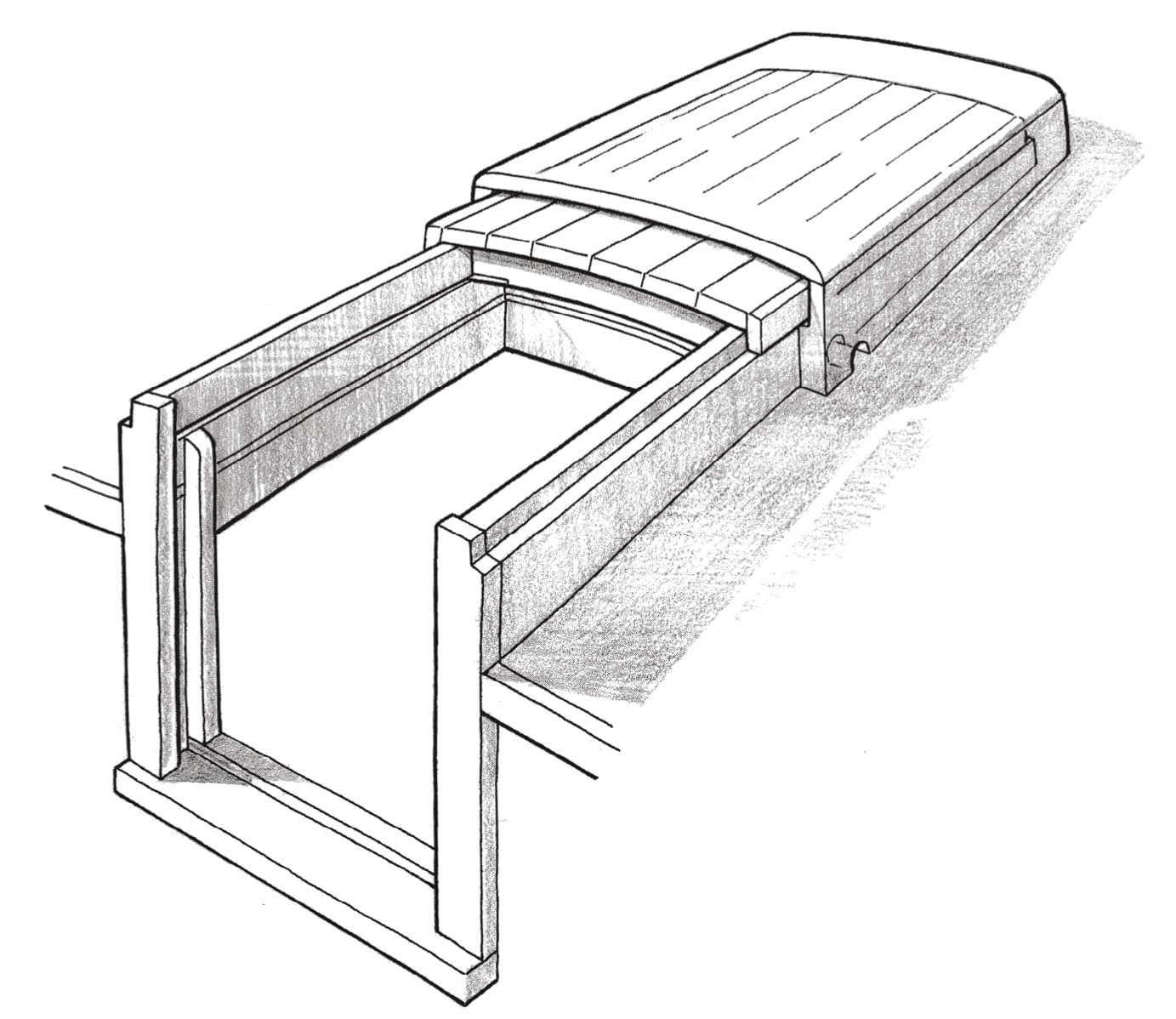

So you have the deck on, with two openings in it. The big one is to be covered with a structure (labeled, variously, trunk cabin, coach roof, deckhouse) that will provide headroom, admit air and light, keep out water, wind, and mosquitoes, and not detract unduly from the grace and elegance of the vessel.

Mr. Rudyard Kipling once remarked that there are nine-and-60 ways of writing tribal lays, and every single one of them is right. So it is with this structure. I’ve tried most of them in the last 50 years, and have finally settled upon a routine that works well for me. It even produces a result that fulfills most of the above listed requirements. It demands no special aesthetic sense, inherited instinct, or awesome skill of hand and eye. The end product looks amazingly like the picture which shows a profile having a skyline at the top, a line where top meets side, and a third where side meets deck. It also shows an end view of the whole business, showing the amount of tumblehome ( or lack of it) in the sides and ends, and the crown of the beams in the house top. But unless the designer is very good, indeed (and unless your work, to this point, in the matter of sheer, width of side decks, and consistency of main deck crown, is absolutely flawless), you will be faced with the need to make small adjustments-which take time and shake your confidence if done in a hit-or-miss manner, but which proceed smoothly and inevitably with the right technique and equipment.

The beam-crown pattern

The first thing you’ll need to build the house is a beam-crown pattern, which in this case should be a light board slightly longer than the greatest width of the house, with a convex crown cut into one edge and matching concavity cut into the other (Figure 15-1). We’ll assume for the moment, in charity, that your designer has been content to use a constant crown for the full length of the house. (I’ve known some designs that required every beam to be different from the one behind it; but I trust that the perpetrators of these horrors have now all been eliminated.) This crown is, very likely, described as an arc with a radius of 7 feet 3 inches (or whatever) and is, of course, easily marked by tacking one end of a slat to the floor, measuring from the nail the length of the given radius, and marking the path of that point along the length of your pattern. For a known radius (and if it is short enough to fit an uncluttered space on your shop floor), this is the sensible way to describe it.

Figure 15-1

Figure 15-2

But suppose the S.O.B. (this should, of course, read N.A.) describes the crown as having a height of 83/4 inches in 7 feet 1 ½ inches length. You can lay off this line on the floor and swing arcs of experimental radii until your knees and patience have both given out and you’ve achieved a curve that comes very close to hitting all those points. Or you can attack the problem as in the accompanying drawing (Figure 15-2, steps a,b, and c), which is self explanatory and uses up what little I remember from my high school geometry lessons.

Then there’s the textbook method, known to all students of naval architecture, whereby you draw a doughnut (which sits on a line like the sun on the horizon) and carve it into strange sections whose heights are spaced at ordained intervals along the lines. Spring a batten to these marks, and there you have it-the almost perfect arc, flawed minutely, if at all, by the irresponsibilities of a less-than-perfect homogeneous batten. My head aches when I think of it.

Then there’s the right way, which deserves a paragraph in itself.

You draw a line, the length of the beam. At each end of the line, stand a rubbing point in the form of an eightpenny nail (or any other size you have handy-I don’t want to be too damned didactic), and halfway between these nails, measure up, from the line, the height of the crown you want in the beam. Find two straight-edged boards, each slightly longer than the longest arc you expect to need (4 inches sliced off the edge of an 8-foot sheet of plywood come straight and handy). Snip off a corner on each so that you can butt the points together at the mid-crown mark while the edges are pushed against the nails (see Figure 15-3). Tack some laths across to keep the two straightedges touching at the point and at a constant angle to each other. Now, if you slide the point from the center mark to one nail and then to the other, keeping the straightedges against the respective nails while sliding, the path of the point will be a perfect, flawless arc reaching from nail to nail, and the arc will be exactly the right height in the middle. Run a pencil point, of course, at the end of the tip, to mark the pattern you want to cut. This truth machine can be readjusted in moments to fit any beam whose length and height of crown are within its scope. (Soon we’ll be equipped to determine the length and crown of any beam in a tortured housetop, and we’ll be happy we have this quick-and-dirty way to mark it out.)

Figure 15-3

Now, in sweet charity, let’s assume that the design calls for constant crown, and that, about six days from now, you will need 16 beams, identical ( except for length) in every respect.

If you have on hand some clear, sweeping planks that grew in a curve to match your pattern, then you may rest serene and go on to the next step, knowing that you can saw them out when they’re needed. But beware-such sweeps have been known to change shape after sawing. Don’t plan to saw your beams out of straight grained stock, because they’ll be likely to check open and break where the grain runs across the curve. You could steam-bend the stock over a form built to a tighter curve, precisely calculated to produce the arc you want when the beams straighten out-ever so slightly, indeed, but inevitably, and not all to the same amount. In view of these difficulties, you’d perhaps best plan to make them of glued laminations, thus:

Build a gluing form (or two, or three, if you have the strength) by sawing out a 2- by 2-inch rainbow and mounting it on a backboard like a prize fish (see Figure 15-4). The radius of the top edge of the two-by-two should theoretically be shorter (by the depth of the beam) than the radius of the finished beam.

Figure 15-4

Saw out and smooth the stock for the laminations. The strips are too rough as they come from the saw and should be planed before gluing. You must use a minimum of five layers to produce a beam that will hold its exact shape when the clamps are off. When we planked with mahogany (which was the least expensive wood, all things considered, that we could get), we sawed up the edgings for beams. We thereby impressed the owners with our dedication to fine craftsmanship, and doomed ourselves to sanding and varnishing the beams. Lacking mahogany, we used fir or spruce, with an occasional layer of oak or ash on the bottom.

Each morning, first thing, mix a coffee can of Weldwood glue (consistency of thick cream), line the gluing form with old newspapers, smear the strips, set one C-clamp to tie down the middle of the bundle, and clamp both ways toward the ends, placing the clamps no more than 6 inches apart. If you have two more forms to fill, you’ll need a minimum of 30 clamps to squeeze three dinky little 5-foot beams. Take the clamps off next morning, ship on the lobsters, and set ‘er again … and five days later you’ll have enough beams to frame the length of your 15-foot house. And high time, too, because you’ll be ready for them.

Without further arguments, preparations, or apologies, let’s build this house.

Fitting the house ends and cornerposts

First, cut out and fit the two ends. (I assume that you have boards wide enough, or that you have glued two pieces together to get the necessary width.) The construction drawing should give you the height at the corners; your deckbeam pattern should give you a fairly accurate line for the bottom edge of each end; and the housetop beam pattern should give you the top edge of each end ( allowing for the thickness of the decking to lap over the beams and yet enough extra to allow for trimming and beveling). The ends will, of course, be cut with the correct amount of tumblehome, as shown in the construction section through the middle of the house. If the designer leaves such a detail to your judgment, which seems unlikely, and if you want my advice, slope them in l inch to the foot of height, or thereabouts. (Forty years ago we always set them plumb, and they looked horrible.) Make the ends square, and about 1/4 inch short of the corners of the opening in the deck. Leave the bottom edges (which sit on the deck) square to start with. The after end will likely be plumb in profile view, and should need very little beveling after you have scribed and dressed it to a light-tight fit to make it stand. Unless the designer goes for a rakish look, the forward end of the house will very likely stand at about 90 degrees to the centerline of the forward deck-and therefore will need only scribing and trimming to get that perfect fit against the deck.

Cut the opening for the companionway in the after end, and set up both ends in position with two bar clamps on each, as shown in Figure 15-5. (Their inner faces will, of course, be exactly flush with the trimmed-off deck opening.) Mark for the bolts that will tie the ends to the deck frame at least four in each. The outer bolts should be not more than 6 inches from the corners; put two through the sill in the after end, and perhaps two more 3 inches clear of the companionway opening. All these bolts should be plumb in the athwartships plane, and you might take a quick look to make sure none of them lands on a deck fastening. Now unclamp the ends, square across from the lines on the top and bottom edges, mark the exact center with a prick-punch, and get ready to drill for those bolts.

Figure 15-5

This drilling process may appear to be extremely difficult, if not hazardous, with the chance-nay, likelihood-of ruining a very expensive piece of wood. I once thought so, and felt smugly thankful that I was endowed with the skill to drill these all day long and never miss one-until I lent the gear and described the technique to a thickheaded, brash amateur, and sat back in ghoulish glee to await his report on wayward drills-only to have my pride fall in the shavings when he came back the next day, frankly puzzled that I should have had any doubts. What’s supposed to be difficult about that? He did it just the way I told him. Since then I’ve advised a dozen more young boatbuilders, and only one needed to be threatened with the ancient and traditional aid of a pig turd hung on a string from the end of his nose, so he’d know for sure which way was straight down.

Take a scrap of 1- by 12-inch board, mark a half dozen straight lines on one side of it, clamp it on edge on the floor, and practice the business of edge-drilling. You need a 3/s-inch drill, 18 inches long. You can get one, labeled “bellhanger’s drill,” from an electrician’s supply store, or you can weld a 5/16-inch shank to a “jobber’s length” machinist’s drill. (You will, of course, call this a bit, because you’ll use it in a ½-inch electric drill, and you don’t want to confuse the terms.) Start the bit exactly on center, where marked with a prick-punch; line it up by eye with the line on the side of the board, and proceed to bore down a little more than half the width of the board. Turn it over, aim as before, and bore down until your bit enters exactly into the hole you bored from the other edge, or almost exactly.

Figure 15-6

You’d best make a reamer by flattening with a hammer one end of a piece of 3/s-inch rod and then filing it (see Figure 15-6). Spin this up and down the hole, and you’ll know for sure that the bolts will go through without binding. Practice with three or four holes, and you’ll gain the necessary confidence and faith to tackle those that count. (Note, in passing, that this skill will be needed when you build an edge-bolted rudder, centerboard, mast step, or footwell.)

Figure 15-7

And here they are, those that count, to be drilled as follows: Clamp each house end to something so that it stands top edge up, lower edge on the shop floor (see Figure 15-7). Counterbore 1 inch deep with a ¼-inch bit for the bolt heads (which will be 3/s-inch hex nuts) and stand astraddle of the victim with drill in hand and mind serene. Sight down the pencil line and both sides of the board (it helps if you can wall your eyes at will) and press the trigger. Don’t bear down hard. Think of a hummingbird hovering over a blossom. Haul out the bit ever and anon to clear the clogged shavings. As in your practice sessions, bore halfway and a little more; tip the board over, clamp, and bore ’til the bit breaks joyfully into the tunnel you started from the other side of the mountain. Comfort yourself with the thought that there remain but 23 of these to be done ere the house is finished, and proceed, with no further help from me, until you have these ends all bored and reamed.

Clamp the house ends back in place, and run the long bit down each hole in turn through the deck and deckbeam. Measure for all the bolts-from the top of the nut at the top end to the underside of the beam, plus 1/4 inch. Counterbore in the beam 5/s inch up, to take a standard 5/16-inch washer, which will spin up the thread on your 3/s-inch bolt. Make up the bolts, start them in their respective holes, unclamp again, ream holes through the deck and beam, lay a good bead of sticky stuff (butyl rubber, for instance) and maybe a half-strand of caulking cotton, looped cautiously around the bolt holes-and pick her up tenderly, lift her with care, and tap the bolts home. Put on the washers and nuts, but don’t try to squeeze the hell out of the assembly just yet. You want the goo to harden a bit and adjust itself, so some of it will stay in the joint when you tighten up all around. Saw out and clamp a piece of scrap across the companionway opening to reproduce the crown you cut out of it. If you’re satisfied with the way these ends stand in profile (and you’d better be, because you aren’t going to change them much), brace each with a slat from the deck, and prepare to put in the cornerposts.

I differ from most yacht designers. They draw a perfectly fitted, one-piece rabbeted cornerpost. I make it in two pieces, for the following reasons: (I) It’s much easier that way; (2) where the hell am I going to find a piece of mahogany that thick? (3) if a leak develops, I can always remove, resmear, and replace the outer piece, just as I would a beat-up outer stem on a dory; and (4) it’s easier my way.

Figure 15-8

With that point settled, saw out a piece of mahogany, locust, black walnut, or whatever, about 2 by 5 inches and long enough to make the two forward corners, with a little extra to spare. Set your bevel square to the angle between the end of the house and the side-to-be. Mark this angle on the end of your two-by-five (see Figure 15-8), and cut each of those corners with a handsaw or a tilting-arbor table saw (or even by hand, if all else fails). Now cut the piece in two, and fit each half to its corner-tapering from the deckline down on the outside and forward faces-until it is snug to the deck frame and fits tightly against and follows the tumblehome of the house end. Finish shaping the post to your heart’s desire. I always run a groove down the inner face, and cut the edges square, so the face pieces and beam ledges can butt against them, as shown in Figure 15-8. Glue and screw-fasten the post to the house end, but do not fasten the lower end to the deck frame.

The cornerpost at the after end will be treated in just the same fashion, but will come out of a narrower piece of stock.

The house sides

You now have, with these cornerposts, a bearing surface for anchoring your clamps when you are springing the house sides around the temporary framework. This last, which you are about to install, is the key to the entire business of shaping, fitting, clamping, and fastening the house sides. Here is how you make the framework:

Saw out about a quarter of a mile of 1- by 4-inch straightedge stock. Climb aboard, pick likely spots that are roughly one-fourth, one-half, and three-fourths of the distance along the length of the house. Tack a piece of your one-by-four to the under edges of the fore-and-aft carlins ( and exactly square across the centerline of the vessel) at each of these spots. Clamp a vertical piece, its bottom resting on the inside of the hull planking, sloped inward to match, roughly, the tumblehome showing in the already installed after end of the house. Scribe and cut the bottom end so it can be tacked to the planking; fit it in the way of the carlin to bring its outer edge to the deck edge; set it exactly at the right amount of tumblehome; and nail it to the crosspiece and the carlin. Fit and fasten the identical twin on the other side, cross-brace the two as shown in Figure 15-10, and go on to install the other three sets.

Figure 15-9

Figure 15-10

You will notice that the actual tumblehome on the forward end of the house is greater than at the after end-this effect is the result of the slight rake aft in the profile view. So split the difference when you set up the framework at the three-quarter distance-that is, give the framework a bit more tumblehome than the middle one shows and a bit less than is apparent when you sight past it to the forward cornerposts. Don’t worry too much about this, but try to make the two sides alike.

Now you need only a centerline (profile) along the middle of the house, and you’ll be ready to mark the exact shape of the house sides. This centerline may, in your construction profile, show as an old-fashioned swayback dip, the look-of-tomorrow hump, or a straight line parallel to the waterline. The last, I think, usually looks right and is certainly the easiest to work with, especially if you plan to deck with plywood. (The dipped or humped profiles inevitably generate compound curves, which plywood abhors.)

Stand, therefore, on edge, from the midcrown of the aft end to the mid-crown of the forward, a 1-by 6-inch straightedge, clamped solidly in place. (You can obtain the same reference line with a tight string, but you’ll be forever pushing it out of true and waiting for it to stop humming.)

The next operation is the payoff for all the effort described above. Take your beam-crown pattern, lay it against one of your temporary uprights, with its top edge against the bottom of the fore-and-aft straightedge. Adjust the pattern ends up or down (above the deck edge, on the outside of the vertical uprights) until the heights are exactly the same both port and starboard. Mark a fine, bold line on the athwartships face and the outboard edge of each upright (see Figure 15-11)-and go on to do likewise on the other two sets. As surely as night must follow day, these points (five in all, counting the ends) must delineate the inner top edge of the house side, at the under surface of the housetop.

Figure 15-11

Figure 15-12

You must now mark for the lower edge of the house side, which is to fit the deck with a watertight joint. This line is most easily obtained by scribing the line on a spiling board and then transferring it to the board that will form the house sides, as shown in Figures 15-11 and 15-12. (I assume that you know how to take and transfer a spiling; my only warning in this case is that you take special pains to assure that your spiling board is comfortable and relaxed before you mark it.) Now, while the spiling board is in place, mark each of your five height reference points, and lay off the respective heights above the line of the lower edge. Run a batten through the points for a fair line. These heights are for the inside of the house side, and must be increased at the top by the amount you’ll lose when you bevel the bottom edge to fit the crown of the deck.

Proceed now to saw it out and bevel the bottom edge of the side to fit the slope of the deck. Clamp the side in place, around your uprights and to the cornerposts. If your spiling was accurate, the side should lie comfortably, with its lower edge touching the deck all the way. Snug it down with three bar clamps, note that the top edge is high enough, mark for trimming the lower edge for fit, mark for the end cuts at the cornerposts, and climb aboard.

Figure 15-13

Now is the time to mark for the edge bolts. (See Figure 15-13.) As in the house ends, there should be one bolt not more than 6 inches from the corner. For the rest, you need only to bear in mind that they should be roughly at right angles to the carlin, and they must not land where a deckbeam ends, nor where a tie-rod comes through the carlin, nor less than 2 inches from a portlight hole, nor more than 20 inches apart, nor in the way of fastenings in the deck, nor on a strength-bulkhead at the mast partners. You may make two false starts and squander several minutes before you arrive at the perfect pattern.

Anyway, unclamp, correct the fit on the bottom edge, cut the ends where marked from the cornerposts, and mark out an identical twin, complete with the bolt locations and a little extra length on one end (you’d be surprised to know how many boats are a bit longer on one side than the other; and it’s always the shorter side you measure first). Now set ‘er up on edge, and counter bore the holes through the carlin; smear with Wonder Cement; drive the bolts and screw-fasten to the cornerposts. Pluck out all that temporary framework, and prepare to install the beams.

Fastening to the beam ledge

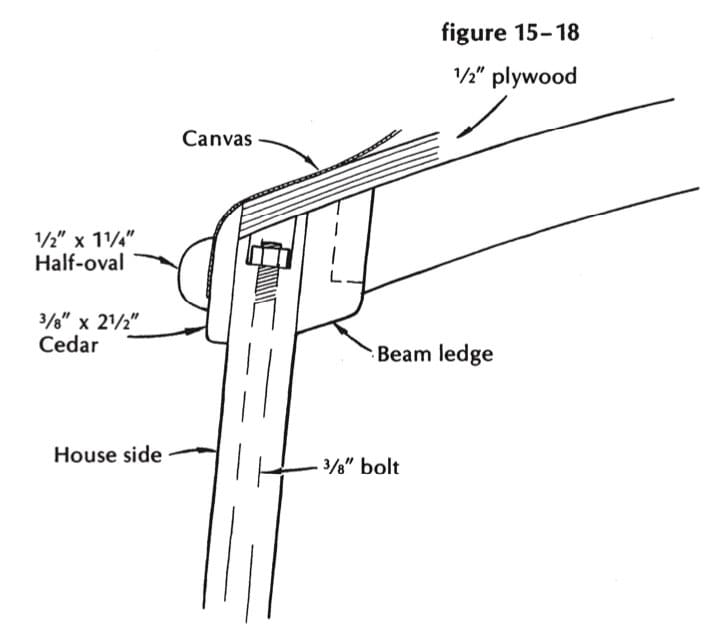

As usual with any job you start in a boat, there are a half dozen things to be done before you begin the serious business. Right now you have to fair off the tops of the house sides ( to the exact heights obtained from that temporary framework) and install a beam ledge. Use the concave edge of your beam pattern, or one of the beams themselves, laid across, to give you the angle … and be very glad, indeed, that you countersunk the bolt heads deep enough. The beam ledge, probably made from the same stock as the house sides, and ½ inch deeper than the beams, can be sawn to the correct bevel ( the same on both the top and bottom edge) and sprung into place inside the top of the house sipe. When you fasten the ledge (with glue in the joint, and screws from the ledge into the house side), try to keep the screws clear of the spots where the beam ends will land. This beam ledge, or a reasonable facsimile of it, sawed to shape, will of course be carried across the tops of the house ends.

By the time you have fitted all the above, and the beams, and the companionway frame, and the mast partners, and the face pieces, you may think back with sadly won wisdom to the day when you were fitting planks, and foolishly thought that the hull was the big problem.

Figure 15-14

So what type of joint do we make where beam meets ledge? Your designer very likely shows exquisitely fitted dovetails (Figure 15-14), the mark of the master craftsman who Really Cares. (We are probably safe in assuming that the man who calls for full dovetails is at least twice as conscientious as the slipshod fellow who is content with the half version. In my youth, I encountered three designers, whose awesome talents enabled them, respectively, to draw a full-sized toilet in a sailboat not much bigger than said fixture, to draw quarter-beam buttocks straight as a string, and even to specify Philippine mahogany for planking-on a lobster boat, mind you. Needless to say, each of these giants of the trade could have drawn full dovetails with absolute precision wherever wood met wood.) I say, to hell with dovetails, except in the corners of a sea chest, or any other place where they’re fully exposed and will draw oohs and aahs. I think they are holdovers, in a very conservative trade, from the days when fine timber and skilled labor were cheap and plentiful, and metal fastenings were very expensive indeed. I hasten to add that I am not, in the above diatribe, talking to earnest young idealists, worshipers at the shrine of ——- (you can fill in his name), but mostly to lazy old b——s (you can fill that in, too) like me, who are even yet, in our dotage, trying to figure out a way to get the job done on time, before the money runs out. To that end, one of the first sweet babies to be tossed to the wolves is the dovetail.

Having run myself aground in the great stream of historical continuity, I drag myself out on the bank and refer you to two diagrams, shown in Figure 15-15. The way I usually join beam to ledge is depicted in Figure 15-15a: Cut a plumb-sided alcove into the beam ledge, about ½ inch deep, the full width of the beam-so that you get the little chin whisker bearing against the house side and looking as if it grew there. (I assure you, it was a great day in the McIntosh Boat Shop when I not only graduated from ½-inch to ½-inch putty, but also learned to mix glue and sander dust for Invisible Mending. It has come in handy for those housetop beams.) Figure 15-15b shows a system easier yet: cut a sloping notch, starting at half the thickness of the beam ledge at the top, and running out to nothing at the bottom of the beam. This takes some precise cutting on the beam ends ( or some very delicate work with the putty knife and Mending Compound), but it’s a perfectly satisfactory joint, if you put enough good bronze fastenings in it, and it’s much better than a dovetail.

Figure 15-15

By the time you have fastened a plywood lid over the entire business, it will be strong enough to jump on from 10 feet up-and you can be sure that some joyful 200-pounder will do it some day. (Or some night, if it’s the dark of the moon, and he doesn’t realize that the Eastport tide has dropped 8 feet since he went ashore. I hope he breaks a leg.)

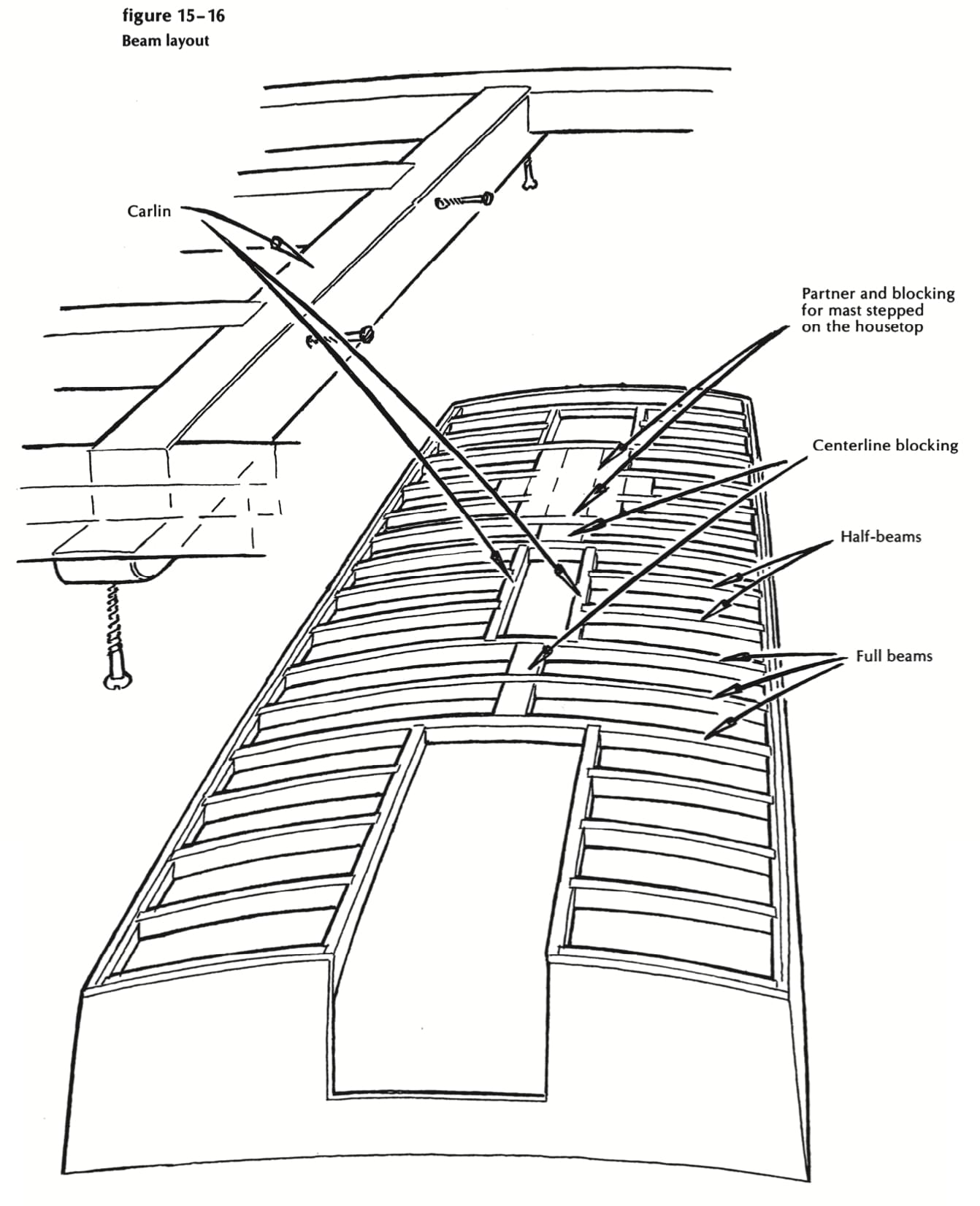

Back to the construction plan to get the beam layout. This will be complicated only by the length of the companionway opening, the location of the mast partners (if the mast steps through or on the housetop), and, usually, a skylight aft of the mainmast and an escape hatch forward of it. Each of these openings will require the fitting of half-beams to fore-and-aft carlins, stringers, or whatever you want to call them. Locate, fit, and fasten the beams at the ends of these openings; stretch a tight string from the stem to the transom, and mark the exact centers of these main beams. Fit and fasten the fore-and-aft members (including the mast-partner blocking, if any), and install the short beams two on each side, usually, in the way of the companionway, one on each side at the partners, skylight, and forward hatch. I always make the fore-and-aft members somewhat deeper than the beams, with a simple butt joint against the beam, and the extra depth extending under it, for the owner to bang his head on (see Figures 15-15a, 15-16).

Figure 15-16

The blocking between the mast-partner beams is, of course, no deeper than the beams and when I install it, is likewise a simple butt joint against the beam, pinned in place with plenty of spikes, and tied together athwartships with edge bolts before and abaft the mast hole. No rebates, lodging knees, or keylocks. Fit the short beams to the fore-and-aft members with the same end joints as described above: into the alcove in the house side, and with the simple sloping notch at the inboard end (Figures 15-15a, 15-17). If the design calls for hanging knees at the companionway and partner beams, fit these now, before the rest of the long beams are installed and cramp your work space.

You will forgive me, I hope, if by making the following recommendations I seem to doubt your ability to mark and cut so simple a thing as a deckbeam. I only fear that in your youthful exuberance you’ll try some shortcuts (in a figurative sense, that is) and wind up with some beams that don’t quite reach… I, too, have oft been told of the Inscrutable Oriental Craftsman who needs only look intently at the gap to be filled, and goes to the lumber shed and cuts a piece that falls exactly into place. It’s an instinct, they say, totally lacking in us Westerners, who can’t do half as well with all our steel tapes and bevel squares. (And astrolabes and prolapses, as one critic said.) All right, I admit it; but I don’t think you are any better at this business than I am. So, study Figure 15-17, then cut.

Figure 15-17

Be bold, cut to the mark. Start with a long beam, and move forward to a shorter length if you mess it up. Tack them all in place with a fivepenny box nail at each end; anchor a slat to the forward end, 5 inches clear of the centerline; and space (and tack to the slats) the centers of the beams exactly as they are spaced at their ends. Mark and cut 1- by 4-inch blocking to fit between the beams right down the centerline of the housetop. Fasten them as shown in the diagram.

Fit, round off, and fasten the outer pieces of the cornerposts, with plenty of sticky stuff in the joints. Fair off everything smooth as a smelt. Lay the deck (housetop, that is), consisting of doubled plywood with joints staggered and glued between, or matched pine or cedar in narrow strakes, or single-thickness plywood butted on centerline blocking, or whatever else you fancy. You can even put white Formica on the underside, if you want. Fasten well, especially around the edges. Trim off, and glue and-screw a 3/s- by 2½-inch piece of trim molding all around. (See Figure 15-18.)

Figure 15-18

Fill all the punched-down fastenings with polyester putty, the boatbuilder’s friend. Cover the top with canvas, loaded with paint, if you’re old-fashioned like me; but I’ll forgive you if you use that smelly stuff-though not on matched pine, unless it’s plenty thick and independently strong. Bring this cover down around the edges, and seal the edge of the canvas with half-oval molding, hollowed out to hold sticky sealant. Remember that any exposed canvas underedge will act as a wick to draw sweet water into the joint, and the rot spores will devour your fine work before you realize what’s going on.

When you fit bronze portlights with a sleeve ( called a “spigot” in the trade) that lines the opening in the wood, be sure to leave plenty of clearance at the top and bottom, because the house sides will inevitably shrink, and you will have to tighten the hold-down bolts. But you can’t squeeze these ports, and the house sides will inevitably split to relieve the strain.

You aren’t entirely out of the woods yet (perhaps we should switch the figure of speech, and say you still may need some guidance across the bar)-so read on for more details.