans and specifications reside at The Hart Nautical Collections, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Museum, Cambridge; see web.mit.edu/museum/collections/nautical/html.)

Dan MacNaughton is co-editor, with Lucia Del Sol Knight, of The Encyclopedia of Yacht Designers. He currently works as a finisher at Artisan Boatworks in Rockport, Maine, and is a frequent contributor to WoodenBoat.