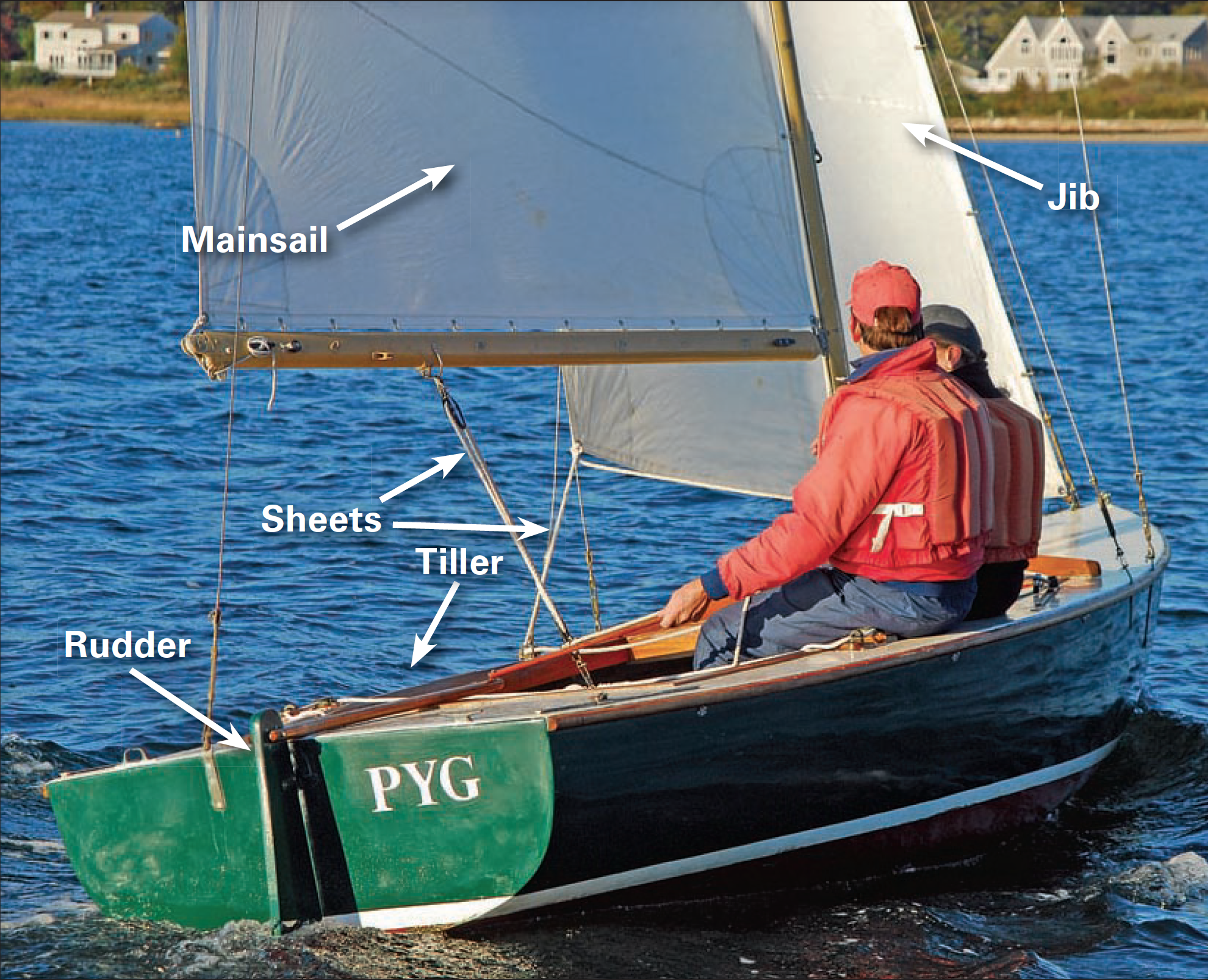

Above-This boat is on a starboard tack, as the wind is coming over the starboard side. In this case, the starboard side is the windward side of the boat and the port side is the leeward side. Notice that both skipper and crew wear U.S. Coast Guard approved personal flotation devices (PFDs), a very smart practice.

Learn the Basics of How to Sail

There’s nothing finer than spending a sunny summer afternoon under sail. Learning how to sail can be broken down into a handful of basic concepts. This includes sailing in a straight line, relative wind angle (RWA) and the points of sail, appropriate sail trim, turning your boat upwind (tacking), and turning your boat downwind (jibing). In this article, we’ll take a close look at the basics, using a Rhodes 18 sloop. While you may need to make a few adjustments when you use a different boat, the principles given here will remain the same.

There is no better way to learn sailing than to practice. The elements described here should give you a good start.

Heading down (left)—As the tiller is pulled to windward, the bow of the boat is directed away from the wind. This action is called heading down. Heading up (right)—As the tiller is pushed to leeward, the bow of the boat is directed toward the wind. This is called heading up.

Sailing Terminology

Here are some common terms you’ll hear aboard a sailboat:

Centerboard: Prevents side-slipping when sailing toward the wind

Heading Down: If you steer the bow away from the wind, or downwind, on an increasing RWA, you are heading down.

Heading Up: If you turn the bow toward the wind, or upwind, so that the RWA decreases, you are heading up.

In Irons: A boat is in irons if the bow is facing directly into the wind and the sail luffs (flaps)

Jib: The sail forward of the mast

Leeward: The downwind side of the boat is the leeward side.

Mainsail: The sail aft of the mast.

Port or Starboard Tack: Indicated by the side of the boat facing the wind. A boat on a starboard tack has the wind coming over the starboard (right) side, which means that the boom is on the port (left) side.

Relative Wind Angle (RWA): Angle of the wind, relative to the boat as the crew faces forward

Rudder: The vertically hinged plate near the stern that steers the boat.

Sheets: The lines (ropes) used to trim the sail in or ease it out

Tiller: Controls the rudder and provides leverage for steering.

Windward: The side of the boat that the wind hits first is the windward side.

Above-Telltales stream back with the wind and are one of many good ways to indicate relative wind direction.

Wind Direction

The key to understanding the dynamics of sailing is to develop a feel for wind direction. If you know the wind direction, you can set your sails accordingly and steer your boat to a chosen destination. You can determine the wind direction using a number of methods: You can observe how boats on moorings or at anchor are pointing (barring a strong current, they face into the wind, if there is any); you can see how flags, pennants, and telltales (yarn, string, or the like tied to your shrouds) stream away from the wind; you can also find the direction of wind by watching its effect on the surface of the water (ripples), and by the waves generated and directed by the wind.

Remember that wind direction is named by the direction it comes from—northeast, southwest, etc—not the direction it is blowing toward.

Relative Wind Direction

Based on the wind direction, you can direct the boat by steering at a relative wind angle (RWA) from the wind. I find that using telltales (I like to use ribbons of old cassette tape) on the port and starboard shrouds is invaluable in showing the angle of the wind relative to the boat. Sailors distill these RWAs into three sectors called points of sail: close-hauled, reaching, and running.

Points of Sail

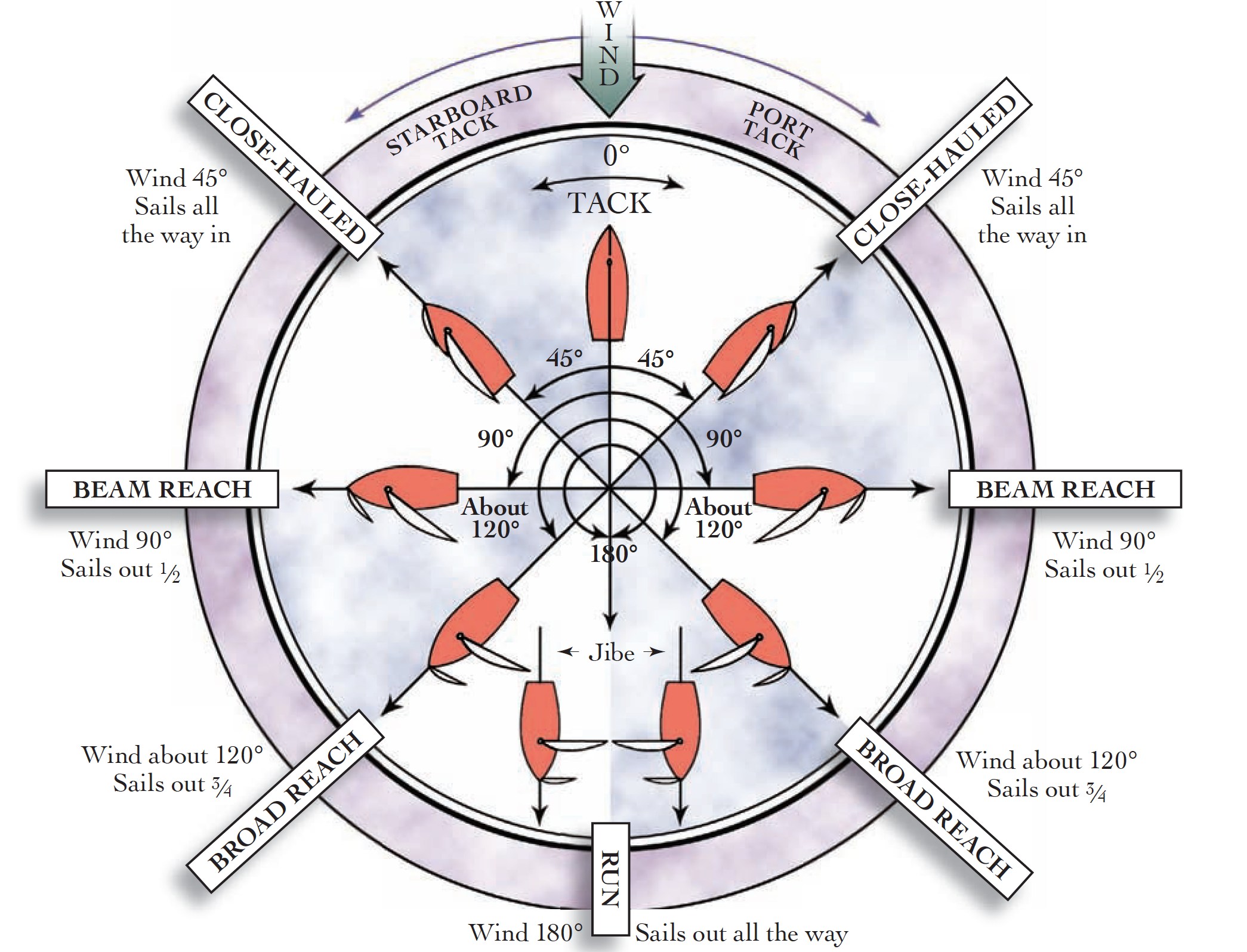

Now that you have some understanding of terms and conventions, you’re ready to grasp the points of sail. For every point of sail, there is an appropriate sail position. Think of your sails as engines that propel the boat forward.

The chart above depicts the various points of sail. It’s a good idea to keep a laminated copy of a chart like this on board.

Close Hauled—The boat is sailed as close to the wind as possible (45° RWA) with the sails sheeted in as close to the centerline of the boat as is practical.

Close-Hauled

A close-hauled point of sail is when the RWA is approximately 45° (the exact RWA is dependent on the boat’s design). If you are close-hauled, you are pointing the bow of the boat as close as possible to the wind without the sails luffing. (Too close, and the sails will lose their shape and flap like a flag on a flagpole; this flapping is called luffing.)

Some sailors refer to sailing close-hauled as “threading the needle” or being “in the groove.” In order for a sailboat to reach an upwind destination, the sailor must direct the boat by zigzagging (tacking) at 45° RWA. The correct sail trim for being close-hauled is to sheet the sails all the way into the centerline of the boat, or to trim in as close to this position as practical.

Beam Reach—The RWA of the boat to the wind is 90° and the sails are eased out about halfway.

Reaching

The reaching point of sail means the bow of the boat points farther away from the wind than close-hauled and creates a relative wind angle between 60° and 120°. For this point of sail, you ease the sails out. Reaching is subdivided into close-reaching (RWA 60°, sails out one-quarter), beam-reaching (RWA 90°, sails out one half), and broad-reaching (RWA 120°, sails out three-quarters). When the boat is steered to a reaching position, the sails are eased until they luff slightly and then trimmed in until the luffing stops.

Running

A running point of sail is when you head down and the wind comes more or less directly over the stern (RWA 180°). For this, the sails are extended out as far as they will go and as close to perpendicular to the boat’s centerline as practical. While running, the wind is pushing from behind.

It is critical to lower the centerboard for sailing close-hauled, close-reaching, and beam-reaching, for this prevents the boat from side-slipping. When running, the centerboard may be raised.

Tacking

In order for your boat to sail to a destination that is directly upwind, you have to alternate from one close-hauled tack to another (starboard tack to port tack or vice versa). This upwind maneuver is called tacking.

You should inform your crew that you are about to tack by calling out “Ready to come about.” The crew responds “ready,” then the skipper says “hard a-lee.”

The mainsheet remains tightly trimmed to centerline, while the tiller is pushed toward the sail (or to leeward). You should always face forward and pass the tiller behind your back as you tack so you can see how quickly you are turning the bow of the boat. Remember that if you linger while headed directly into the wind, the sails and boat will stall, and you will gradually lose steerageway and be caught in irons. Also, if you put the helm too far over, you might stall the boat.

Once you have completed the tack and have the boat headed toward the new 45° RWA, be certain to center the tiller appropriately and direct the boat straight on its new course.

Tacking Maneuver in Four Steps

1. With the boat close hauled, the skipper heads the boat up, turning the bow of the boat into the wind.

2. The sails luff as the relative wind angle decreases. The crew changes jib sheets as the jib shifts from one side to the other.

3. On the new close-hauled position (port tack now) the skipper moves to the new windward (port) side of the boat. Inset—The boat will remain “in irons,” with the sails luffing, eventually losing forward momentum if the bow of the boat is not directed entirely through the tack.

4. The boat and crew assume the new close-hauled position (RWA 45°).

Jibing

When you are running directly before the wind with the sails all the way out and you turn the stern through the wind from one downwind tack to the other, you are jibing.

The mainsail works on either side because the wind is pushing from behind (180° RWA). This is when an unexpected jibe can happen and be potentially dangerous. The mainsail and boom can shift across the stern from one full-out position to the other very rapidly, potentially causing damage along the way.

Before you jibe, size up in advance where the bow should be pointing for the new RWA. Announce to your crew: “Prepare to jibe!” It is best to control the jibe by hauling in the mainsheet before turning the stern through the wind. The helmsman should move the tiller away from the sail to jibe and keep looking forward as in tacking, visually tracking the turn.

After the mainsheet is all the way in but before the boom comes across the stern, the helmsman should shout, “Jibe ho!” Once the turn is completed to the new downwind RWA of about 150°, you can slowly ease the mainsail all the way out.

Tip: The mainsail and the boat will be more stable and you will prevent accidental jibes if, when sailing downwind, you steer the boat on a broad reach (RWA 160°). This will clearly keep the sail on one side of the boat and prevent the jibe.

Jibing in Five Steps

1. Before the jibe, the boat is established on a run.

2. As the skipper heads the boat farther downwind, the stern crosses the wind, and…

3. …the sails slam over to the new leeward side (starboard in this case). Pulling in the main sheet makes the maneuver less violent. The crew shifts the jib sheets.

4. The skipper moves to the new windward side.

5. The jibe is complete when the boat is now on the opposite tack and is running before the wind with the sails again eased out.

Left—In a small boat the helmsman steers the boat with the tiller in one hand and the mainsheet in the other, always ready to quickly slack the sheet for a sudden puff of wind. Right—In a jibe or a tack, the crew switches the jibsheet from the old leeward side to the new as the relative wind position changes.

Some Fine Points

If your boat is a sloop, like our Rhodes 18, and the jib has two sheets, you will have to shift the jibsheets from one side to the other with each new tack. The leeward jibsheet will be under tension and the windward sheet will always be “lazy” or slacked off. When the mainsail comes over during a tack and jibe, the jib will want to do the same, so to allow this, you have to let go one of its sheets and haul in the other.

If you apply these simple elements, you can sail any small boat. By controlling your boat’s direction and sheeting its sails to the wind direction, you can deftly sail your boat.

There are a lot of good avenues for becoming a better sailor. Sailing courses abound in nearly every part of the world. Many sailors have room on their boats for one more enthusiastic hand. After giving this article careful study, try networking in your area. Soon you’ll be ready to strike out on your own!

Capt. Dave Bill is a sailing instructor at WoodenBoat School and chairman of the Nautical Science Department at Tabor Academy in Marion, Massachusetts. For more of Capt. Dave’s stories and sea wisdom, go to BoatsandLife.com.

Further Reading

The Complete Sailor: Learning the Art of Sailing, by David Seidman (Copyright 1994, 1995 International Marine, Camden, Maine)

The Craft of Sail, by Jan Adkins (Walker and Company, Inc., New York, New York)

Sailing for Everyone, by Simon Watts (Pelikan Press, WoodenBoat Books, Brooklin, Maine 2008)