When building a V-bottomed hull, it can be difficult to mate the edges of the two planks that meet at the chine. Aft, where the topsides and bottom meet at a sharp angle the planks can fit with a simple overlap; farther forward, however, the angle becomes increasingly obtuse, and at the stem the edge-to-edge fit is flush. The challenge is in handling the transition in these angles.

There are two common approaches for getting around this difficulty. One is to switch abruptly from a lapped seam to a mitered seam at a selected point. The other option is to employ a mitered seam for the whole length of the chine.

Where they meet, these two planks are both fastened to a fore-and-aft stringer called a chine log. The easiest way to plank a hard-chined hull is to hang the topside plank first and bevel its bottom edge as a continuation of the bevel of the chine log.

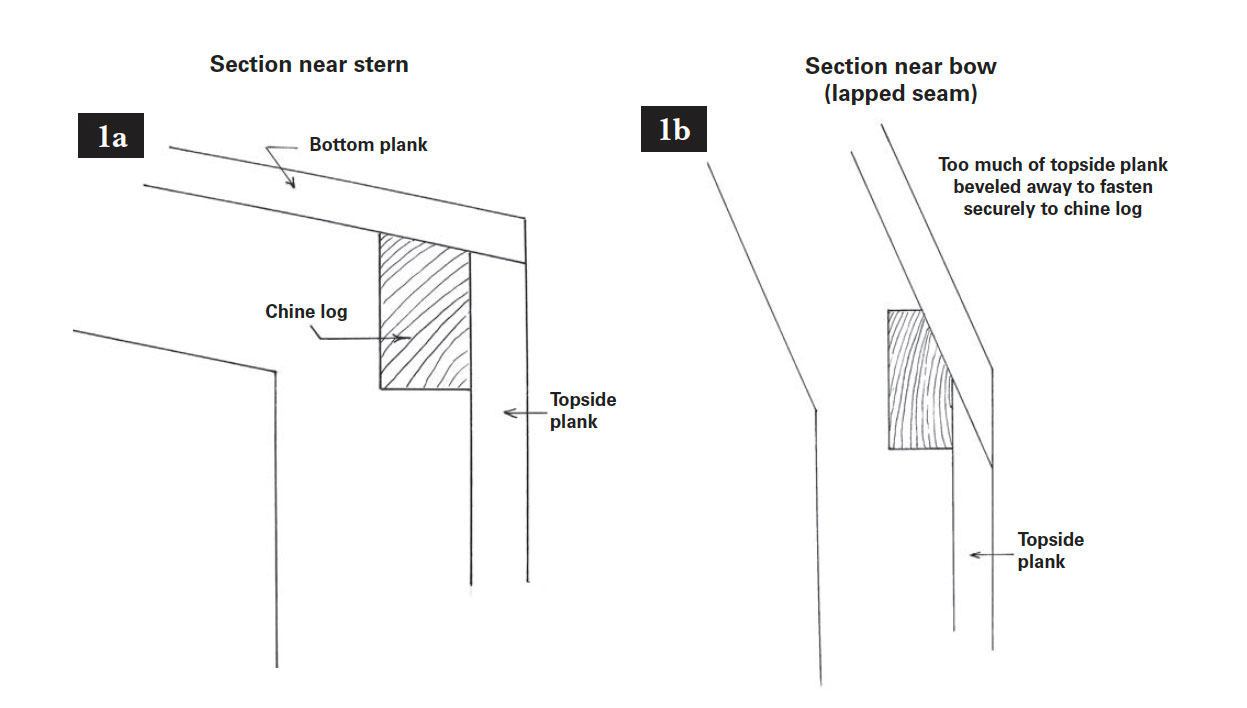

The bottom plank can then simply lap over the topside plank, as shown in drawing No. 1a. (This and all of the other drawings in this article show the hull being built upside down over a jig, as is usual.)

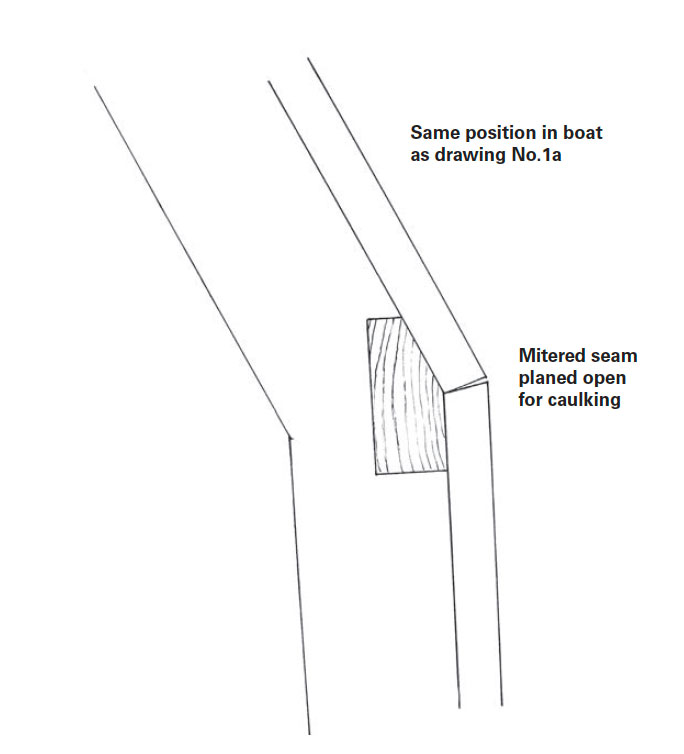

Near the stern, the planks typically form almost a right angle. Drawing No. 1a shows a cross-section through the chine of a V-bottomed hull near the transom. Drawing No. 1b shows how the angle becomes increasingly flat—and eventually nearly straight—as you work forward toward the bow. The changing angle between the topside and bottom planks from transom to bow will require that the chine and topside plank receive an increasing amount of bevel at each frame.

Between two-thirds and three-quarters of the hull’s length forward from the transom, the chine angle straightens out enough to cause a problem. Drawing No. 1b shows the amount of beveling that would be needed, hypothetically, on the topside plank at the chine in a forward section. The problem is that in this case the bevel would make it impossible to securely fasten that plank to the chine log. Here, a mitered seam is a better option.

The suggestions and drawings that follow describe two common approaches for getting around this conundrum.

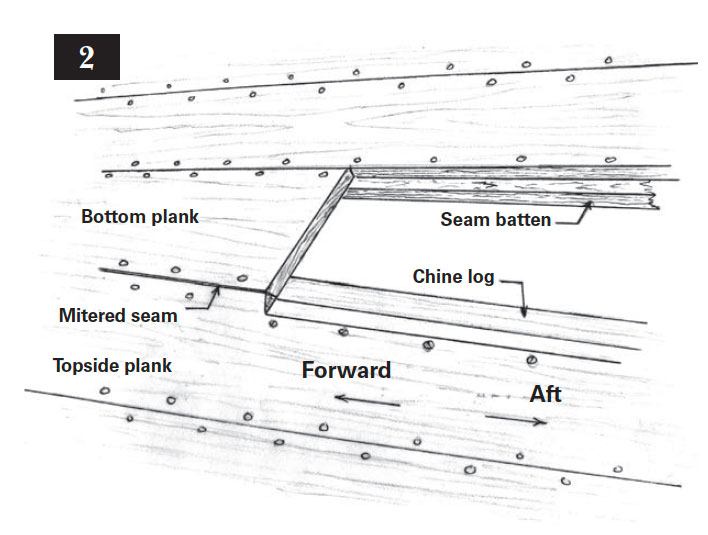

One solution would be to bevel the plank edges of both the bottom and topside planks to make a full-length miter joint at the seam. However, a simpler approach is to switch abruptly from a lapped seam to a mitered one at a selected point, as shown in drawing No. 2.

The exact transition point will be well forward, but its location will vary depending on the hull’s shape and the builder’s judgment. This can be done on a full-length plank, but for clarity drawing No. 2 shows the forward, mitered section of the bottom plank already installed.

The aft section of bottom planking, yet to be installed in this drawing, will lap over the edge of the topside plank, which is much easier to do than mitering the full length of the edges of both planks. As shown, the only task remaining is to install a butt block on the inside of the forward plank face and extending aft between the chine log and the seam batten, then the aft plank of this strake can be fastened in place.

Whether mitering the entire length of the chine seam or just its forward portion, “beveling wood” will have to be accommodated when measuring the widths of both the topside and bottom planks.

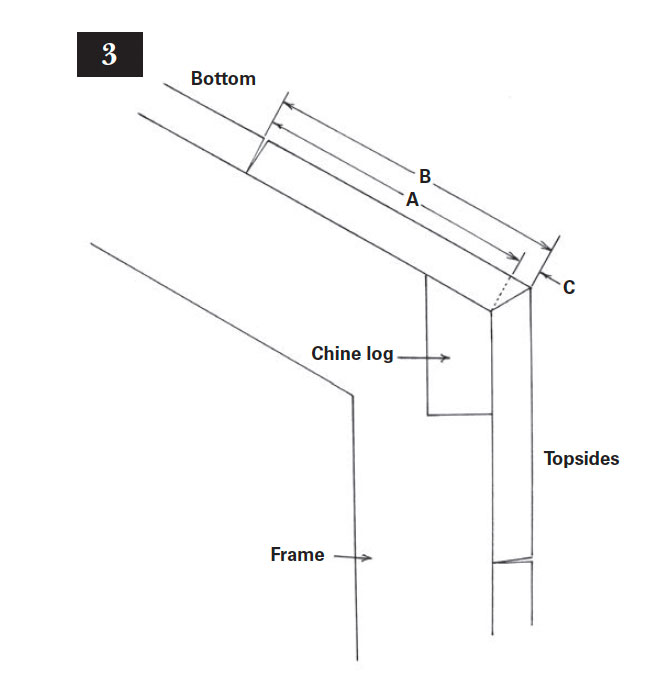

In drawing No. 3, distance A represents the width of the inside of the plank. This distance will be measured at each frame and used to draw a line on the planking stock representing the inside of the plank at the chine.

However, the use of a mitered seam means that the width of the outside of the plank (B) will be greater than the inside. This extra width (C), which is called beveling wood, is measured at each frame, and a fair line drawn through these points will represent the outside width of the plank. The plank will be sawn and planed to the outside shape, then it will be beveled back until its inside edge reaches the inside line.

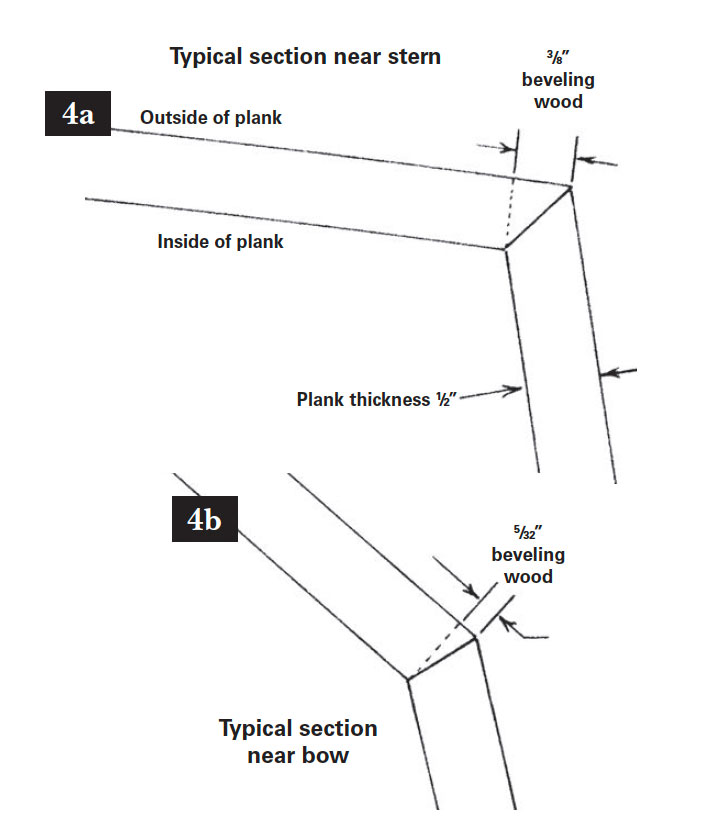

Simplified, but accurate, full-sized cross-sectional drawings corresponding to each frame will allow the amount of beveling wood to be measured accurately with a ruler or dividers. Drawing No. 4a shows a station near the transom, and drawing No. 4b shows one near the bow. In both of these drawings, the beveling wood measure is shown for the bottom plank only; however, the same amount of beveling wood will be needed on the topside plank’s edge.

This drawing shows a finished miter at the same location as shown in drawing No. 1b. Note that the mitered seam has been further adjusted to plane in a caulking bevel, which is as necessary in this seam as it is in the other adjacent seams shown in drawing No. 3.

Contributing editor Harry Bryan lives and works off the grid in Letete, New Brunswick. For more information, contact Bryan Boatbuilding, 329 Mascarene Rd., Letete, NB, E5C 2P6, Canada; 506–755–2486.