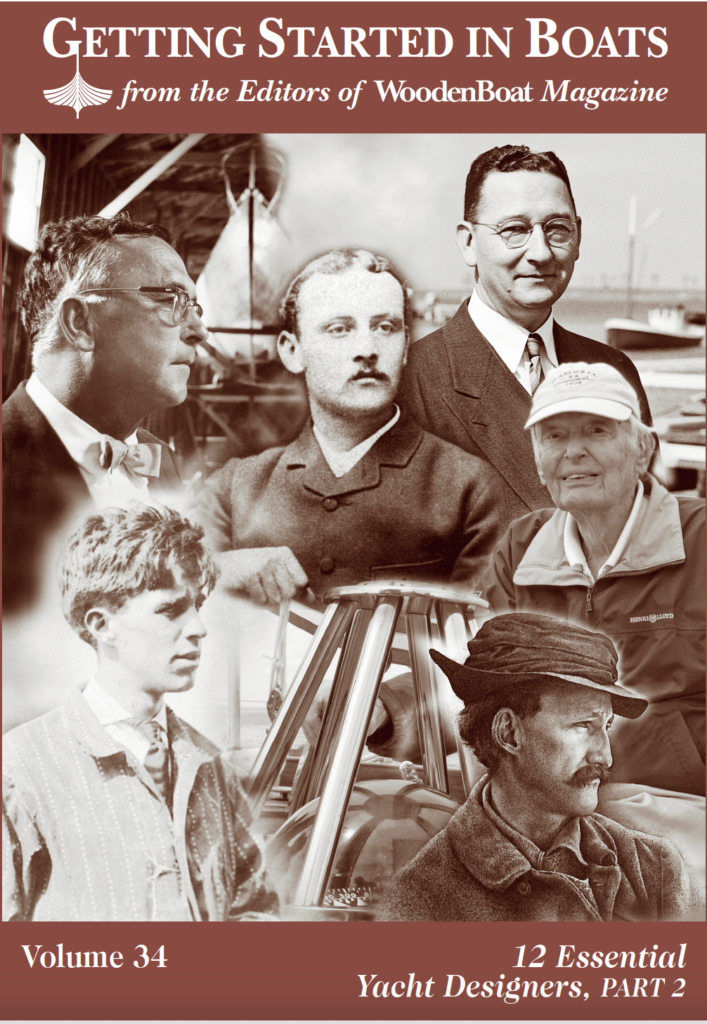

BURGESS • FIFE • GEARY • HUNT • RHODES • STEPHENS

Some designers achieve greatness mostly through the beauty of their designs—they are apt to rely on traditional proportions and only small, incremental innovations to ensure good performance and avoid mistakes. This is how the majority of working craft and yacht types evolved, in a process akin to evolution in the natural world. While at first glance this approach might seem primitive, it is the safest and most conservative method and over the years has produced many of the yachts we admire most.

Others are innovators, whose work is often criticized when it first comes out but later is seen to have advanced the field to the benefit of all. As time passes, that which is good technically tends to become good aesthetically, either through an adjustment in people’s tastes or through discovery of a new aesthetic that may have been hidden, at first, in emerging technology. Plywood, for instance, was not felt to be an aesthetically pleasing material until recent years, when a host of designers seem to have unlocked its visual potential. The ultimate example may be rotomolded plastic construction, in which almost any shape is as easy to create as any other, resulting in whitewater kayaks, for instance, whose shapes are starting to resemble living things as much as boats, and have an appeal all their own.

Innovative designers are more apt to be numbered among the greats, because they are more likely to achieve sudden breakthroughs in speed, or comfort, or practicality, as the case may be. Often an innovator will perceive in new technology the possibility of lighter structures for a given strength, an advantage that would often be used to increase the percentage of a boat’s overall weight that is in the ballast, giving her the ability to carry more sail and thus be more powerful. Some major advances have occurred by putting together long-existing characteristics in new combinations. Today, innovative designers are grappling with the implications of computer-controlled cutting machines, which seem poised to start a whole new round of innovation.

In this issue, our subjects are Olin Stephens, Philip Leonard Rhodes, Charles Raymond Hunt, W. Starling Burgess, William Fife III, and Leslie Edward “Ted” Geary. In Part 1 of our 12 Essential Yacht Designers feature, the subjects were John G. Alden, William Atkin, Bowdoin Bradlee Crowninshield, William Garden, William Hand, and Nathanael Greene Herreshoff.

As mentioned in Part 1, further reading about all of these designers and their work can be found in numerous WoodenBoat magazine articles or in biographies written about the designers or in books written by the designers themselves. The books listed at the end of each segment in Part 2, as in Part 1, are available through The WoodenBoat Store.

William Starling Burgess

1884–1962, Boston, Massachusetts, and New York, New York

W. Starling Burgess designed boats ranging from small daysailers to the largest racing yachts, such as the J-class RAINBOW, right, which was launched in 1934 at the Herreshoff Mfg. Co. and successfully defended the AMERICA’s Cup that year.

W. Starling Burgess, son of the famous yacht designer Edward Burgess, was probably less influenced by his father, who died when Starling was very young, than by his father’s friend N.G. Herreshoff. His productivity was extraordinary, and his body of work included a high percentage of the most successful racing yachts of his time. Burgess attended Harvard University, and although his education touched on engineering, he did not graduate. His work experience combining engineering and aircraft design, however, proved an ideal foundation for innovation including, occasionally, extreme rule-beating racing yachts. Among his early designs was the 52′ “cantilevered” scow sloop OUTLOOK, which had 31′ of overhangs and spread 1,800 sq ft of sail—a masterpiece of engineering, but an impractical freak pointing out that a new approach to rating rules was needed. Herreshoff created the Universal Rule soon after.

Burgess designed many early powerboats (including a boat that held the world speed record for a while) and a number of successful R- and Q-class sloops under the Universal Rule. He drew many one-design classes, some Six-Meters, and a number of commercial vessels. He also co-owned an aircraft company for a time, and he worked with Wilbur Wright to build several airplanes.

Working for a short time in partnership with designers Frank Paine and A. Loring Swasey, with L. Francis Herreshoff and Norman Skene on the payroll, he helped to create several Gloucester fishing schooners for prospective races against their Canadian counterparts, and a number of Universal Rule and International Rule yachts. Many more racing yachts and one-design classes, including the Atlantic class, followed the dissolution of this partnership.

Burgess’s most famous design is probably the 58’10” staysail schooner NIÑA, which won the Fastnet Race in 1928 and, a remarkable 34 years later, the Bermuda Race of 1962.

Burgess designed the J-class AMERICA’s Cup defenders ENTERPRISE and RAINBOW, and, working with a young Olin Stephens, created the 1937 defender RANGER.

(A profile of Burgess appeared in WoodenBoat Nos. 71, 72, 73, and 74. Burgess’s plans and papers reside at the Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library, Mystic Seaport.)

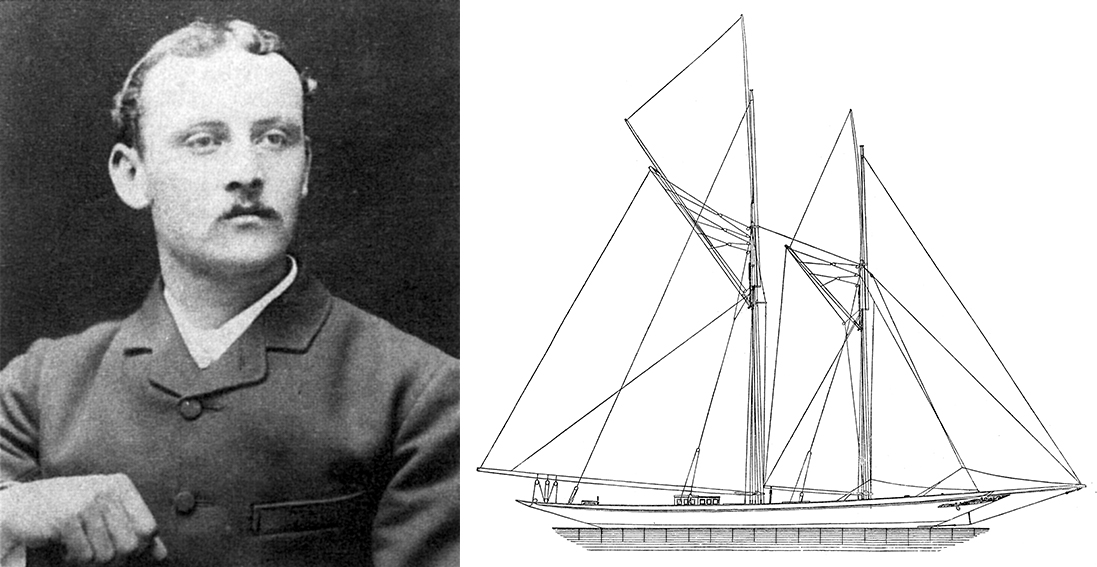

William Fife III

1857–1944, Fairlie, Scotland

Large and elegant—and fast—sailing yachts were William Fife III’s specialty. His CICELY, at right, was 134′ LOA.

Scottish designers and boatbuilders William Fife and William Fife II were notable in their own right, but William Fife III turned out to be the most remarkable of the Fife dynasty. His emphasis was on scientific design and engineering practices to a greater extent than his father’s and grandfather’s had been. An occasional rival of N.G. Herreshoff, he was seldom able to beat him—it was an excellent engineer against an engineering genius. Nonetheless, he enjoyed a lifetime of success on his side of the Atlantic. He designed over 800 yachts in the course of a 60-year career. While Herreshoff was sometimes accused by his contemporaries of having sacrificed beauty for speed (an idea not often voiced today), it is said that Fife never created a yacht that was not first and foremost a work of art.

Like his American rival, Fife ran what was probably the best yacht-building yard in his country. His yachts have always been admired, and were well-engineered structures carefully built of excellent materials, so many have survived, have been restored, and often compete in today’s classic yacht regattas. Most are easily recognized from the distinctive dragon cove stripe that became a Fife trademark after 1889.

Fife designed his first boat, the 28′ cutter CLIO in 1875, at age 19. In 1888, he gained an international reputation when the cutter MINER VA began to race in the United States, beating every boat for two years. Essentially a cruising boat of moderate design created without regard to any rule, she helped to point out that more wholesome types could perform better than the deep, narrow “plank-on-edge” cutters that were especially popular in Europe at the time.

Fife helped to create the International Rule and designed many yachts under it, ranging from Six-Meter sloops up to enormous 23-Meter sloops that were the International Rule’s equivalent to the Universal Rule’s J-class AMER ICA’s Cup defenders. His success in Six-Meters caused some to call it “the Fife class.”

Fife designed Sir Thomas Lipton’s 1899 AMERICA’s Cup challenger SHAMROCK, and later, SHAMROCK III.

In 1926, Fife designed the marconi-rigged cutter HALLOWE’EN , which, like Olin Stephens’ DORADE in the United States, served to introduce yachts of more modern proportions to ocean racing. She set a course record in the Fastnet Race that stood for many years.

(A profile of Fife appeared in WoodenBoat No. 90; see also Fast and Bonnie, by May Fife McCallum, and William Fife, by Franco Pace. Fife’s surviving archives are held by Fairlie Restorations in Hamble, England.)

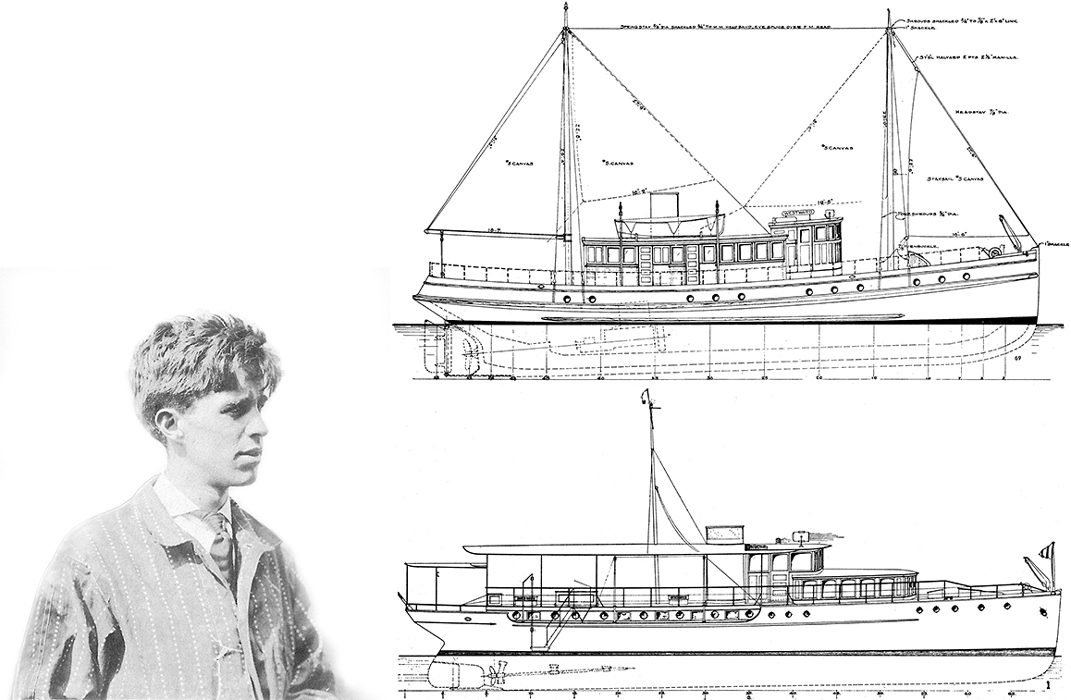

Leslie Edward “Ted” Geary

1885–1960, Seattle, Washington

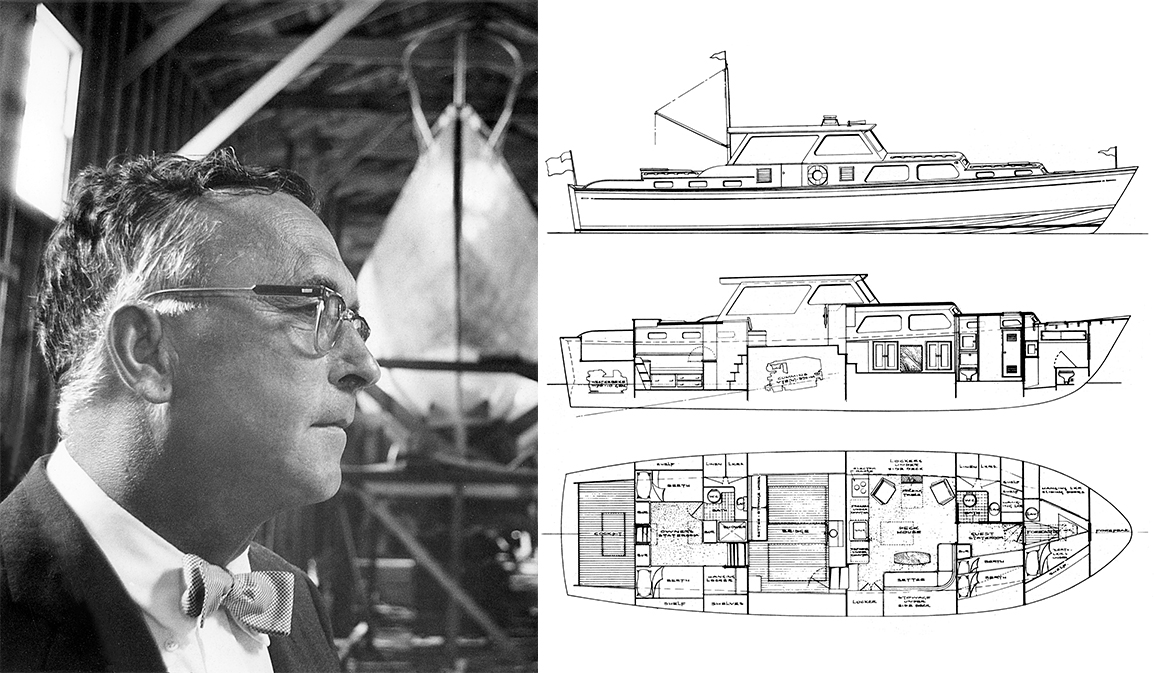

Ted Geary began designing sailboats at a young age, but arguably his large poweryachts represent his most memorable work. At right are two notable examples, both from 1924. Top right is GOSLING, 75’, built at Lake Union Dry Dock in Seattle and delivered to California on her maiden voyage. The 86’ WESTWARD, bottom right, originally used for hunting and fishing expeditions, is still voyaging today on her original Atlas engine.

Ted Geary designed his first boat, a successful 24′ racing sloop, at age 14. He showed so much promise that a group of local businessmen paid for his education at MIT. After graduating, he immediately began work as an independent designer (skipping what was typically a multi-year apprenticeship), and repaid his benefactors while designing a series of fast, luxurious commuter yachts for Puget Sound.

The majority of his work was in power craft, which included the famous 45′ “Lake Union Dreamboat.” Most of his powerboat work was in the 80′ to 150′ range, and included many rugged, fuel-efficient luxury yachts capable of both coastal cruising and transoceanic travel. Among these, probably the best known are the 96 footers PRINCIPIA, BLUE PETER, ELECTRA, and CANIM, all still in use today.

Geary was an accomplished racing skipper starting in his teens and continuing throughout his life. He won many races in boats of his own design, which undoubtedly greatly advanced his career. At age 20, he drew an improved version of his first design, which was never defeated. In 1913 he designed the Universal Rule R-class sloop SIR TOM, which raced almost unbeaten throughout the West Coast, holding the Pacific Northwest title for 14 years and competing successfully against Canadian rivals in the Lipton Cup series year after year. In 1928, Geary sent SIR TOM’s plans to his Canadian opponents, in the interest of the sport. A very similar boat beat SIR TOM in the next series, but the previous pattern reasserted itself the next time.

In the 1920s, Geary designed a series of successful racing and cruising schooners. Still sailing today on the West Coast are the 60′ RED JACKET and the 57′ SUVA.

Geary, however, was not just a large-yacht designer. He designed the still popular one-design Geary 18 for use by local youth sailing programs, which he actively supported, and he even designed a “pond yacht” model for local competition.

(A profile of Geary appears in WoodenBoat Nos. 137 and 138. His surviving papers are in private hands.)

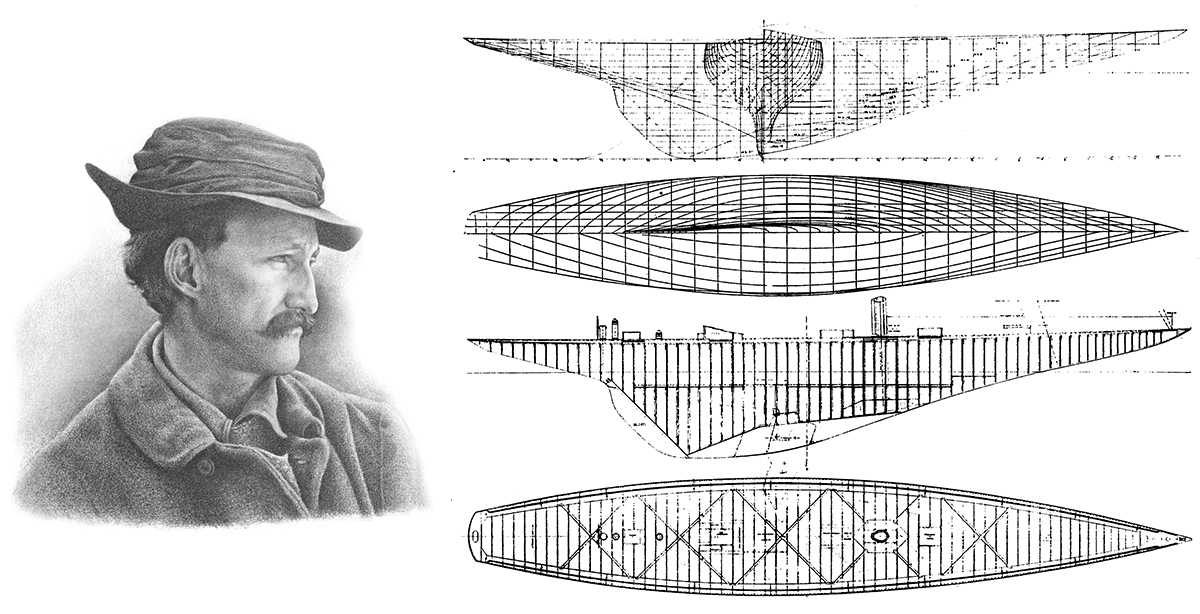

Charles Raymond Hunt

1908–1978, Boston, Massachusetts

C. Raymond Hunt is best known to sailors for his Concordia sloops and yawls, but among poweryacht aficionados, his innovations in power cruiser design made him a favorite. The deep-V hulled STING RAY V is at right.

Although C. Raymond Hunt didn’t design as many boats as the other men in this article, his work was remarkably diverse and had tremendous influence.

The best known of his sailboats are the Concordia 39 and 41, which many consider to be the most perfect expressions of the CCA Rule. A 39 was the smallest boat ever to win the Bermuda Race, in 1954, a feat repeated in 1978. Hunt’s own Concordia 41, HARRIER, with his family as crew, won all six races in the British Cowes Week of 1955.

Hunt also designed the popular 110 class, a 24′, double-ended, fin keel, one-design sloop of plywood with rectangular sections and vertical stem, sternpost, and topsides. Larger variations were the 210, 410, and 510, which illustrated one practical configuration for light-displacement sailboats uninfluenced by any handicapping rule.

Hunt designed several successful 5.5-Meters and the 12-Meter EASTERNER, a candidate for the 1958 AMERICA’s Cup defense, later campaigned more successfully in ocean races as NEWSBOY.

It is in powerboat design, however, that Hunt made his most significant innovations. During World War II, he worked to improve rough-water performance of destroyers by combining a hard-chined hull with underwater sections resembling an inverted bell shape. Though not adopted during the war, the “Huntform” hull re emerged in Hunt’s design for a scow-like outboard boat, which became the Boston Whaler, the most popular production outboard boat ever built.

Later, Hunt developed the deep-V hullform, which dispersed wave impacts to allow powerboats to maintain high speeds in rough water. The first production boat of the type was the Bertram 31, of which more than 1,860 were built. The deep-V continues to be very popular in the powerboat industry.

(C. Raymond Hunt’s plans reside at C. Raymond Hunt Associates in New Bedford, Massachusetts. For designer Joel White’s review of STING RAY V, see WoodenBoat No. 98.)

Phillip Leonard Rhodes

1895–1974, New York, New York

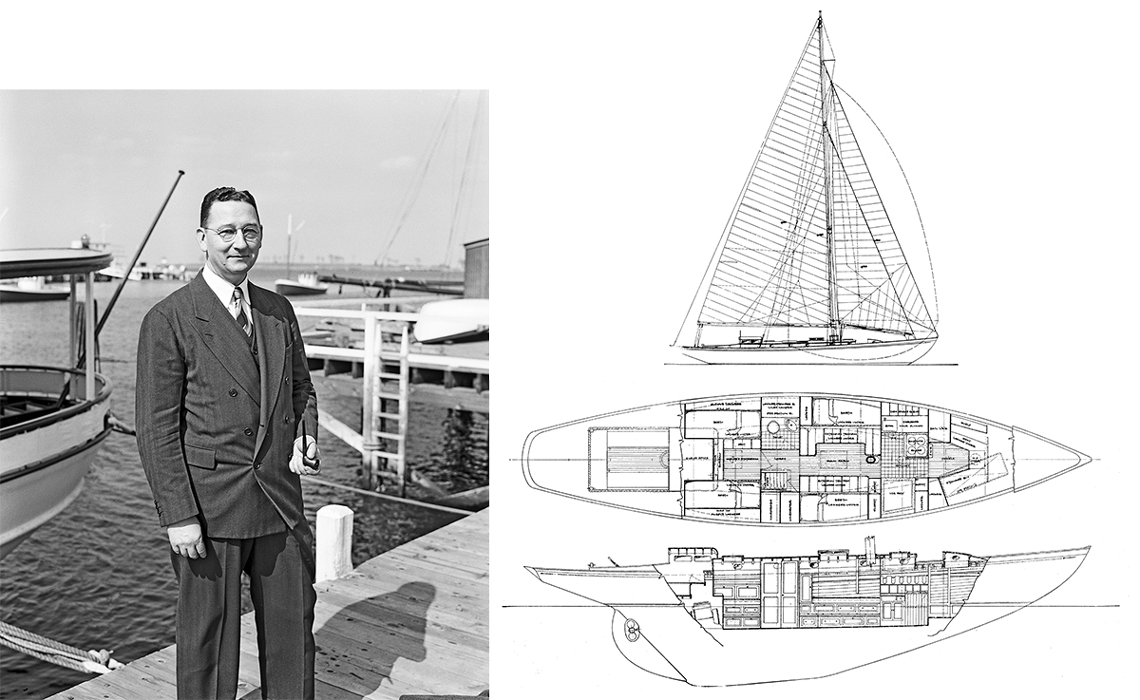

Philip Rhodes was an MIT-educated yacht designer whose far-ranging work included one-design racing boats and the AMERICA’s Cup defender WEATHERLY. The 53’ KIRAWAN, at right, won the 1936 Bermuda Race and is still sailing today.

Phil Rhodes had a gift for the dramatic and elegant line, and he understood that every line of a design had an influence on aesthetics. He was a master of harmony—all the lines of the hull, deck structures, and rig were created with a relationship to every other line.

After graduating from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1918, he designed fast motorboats and worked with Alexander Graham Bell to develop hydrofoils. He opened his own design office in 1925.

Rhodes helped create the CCA rating rule, which advocated ocean-racing designs that would also be excellent cruising boats. Rhodes’s most famous designs were of the keel-centerboard type that the rule encouraged, starting with the 46′ yawl AYESHA, around 1930, and finding its ultimate form in 1955 with CARINA II, a 53-footer that won two transatlantic races, two Fastnet races, and the Bermuda Race, among many others. Other well-known ocean racers include KIRAWAN, CARIBBEE, ESCAPADE, HOTHER, and THUNDERHEAD.

The only yacht that Rhodes drew to the International Rule was the 12-Meter WEATHERLY, which defended the AMERICA’s Cup in 1962.

Rhodes also designed steel-hulled motorsailers in the 70′ to 100′ range, featuring beautiful, long-ended keel-centerboard hulls combined with relatively large superstructures. One of them, TAMARIS of 1938, is said to have been the first welded steel yacht.

His one-design classes include the Penguin, with over 10,000 boats built, and the Rhodes 18, 19, and 22. He also designed what are still regarded as some of the most appealing cruising boats constructed in fiberglass, including the 40′ Bounty II, 33′ Swiftsure, Ranger 28, Rhodes Meridian, Pearson Vanguard, Cheoy Lee Rhodes Reliant, and O’Day Tempest and Outlaw

(See also Philip L. Rhodes and His Yacht Designs, by Richard Henderson. Rhodes’s plans reside at the Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library, Mystic Seaport.)

Olin Stephens

1908–2008, New York, New York

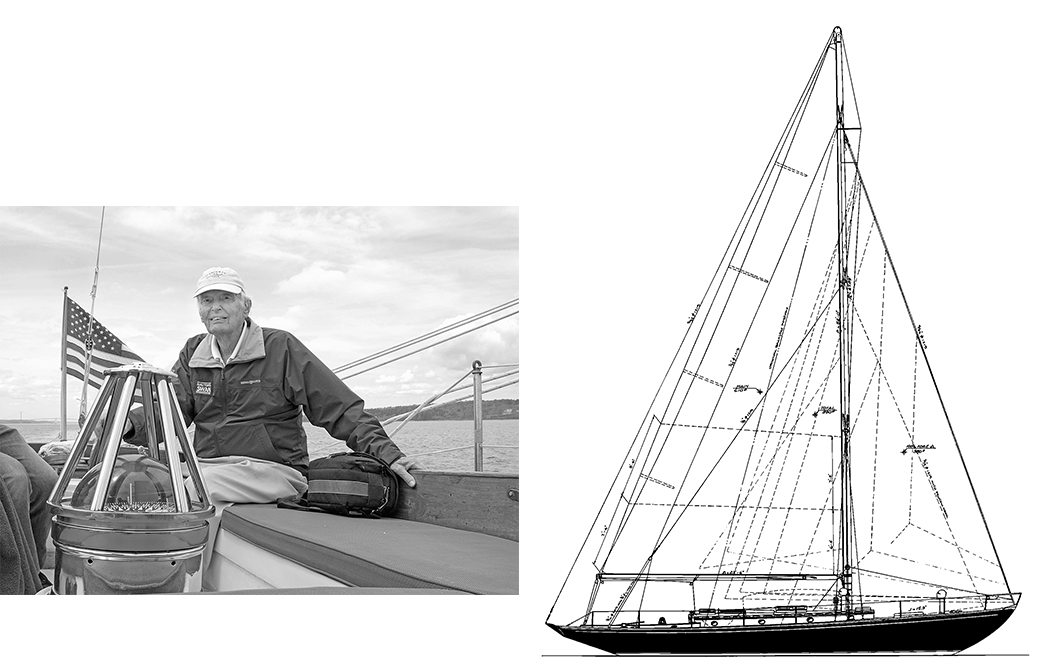

Olin Stephens had an illustrious yacht design career that spanned much of the 20th century, yet he never lost the joy of having his hand on a tiller, as here in 2007 at the age of 99 aboard FALCON, one of his New York 32s, also shown at left.

One of yacht design’s universally acknowledged masters, Olin Stephens, though largely self-taught, used a scientific approach to a greater extent than most of his peers, eventually helping to develop procedures for tank-testing of models and, later, computer simulations. He and Drake Sparkman formed Sparkman & Stephens Inc. in 1929, and their first commission was the 21′ Manhasset Bay One-Design. Next came two Six Meters, following the International Rule, which formed worldwide conventions for racing yacht design and measurement. Boats designed under this rule have the word “meter” in the rating, but that reflects the formula used, not their length. Stephens’s fourth design was the 52′ marconi yawl DORADE, which for the first time incorporated into an ocean racer the narrow beam, deep draft, relatively light construction, and outside ballast of International Rule boats. In 1931, DORADE won the Transatlantic Race and the Fastnet Race.

With W. Starling Burgess, Stephens designed the J-class RANGER, which defended the AMERICA’s Cup in 1937. His 12-Meters defended the Cup in eight of nine matches between 1958 and 1980. Two of his Six-Meters won gold medals in the Olympics of 1948 and 1952. Although he disapproved of the comparatively low stability of keel-centerboarders, which were encouraged by the CCA rating rule, his design FINISTERRE, a 38-footer of that type, won many races, including three consecutive Bermuda Races in 1956, 1958, and 1960. Keel centerboarders combined a keel of moderate depth, which permitted shoal-water cruising, with a centerboard set deep in the keel, which improved windward sailing performance. Among his one-designs were the Lightning (19′), Blue Jay (13′ 6″), Interclub Dinghy (11′ 6″), Shields class (30′ 21/2″), and the New York 32 (45′ 4″). Sparkman & Stephens produced over 2,000 designs during Stephens’s lifetime.

Stephens was an outspoken advocate of safety in the design of offshore yachts, and did much to help develop improved handicapping systems culminating in the International Measurement System, which was the first popular rule using computers to analyze entire designs, as opposed to just a series of measurements.

(A profile of Stephens appeared in WoodenBoat No. 98. See also Lines: A Half Century of Design and All This and Sailing, Too, both by Olin Stephens; and Sparkman & Stephens by Franco Pace. His plans reside at the Daniel S. Gregory Ships Plans Library, Mystic Seaport.)

Dan MacNaughton is co-editor, with Lucia Del Sol Knight, of The Encyclopedia of Yacht Designers. He currently works as a finisher at Artisan Boatworks in Rockport, Maine, and is a frequent contributor to WoodenBoat.