Learn to Drive a Boat With a Motor

Driving a powerboat, especially in close quarters, is an often misunderstood process one fraught with potential embarrassment as dockside onlookers scrutinize your maneuvering.

An understanding of the basic forces acting on a powerboat, and how to use those forces to your advantage, is all it takes to dock and undock with confidence. If you’re new to powerboats, or if you’ve been around them for a while but are not confident at handling them, the following drivers’ education is for you. We’ll focus on the basics here: single-engine, single-propeller boats—both inboards and outboards*—leaving twin propellers and bow thrusters for your own further exploration.

Study the following steps, practice them carefully, and you’ll soon have an intuitive understanding of powerboat handling. Do your practicing away from an audience, since distraction and self-consciousness will only hinder the learning process.

*All discussions of outboard-motor handling also apply to inboard-outboard, or sterndrive boats, as the handling qualities of these two propulsion systems are, for the most part, identical (except that the counter-rotating sterndrives handle better).

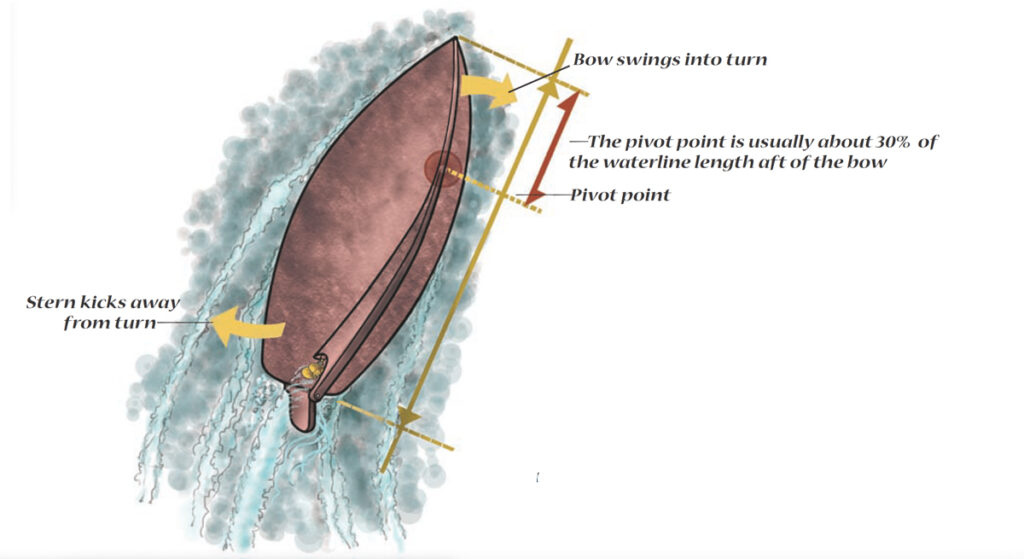

Above- All boats turn on a pivot point—a theoretical location about 30 percent aft of the bow.

How a Boat Steers

If you’re new to boats, and therefore to boat handling, keep in mind that, unlike a car, a boat steers by the stern. If you put the rudder over to starboard (to the right), the stern moves to port (to the left). Remember this when alongside a dock, for you can’t simply drive away in the same manner that you pull a car away from the curb; if you do, the stern will hit the dock.

The boat turns about an apparent pivot point—the point along the boat’s centerline about which the boat appears to rotate during a turn. The pivot point is typically about 30 percent of the boat’s length aft of the bow at idle-ahead speeds, so when your stern kicks over to port, the bow, correspondingly, and to a lesser degree, moves to starboard. The pivot point moves farther forward as speed increases, and it also moves forward in boats that are wider for their length; when a boat is backing, the pivot point moves aft. You can think of the boat’s actual path through the water as being the pivot point’s track.

How responsive a boat is to the helm depends on what kind of propulsion it has. A single engine inboard may be very responsive going ahead if it has a large rudder that turns a full 35 degrees; such a configuration may conceivably turn the boat 180 degrees in just over its own length at low speed. But backing down (reversing) in a particular direction—especially downwind takes practice, and if there’s too little rudder and too much windage, or “sail area,” forward, you can’t control the direction at all when backing.

A single outboard or sterndrive is responsive when going ahead, and its steerable propeller typically allows for good directional control when in reverse. But an outboard-powered boat with little underwater profile can be very difficult to back into a slip in a crosswind or crosscurrent, especially if there’s a lot of windage (or “sail area”), largely because the flat transom interferes with directional control. And with little underwater area, the boat’s bow will blow off quickly when the boat stops in a crosswind. In fact, I’d rather be graded on backing a single-screw, deep-hulled lobsterboat into a slip than I would doing the same maneuver in a shallow-draft outboard. That’s because the lobster-boat’s big keel serves to slow the boat from getting blown sideways, making handling more predictable.

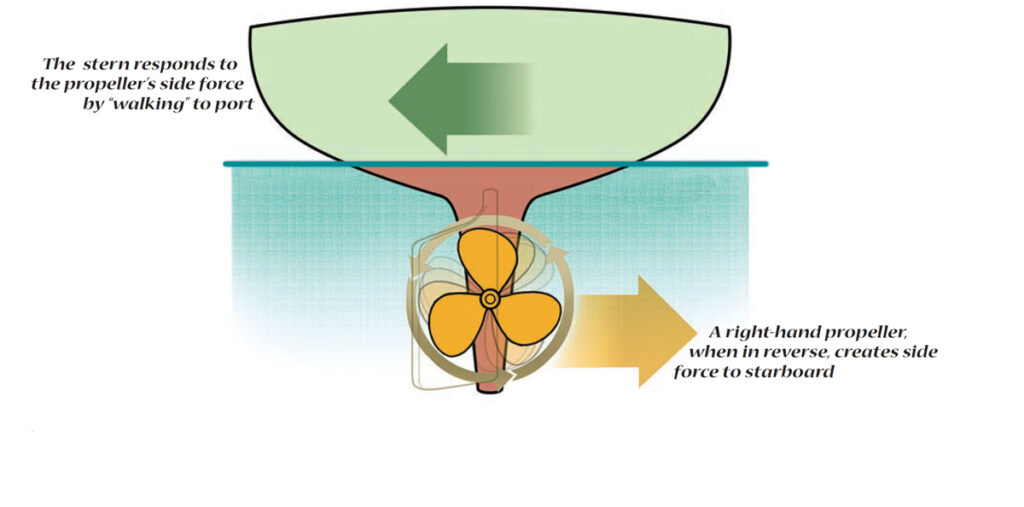

Above-A right-hand propeller turns to the left when in reverse, and for various reasons this rotation creates thrust to starboard. The stern responds to this thrust by “walking” to port—a tendency that may be put to good use in a well-planned docking.

Another phenomenon to keep in mind is that a single propeller not only develops thrust ahead and astern, but it develops side force as well. Once the boat is in gear and making headway (moving ahead), you hardly notice the side force because of the water flow against the rudder or lower unit of your stern drive or outboard, which keeps the boat moving in the direction you have it pointed. But, for a variety of reasons that we won’t go into here, when you put the single propeller in reverse, especially a propeller that’s large and slow turning, the side force is very noticeable.

Most single propellers are right-hand turning (viewed from astern) when the boat is running ahead. However, when backing down, the propeller turns to the left, and the stern “walks” to port. And because of the low speed and lack of propwash, a rudder typically has little effect on the boat’s course, at least until it gains sternway and water pressure starts to act on the rudder. The steerable propeller of an outboard-powered boat offers more control, but once the stern of either type starts backing in one direction, on many boats it can be impossible to make it change direction—to counter the stern’s sideways momentum—without using some ahead thrust in the opposite direction.

Twin engines are set up so the port engine turns to the left and the starboard engine to the right, so the side force cancels out. These so-called “twin-screw” boats are far more maneuverable than singles, all else being equal. Similarly, some sterndrives have counter-rotating propellers, one turning to the right and the other to the left, one mounted directly behind the other. MerCruiser’s Bravo 3 and Volvo’s DuoProp are the two most common counter-rotating units, and they provide much better backing control than single propellers, with no appreciable side force. They also hold a course better at low speed. For the purpose of this discussion, though, we’ll remain focused on single-propeller boats.

Now let’s have a look at how to put these forces to work for you. I often recommend that a novice boat handler begin practicing in the open water by throwing overboard something visible and buoyant, such as a life jacket (with a brick attached, to keep it from blowing around too much). Then try maneuvering around this faux dock for a while, until you get a feel for the way the boat handles. If you approach the “dock” too fast, or even drive partly over it, there’s no harm done—unless, of course, you get the life jacket or the brick’s tether wrapped around the propeller. This exercise also gives you a good feel for the boat’s pivot point, and how much time and backing power it takes to slow it to a full stop.

During this practice session, try stopping the boat with the wind blowing on the beam, and then see what happens: Does the bow blow off quickly, or does the stern? Or does the boat lie stable in this position? You’ll want to know this when maneuvering a few feet from a dock.

Docking a Powerboat

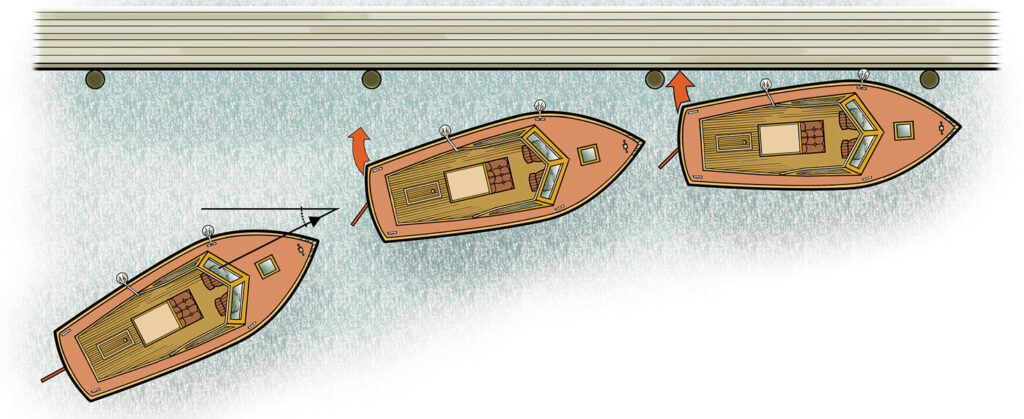

A typical docking maneuver in an inboard powered boat follows this sequence of steps:

1. Approach the dock at an angle of 15–20 degrees, making 2–4 knots; the angle and aim point will vary depending upon wind, tide, and obstructions.

2. While still moving ahead, apply right rudder to kick the stern to port.

3. Shifting into reverse causes the righthand propeller to spin left, creating side thrust to starboard; this pushes the stern to port, laying the boat parallel to the dock.

The procedure is similar in an outboard-powered boat, except that, in step 3, the helm is turned toward the dock and the engine reversed; this draws the stern in to the dock.

When coming alongside a dock in a single-engine boat with a right-hand propeller, it usually makes sense to approach port-side to; the propeller’s side force is your friend in this case. Approach at an angle of 15 or 20 degrees and aim for a spot a few feet ahead of where you want your bow to be when tied up. This angle and aim point will vary depending on wind and tide and obstructions such as boats tied up nearby. For instance, if you’re being set down on (i.e., carried toward) the dock, aim for a spot farther ahead and approach at a steeper angle.

The farther-away target will allow you to end up where you want to land in these quicker-moving conditions, and the steeper approach angle will present less boat to the wind, reducing the leeward drift. While you should move slowly when docking, you also must come in fast enough to maintain control, say 3 or 4 mph; the speed you require to maintain control is called steerageway.

Let’s assume we’re in a 25- to 45-footer. When you get about 15′ from the dock, give it a little right rudder* to start moving the stern in toward the dock, then shift into reverse, using enough throttle to come to a full stop when the boat is where you want it to be—that is, close alongside and parallel to the dock. How much, if any, rudder to give it to start the stern swinging in depends on the propulsion type.

On some inboards with big, slow-turning propellers, all you need to do is shift into reverse and the side force will pull the stern over while the aft thrust stops the boat. An outboard’s steerable propeller, on the other hand, will pull the stern in either direction, depending on which way you turn the wheel. Practice will tell you how much rudder you need in order to end up parallel to the dock in the right spot without banging the stern against it.

If you must approach starboard-side-to with a right-hand propeller that backs hard to port, then you might want to approach the dock at a steeper angle so you can kick the stern in firmly while still running ahead, anticipating and countering its momentum with the backing side force to come.

*The word “rudder,” in this case, refers to the angle of either the actual rudder or the lower unit of an outboard-driven boat.

Backing and Filling

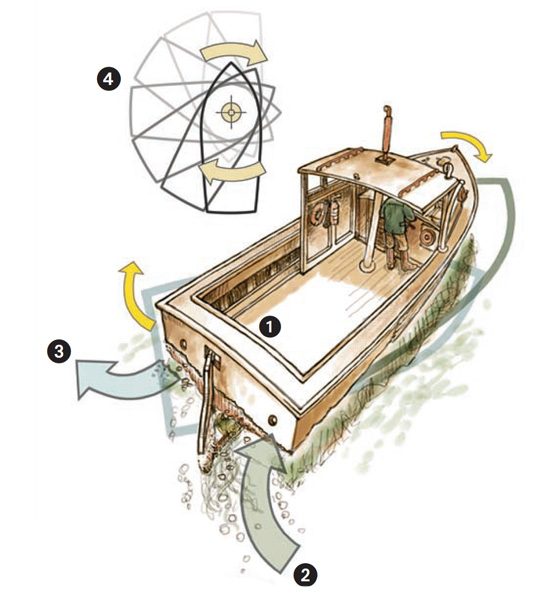

Backing and filling—a term borrowed from a tight-space maneuver in square-riggers—is the process of turning a single-propeller powerboat in its own length. It’s done by following these steps:

1. The rudder is turned hard to starboard, and remains in that position throughout the maneuver.

2. A burst of forward power kicks the stern to port.

3. Before the boat develops much headway, the transmission is shifted into reverse; the resulting side force to starboard further kicks the stern to port, while the reverse thrust arrests the developing headway.

4. Repeating with bursts of power ahead and astern will turn the boat in its own length.

This is a little like a K-turn, or three-point turn, in a car, except you leave the wheel hard over during the whole maneuver. To turn a single-engine inboard in tight quarters, say within a boat length and a half, you’ll want to turn the boat in the direction of the propeller rotation. In other words, if it’s a right-hand prop, put the rudder hard over to the right and leave it there. Then goose it ahead, wait a few seconds until you’ve just started to kick the stern over, but before you’ve picked up much headway. Then — and you can’t be bashful here — throw it into reverse (with the engine at or near idle to prevent transmission damage) and goose the engine again.

The rudder (which you leave hard over on the same side during this whole process) kicks the stern to port with the shot ahead, and the prop’s side force walks the stern to port when backing, as long as you don’t pick up sternway. Repeat with short bursts of power ahead and astern until you’re pointed in the right direction.

If you find yourself drifting too fast downwind toward the dock or another boat, drop the turning attempt, turn the boat downwind to get the stern pointed into the wind, and back out of there to safety to gain some sea room and start over. Your unique situation and your boat’s handling qualities in a breeze will dictate how, exactly, you do this.

Trimming for Better Maneuvering

Sterndrives and larger outboards have a tilt/trim control. Starting from its fully lowered position with the propeller shaft horizontal, the lower unit trims slowly about 5 degrees in either direction. This allows the boat’s trim, or amount of bow rise, to be controlled within limits. The tilt function rapidly raises the propeller clear of the water.

Bracket-mounted outboards can be more difficult to maneuver when backing down in tight quarters, since their prop-wash impacts the transom and, to a large degree, neutralizes astern thrust.

So, a good way to get around this is to first trim the motor up until it starts to tilt so more of the prop-wash shoots downward below the transom rather than against it. This will increase backing power as well as maneuverability when in reverse.

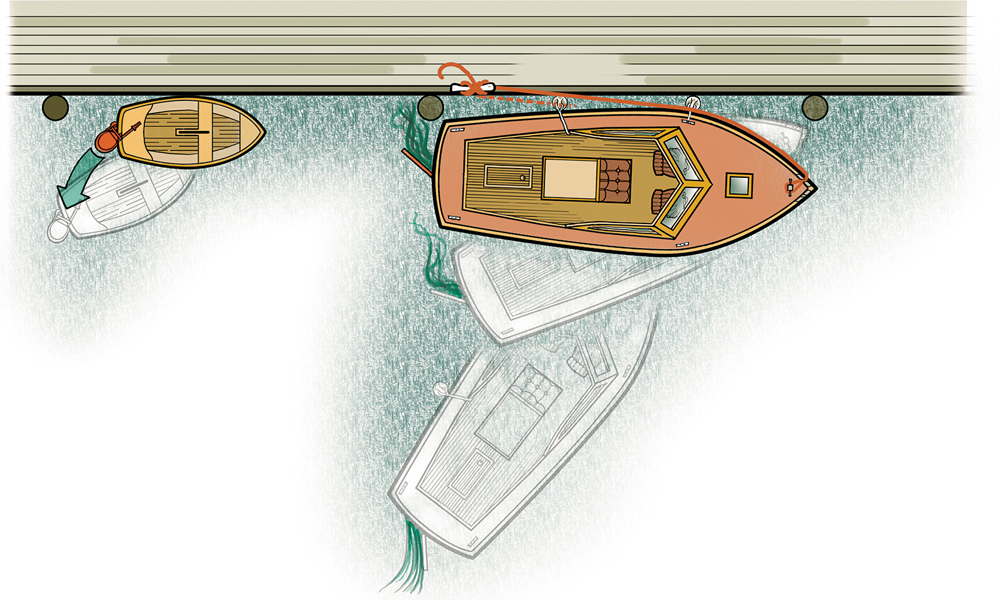

Undocking a Powerboat

Leaving the dock, or undocking, may be done in one of several ways, depending on conditions. The following steps describe how to do it when the wind is pinning the boat to the dock:

1. The engine is ahead, and the spring line stops forward motion.

2. Port rudder moves the stern to starboard.

3. When the boat is at a sufficiently steep angle to the dock, the engine is shifted into reverse, the spring line is released, and the boat backs clear.

4. If there’s no onsetting wind, an outboard-powered boat may leave the dock by simply backing away from it, drawing the stern clear.

To get away from the dock (it’s called undocking), your strategy depends mostly on whether the wind is onsetting or not, the direction and speed of the current, and how much room there is ahead and astern. It’s always a good idea to have someone on the dock give the boat a good shove off, of course, to get things rolling.

If the wind is calm and the current slack, and if you’re in an outboard-powered boat lying port side to the dock, then you’ll likely be able to back away by turning the wheel to starboard, shifting into reverse, and drawing the stern away from the dock; once in the clear, you can shift into forward and drive away.

If things are tight and there is only a little room at the dock, using a spring line is a good option, and it may be necessary if the wind is holding the boat against the dock. If you want to take the line with you, run a bight of it around a cleat or piling and tie off both ends to the bow cleat (not a ’midship cleat). Then turn the wheel hard toward the dock and shift into forward, and run ahead with just enough power to push the stern out; the spring line will prevent forward movement during the process.

When the stern is clear, back clear—or back and fill your way clear while your line handler slips the line off the dock (let go of one end and pull in the other, keeping it away from the propeller) and back away from the dock. If you’re in a single engine inboard with a right-hand propeller, and are lying port-side-to with a moderate onsetting wind, this can be hard to do as your stern will want to walk back toward the dock as you back away, but as mentioned you can get clear safely by backing and filling—with practice.

An undocking alternative (which you’ll need if your boat has a long pulpit) is to run the spring line from the stern cleat forward to the dock—and the stern cleat has to be at or very close to the transom for this to work. Here, you back down until the bow is clear, and drive right out, slipping the line as before. Depending on the configuration of your boat, you might be able to accomplish this by yourself more easily than the bow-spring method, which requires two people.

It is important to use only enough power when springing off like this, as the danger of a line parting and snapping back, or a cleat letting go, increases as more power is used. Also you have to move quickly if the wind is pushing you against the dock, so it’s smart to practice the line-handling and boat-driving choreography in benign conditions first.

If there is no boat directly behind you and you have an outboard or sterndrive, you can simply steer away from the dock and back out, perhaps with a little shove on the bow to prevent scraping the dock on the way out. Another option is to give the boat a hard shove out into open water and drive off watching your stern swing so you don’t hit the dock.

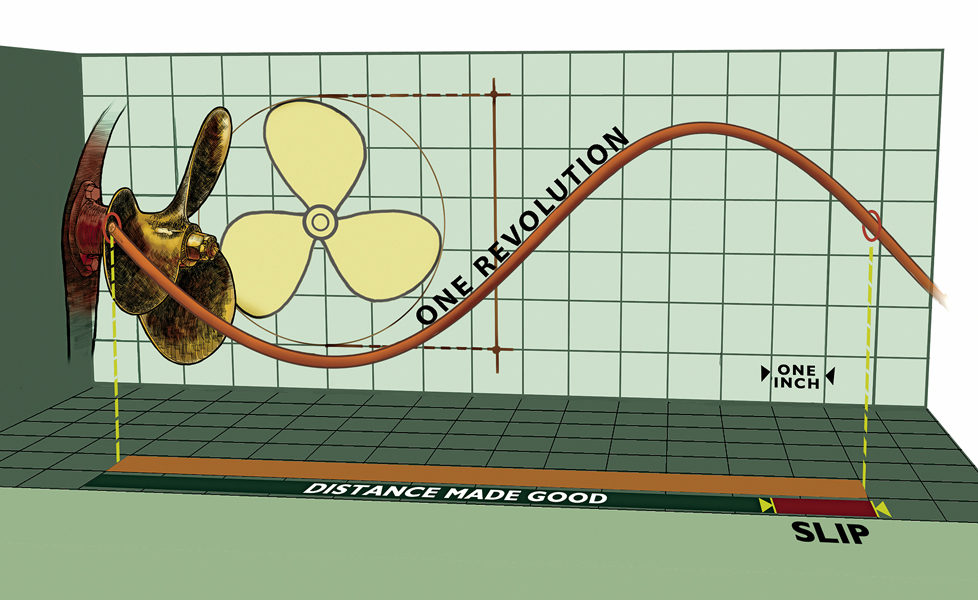

Above- A propeller’s principal dimensions are diameter and pitch. Diameter is the distance across the disc described by the spinning propeller; pitch is the theoretical distance the propeller would travel in a solid medium, in one revolution. Slip is the difference between the theoretical distance the propeller travels, and the actual distance.

Propellers

A propeller is most simply described by its two most important dimensions— diameter and pitch—as well as some other features. Imagine the disc formed by a rotating propeller; diameter is the length across this disc. (Wheel and screw are also names for the propeller.) Pitch is the distance the propeller would travel in a single rotation with no slip (like a screw turning in wood). Slip is the difference between theoretical pitch and the actual distance a propeller moves a boat forward; this difference, or slip, results from the boat’s resistance to forward movement.

Most pleasure-boat propellers have three or four blades, with the three-blade type usually being faster, while the four-blade is typically smoother-running with more blade area, and therefore more backing power.

Eric Sorensen is a powerboat consultant to a wide range of customers, including federal and state government agencies, the military, commercial-ship and patrol-boat suppliers, pleasure-boat builders, and boat owners. His book, “Sorensen’s Guide to Powerboats: How to Evaluate Design, Construction and Performance“ (McGraw-Hill), is a 500-page reference for marine professionals and boat-owners alike, and is widely recognized as a definitive source of information about powerboats.