Getting Started With Boating Safety Equipment

“A man who is not afraid of the sea will soon be drowned, he said, for he will be going out on a day he shouldn’t. But we do be afraid of the sea and we do only be drownded now and again.” — John Millington Synge

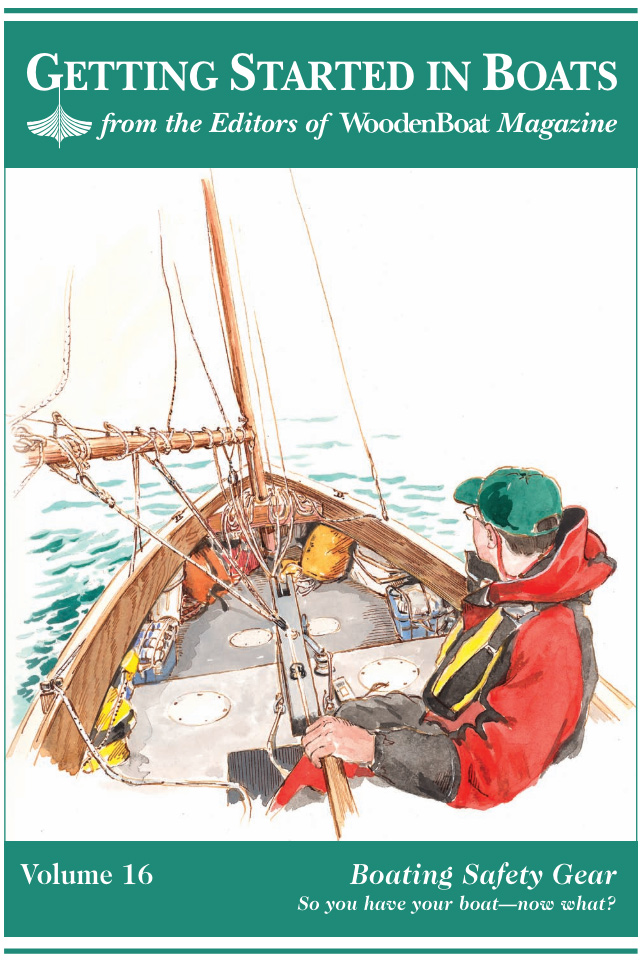

A boat is a magic carpet. No matter how small, a boat can carry you to remarkable places. But if you’re new to boating, you have a lot to learn. What do you need to carry on your person? How do you outfit your boat? What do you need to know? Here at WoodenBoat we have an annual event called the Small Reach Regatta, created by WoodenBoat’s senior editor, Tom Jackson, and some of his friends (like yours truly). To make this event a safe and fun time for everyone, we have developed the following list of safety items that are required to be on board each boat during the regatta.

Boat Safety Equipment Checklist

- Personal flotation devices (PFDs) for all crew

- Flotation, permanent or temporary

- Emergency kit including flares, horn, and first-aid supplies

- Timepiece

- Waterproof VHF radio, to be worn on the skipper’s person

- Foul-weather gear for each person aboard

- Water and food for the day

- Additional warm clothing stored in dry bags

- At least one anchor and rode

- Substantial bailing buckets

- Charts suitable for navigation

- Compass

- Line suitable for being towed

Click here for a downloadable and printable checklist

Whether or not you are able to join us for the Small Reach Regatta, the equipment above should help you to prepare for good times out on the water. Along with our Small Reach Regatta list, I have included some of my own thoughts about safety equipment and the basics of seamanship.

I encourage you to use this article as a guide to outfitting yourself and your own small boat, whether you plan to poke around on familiar waters or are venturing far from home. While the scope of this article is limited to small sailing and rowing craft, the information also applies to small powerboats. If you have a powerboat, be sure to look for additional materials, especially regarding power systems. Being safe is the first and most important step toward developing lifelong habits that make these adventures enjoyable. And, after all, enjoyment is the point of boating.

Rules, Regulations and What Safety Equipment Is Required on a Boat

According to the law, equipment requirements for a small sailboat or rowboat are minimal. A readily accessible Coast Guard–approved personal flotation device (PFD) for everyone aboard must be carried, along with a light (or lights) for nighttime operation.

If you select an inflatable (Type V) PFD, it must be worn, not just carried. If you take it off, you are not in compliance. If the boat is over 16’—and not a canoe or kayak—a throwable PFD like a cushion or life ring must be added. The proliferation of kayaks and small sailboats has created wide choices in PFDs. Except for their added cost, there is no reason not to get one that can be worn all the time, what the Coast Guard calls a Type III (non-inflatable) or a Type V (inflatable). For a Type III, make sure it is comfortable and has pockets, as many pockets as legally allowed.

If you operate at night, you’ll be required to carry lights and signaling devices. To be legal, you’ll need three flares or other night-marking devices. Again, a boat that is longer than 16′ becomes more complex; with such a boat you’ll need to carry three signaling devices for day as well, or, have three combination day/night signals.

Rowboats, kayaks, or sailboats under sail that are smaller than 7 meters and slower than 7 knots need a white light or a flashlight that can be shown in time to prevent a collision.

Once you cover what the law requires, there is a wide gulf between what you must carry and what you should carry.

Outfitting the Boat

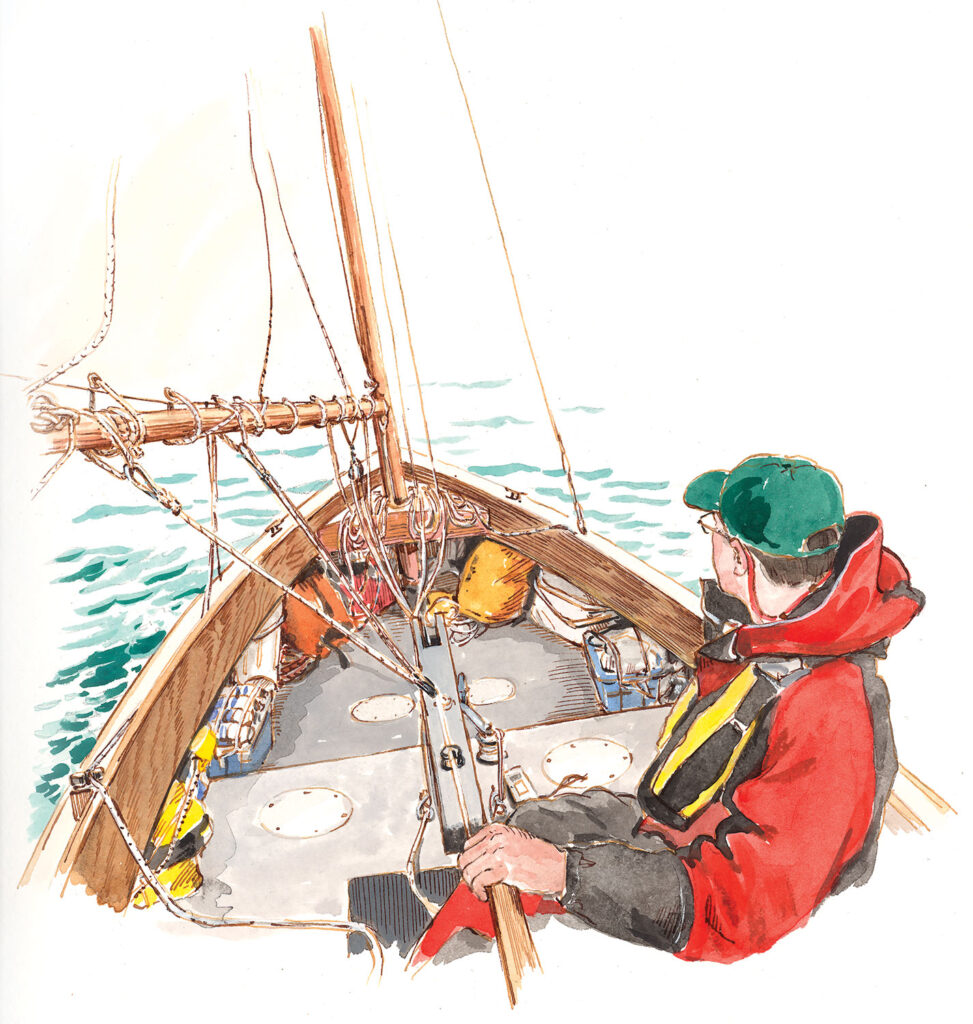

Mariners need to be orderly. Out on the water, when you need something, you often don’t have much time to look for it. The adage “A place for everything and everything in its place” applies. Gear should be tied into (or onto) your boat, especially on a small sailboat, because if anything goes overboard, that’s likely where it will stay.

With larger boats, a lot of gear, like buckets, a bilge pump, extra line, even a boarding ladder, can remain on board. But small boats must be loaded prior to every launch. I like to think of the gear in terms of bags or packs. For a kayak or a canoe heading out on a one-day trip, all the gear can live in a single bag. For a trailered boat and/or a longer voyage, several bags might be needed. I have found it easiest to organize gear in groups, categorized according to use, so that all I need to do is grab the right bags and be ready to go. Also, on any rowing trip that is more than around a harbor, I carry an extra pair of oars and an extra oarlock (all of which are tied to the boat with lanyards).

And, be sure to carry a tool/repair kit with spare line, a multitool, some zip ties, and perhaps a few spare blocks and shackles. Also, be sure to bring some spare parts, especially a spare drain plug.

Anchors

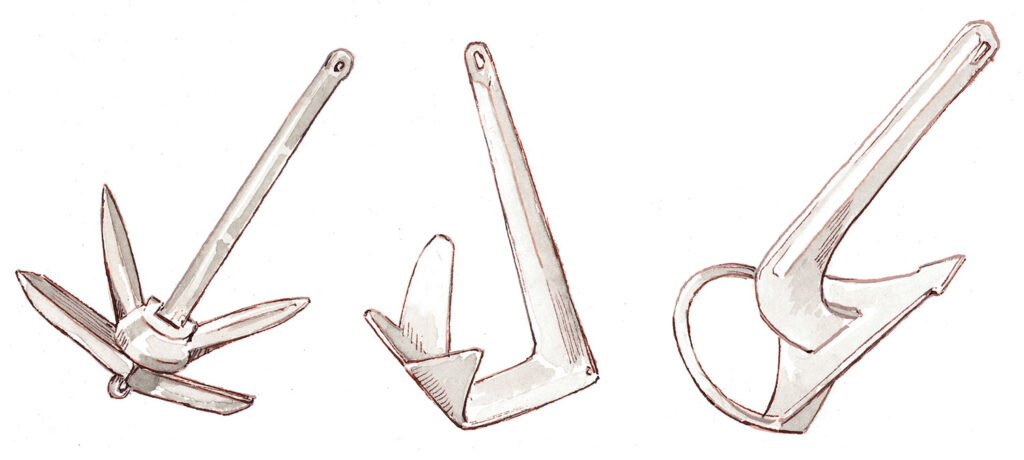

Keeping your boat where you want her could require as many as three anchors: a light one at the stern for beaching, a grapnel anchor at the bow to hook to the beach, and a larger anchor (usually a Danforth, as seen in the illustration on the facing page) for real anchoring.

For relatively small boats (around 16′ or smaller), Danforths or Danforth types in the 8 lb. range work well with 6′ of chain and 150′ or so of 3⁄8″ rode (anchor line, attached to the chain). These are easy to handle, so it doesn’t make sense to go smaller. If you routinely cruise in shallower water, you can have a shorter rode, but since these lightweight anchors work best if given a 7:1 scope, I like to be ready for water depths up to 20′.

You should also have a painter (a line, permanently attached to the bow), some fenders, and at least a stern line.

On a small boat, stowing anchors so that they are out of the way can be a challenge. The Danforth style is flat and relatively easy to handle and to stow. A folding grapnel (which looks a little like a small squid) can also be handy as a second anchor for beaching. Both claw- and plow-style anchors (two well-named configurations) are very difficult to stow. Large canvas bags, called carryalls or ice bags work well for anchor stowage.

These should be large enough to handle the rode and chain as well as the anchor itself. A lanyard attached to the handles closes the bag, and enables it to be lashed vertically against the side of the boat. To protect the boat, I line my bag’s bottom with a piece of Ethafoam (which doesn’t absorb water), although if the anchor is habitually placed on top of the rode, it will provide the necessary cushioning. I have also used buckets to hold the rode and chain, but generally the anchor will not fit a bucket as well as it does in a bag.

Image of a Folding Grapnel Anchor, Claw Anchor, and Plow Anchor

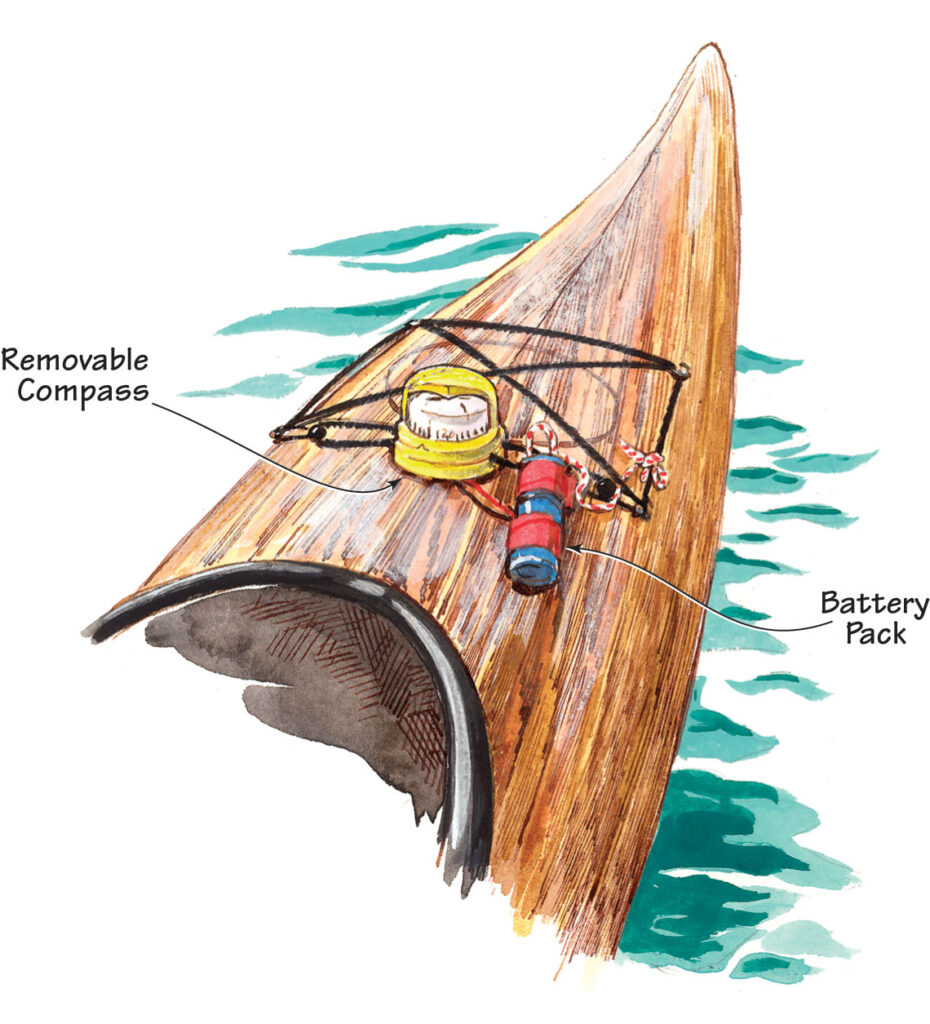

Compass

Mount your compass in an easily visible spot. For small boats without fixed-mount compasses, there are a number of removable compasses on the market.

Flotation and Bailing

If the boat swamps or nearly swamps, the boat bucket is the first thing you reach for to get rid of the water fast. On a larger boat, I like to have two: a 5-gallon drywall bucket that also can be used to carry and stow stuff, and a smaller, rubber agricultural bucket. Remove the metal handles and replace them with rope. Into the boat bucket goes at least one scoop bailer, either one made from a cutaway plastic jug, or a wood-and-leather bailer that will stay afloat if you drop it overboard.

A portable pump with attached hose completes the bailing kit. It’s not a bad idea to know what it’s like to bail out your water-filled boat, especially if it’s a small open sailboat, which has a higher probability of swamping than other types. If you decide to do a swamp-and-bail test and find that there is not enough flotation to allow you to safely bail the boat, you can add more.

Outfitting the Operator

Personal Flotation Device (PFD)

First and foremost, upgrade all of your PFDs so that each one has a loud whistle. (A horn or whistle for the boat itself is also highly recommended.) You’ll also need a timepiece for navigation and, if you are running at night, a small flashlight or headlamp.

On a very small boat, some of your gear will need to be stowed in your PFD. Kayakers usually carry signals, a radio, some food, tools, flares and a flashlight, as well as repair gear in the pockets of their PFDs.

Pack food and water for each trip. Depending on the climate, a thermos of hot tea or other drink (my current favorite is a Chinese ginger drink) can improve your worldview.

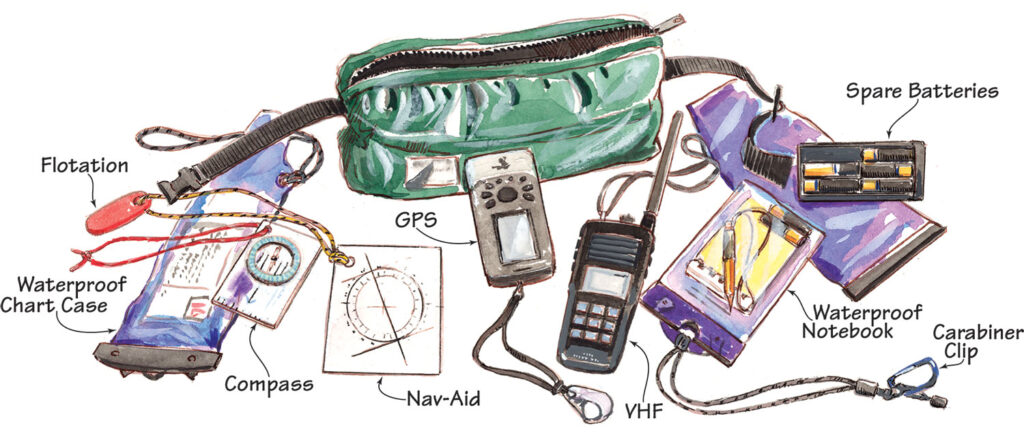

Navigation Bag

My communications/navigation bag is a simple waist bag. Here, I begin by packing a rolled chart (needed for the day) in a waterproof case. These should be resilient enough to stand up to salt air but clear so that you can read a chart through it. Depending upon the size of the chart, the chart case may fit into the nav-bag. Charts that are reasonably waterproof are now available, but putting charts in a case helps to keep them from blowing overboard or sinking when you drop them.

There are some navigation tools that can be adapted to work with these charts, as most waterproof charts are not to standard scales. Parallel rules and dividers don’t work well on a small boat, so a kayaker’s “Nav-Aid” or a backpacking compass can be used as a protractor, and if you mark a string with nautical miles based on your chart’s scale, you can instantly figure distances. Carry pencils to write down courses and distances in a waterproof notebook. Include a grease pencil in case you need to write on the chart case, or on a convenient place on your boat.

Personal stuff like sun block, spare spectacles, and a couple of high-energy food bars can also be found in my navigation bag. This, too, is where I carry a portable GPS and cell phone, two optional items. The GPS is hugely useful for navigating a small boat if used in conjunction with non-electronic tools. To improve reliability, both it and the cell phone go into waterproof bags. These will also float the instruments. A cell phone can be useful but does not substitute for a VHF on the water, since it isn’t monitored by other boats or by the Coast Guard.

I also like to keep my “waterproof” handheld VHF in a waterproof bag for extra protection, and there is usually space for spare batteries (or a loaded battery tray, if you use a rechargeable VHF). I keep this in my nav-bag unless I am in heavy weather. In those conditions, I wear the VHF around my neck or put it in a pocket of my PFD.

First-Aid and Emergency Equipment

For boat use, a first-aid kit has to be contained in a waterproof box. I like a product called Mini Medical Kit because it’s small enough to fit into a small, waterproof pouch which goes into a PFD pocket and is quickly available. It’s nice if the kit includes equipment to fix cuts and scrapes, moleskin (for blisters), and even a CPR mask (if you’ve completed a CPR course). I like to carry the Wilderness Medical Associates Field Guide along with SOAP notes (Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan).

If there’s a risk of an unexpected overnight, remember that plastic tarps or garbage bags can be used for emergency shelter. I also keep a separate waterproof pack of three day/night flares, and a large, waterproof flashlight.

In foggy country like Maine, a mouth-operated foghorn and, perhaps, a radar reflector can get tucked in as well—both tied to the boat by a lanyard.

Crew Considerations

Cold, wet people don’t perform well. A dry bag with a change of clothing (minimally, fleece that would fit the largest person on board), a wool or fleece hat, and a windbreaker should be aboard. Ideally, each person will bring his or her own clothing bag containing foul-weather gear.

Warm, dry feet are a blessing, and boots or other footwear that keep your feet dry — or warms them up fast after they get wet — can be important.

Most of this can be packed so as not have to require repacking for each trip. But things that do get wet — especially navigation gear, clothing, and PFDs — should be rinsed in fresh water after each trip if you want it to last.

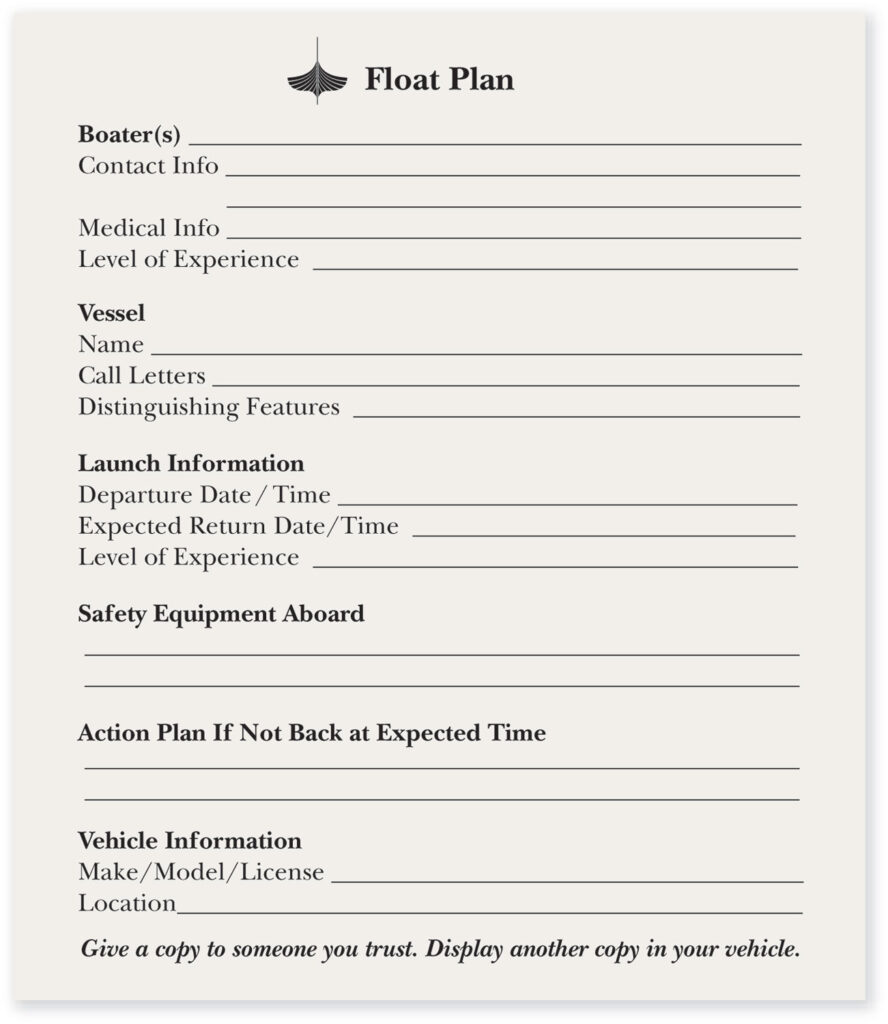

File a Float Plan

Although with good seamanship and the right gear, the emergency parts of a float plan may never be needed. But filing one with someone you trust so that he or she knows where you are going is a good idea. A float plan lists who is on the trip, important contact and medical information, a description of the boat or boats, your intended route, destination, time of departure and expected time of return, what’s on board, plus vehicle information.

Click here for a downloadable and printable Float Plan

Bon Voyage

Boat safety gear is worthless without the knowledge to use it. Because most seamanship books are aimed at operators of larger craft, perhaps a better place to turn for guidance on gear use, navigation, weather, and clothing is kayaking literature. The gear you carry will help you have fun—and return home safely.

Ben Fuller, curator of the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine, has been messing around in small boats for a long time. He is a Master Maine Sea Kayak Guide, open water kayak instructor, and is still learning.