Sailing Rigs: A Beginner’s Guide

Many types of sailing rigs have developed over the centuries. They range from rigs for large oceangoing vessels to those for small boats designed for gunkholing in sheltered waters. Although the description of a given rig type holds true no matter what size boat, our focus and discussion will be on small boats that can easily be rigged for daysailing. A small boat, rigged simply, will take you away from the hustle and bustle of modern life in a single afternoon…and make you feel as if you had sailed on a deep-sea voyage.

On the following pages, we examine 12 rigs for small boats—and their virtues and vices.

Sailboat Dynamics

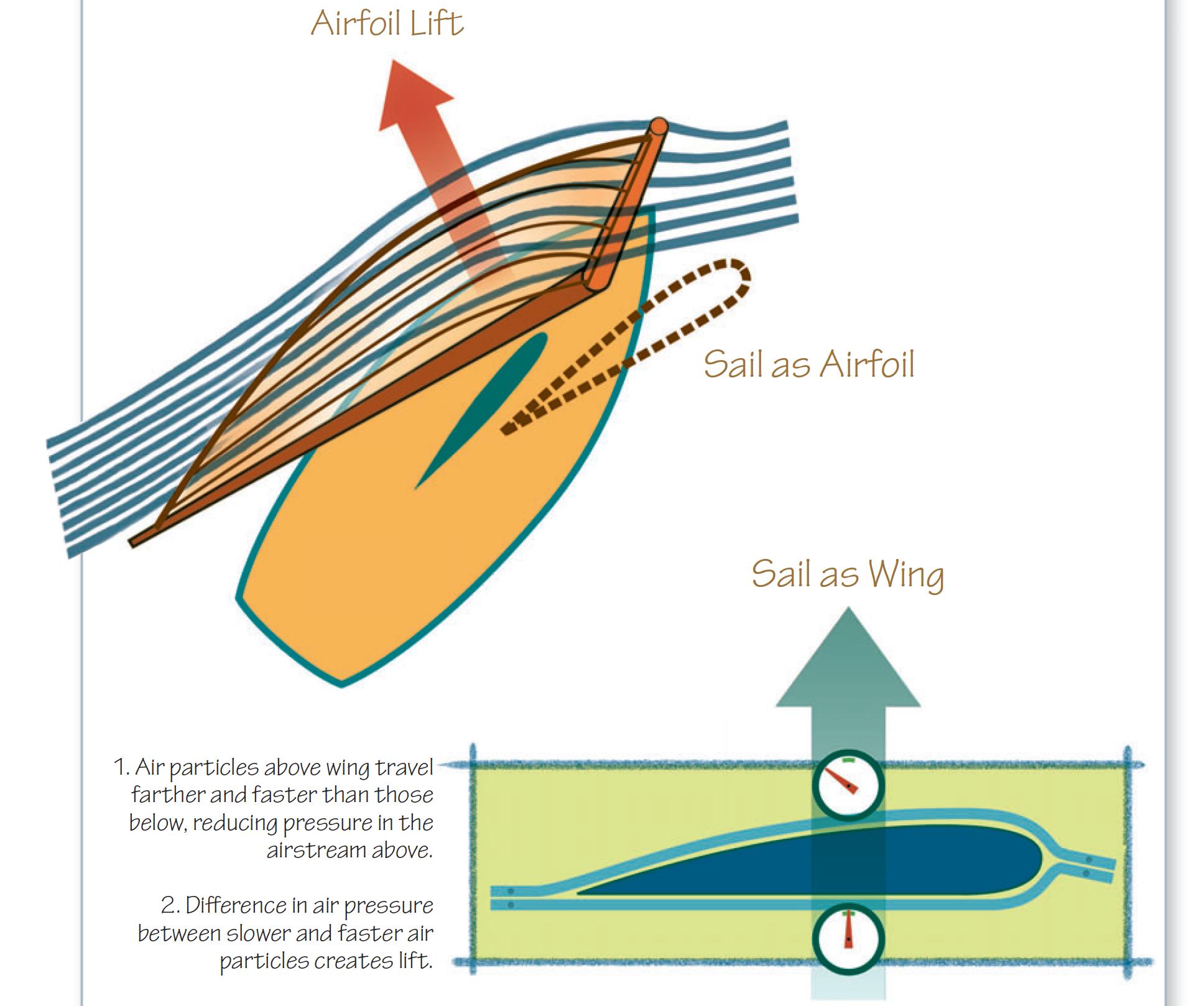

Let’s consider how a sail makes a boat move through the water. Running with the wind makes intuitive sense: you put up the sails and the boat is pushed along like a tumbleweed. The world’s first sails worked on this principle: they were simple squaresails attached to simple masts, and they were pushed downwind.

Modern sails are not merely flat pieces of fabric that function on this pushing principle; they have shape built into them. The reason a boat can sail close to the direction from which the wind blows is that its sails are shaped like the wing of a bird or airplane. This shape, when moved through the air (or, more accurately for a sail, when air moves over it), creates lift. But because the sail is positioned vertically on the boat, rather than horizontally as is an airplane wing, the result is forward motion rather than altitude. (There is considerable sideways force in this interaction of sails and wind, and that is counteracted by the boat’s centerboard or keel; that’s why the boat doesn’t slip sideways excessively.)

Small-Boat Sail Types

Lug Sail

The lug rig, once common on British working boats, has today fallen out of fashion on nearly all but small dinghies. However, in this role it has become extremely popular, and with good reason: it is simple, requires no standing rigging, performs well, and its short spars may be stowed onboard.

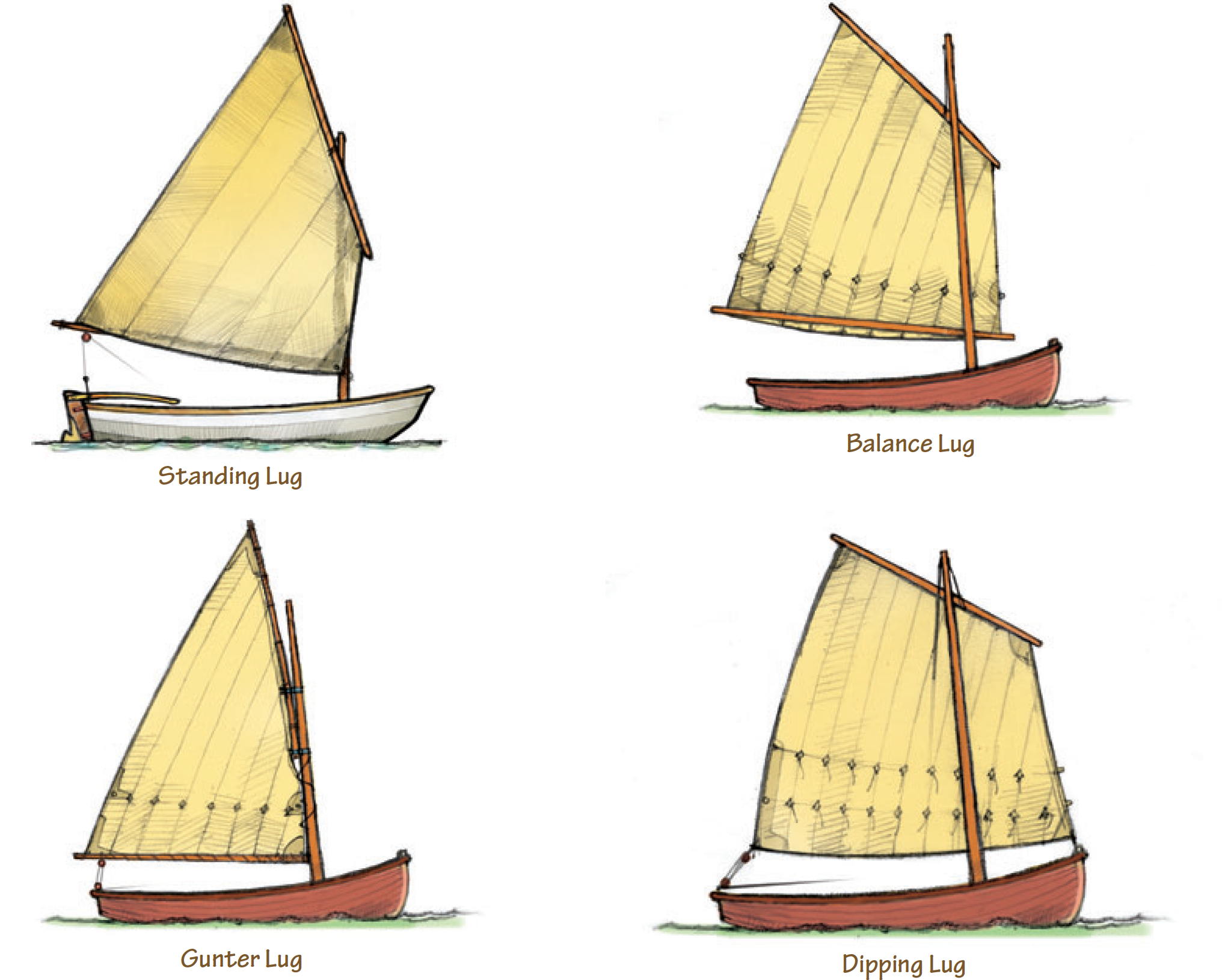

A four-sided sail, the lug has four variations: standing, balance, dipping, and gunter. In all four the mast is typically stepped well forward and the sail is controlled by a single halyard and a sheet; the head is laced to a yard and the luff is free-standing.

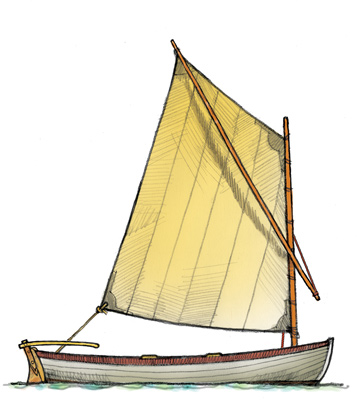

Standing Lug

The most popular of the four types is the standing lug, which can be set with or without a boom. The tack (lower forward corner) of the sail is belayed near the heel of the mast, and the sail’s head (its upper edge) is attached to a yard (a spar) at the top. The exact position at which to tie the halyard to the yard, and how high to raise the yard, are often found by trial and error but once established will remain constant. Once this sail is raised, its luff will be angled aft from top to bottom because the yard projects forward of the mast. The standing lug, because of its geometry, can be paired with a small jib.

Balance Lug

The balance lugsail is similar to the standing lug but is cut so that a small portion of both yard and boom—up to one-seventh of the length of the foot—are forward of the mast.

Gunter Lug

The gunter lug is also similar to the standing lug, but the yard is brought almost vertical, its heel kept aligned to the mast by jaws.

Dipping Lug

Most powerful of the four, but now least common, is the dipping lug. It does not use a boom and, even if large, needs only one halyard and generally no standing rigging. The yard is raised as in the standing lug, but it and the sail itself are always to leeward of the mast—the fall of the halyard, if belayed to the rail, does the work of a windward shroud—and the tack cringle is attached to a hook on the stemhead. When altering course from one tack to another, the sail has to be lowered, or “dipped,” from one side of the mast to the other and then raised again to leeward—an often-cumbersome maneuver that inevitably results in a loss of momentum.

Sprit Sail

The spritsail was once very common on small working boats but fell out of favor until a revival of interest took place in the 1960s. Like the lug, it is a simple rig that can be easily stowed onboard, and is thus ideal for a small boat.

The rig requires a mast and sprit, the latter never longer than the former, and the sail may be set with or without a boom. For a small sprit rig there is no call for standing rigging and, because the mast can be stepped easily by hand, there is no need for a halyard because the tack and throat are permanently lashed to the mast, which is stepped through the mast thwart. The upper end of the sprit is poked into a rope becket, or loop, at the peak of the sail, and once the mast is stepped, the sprit is pushed up and held there by passing its heel into a rope “snotter” or adjusting line, on the mast.

Unlike the lug rigs, sprit sails are not easy to reef and not always easy to single-hand in larger sail plans.

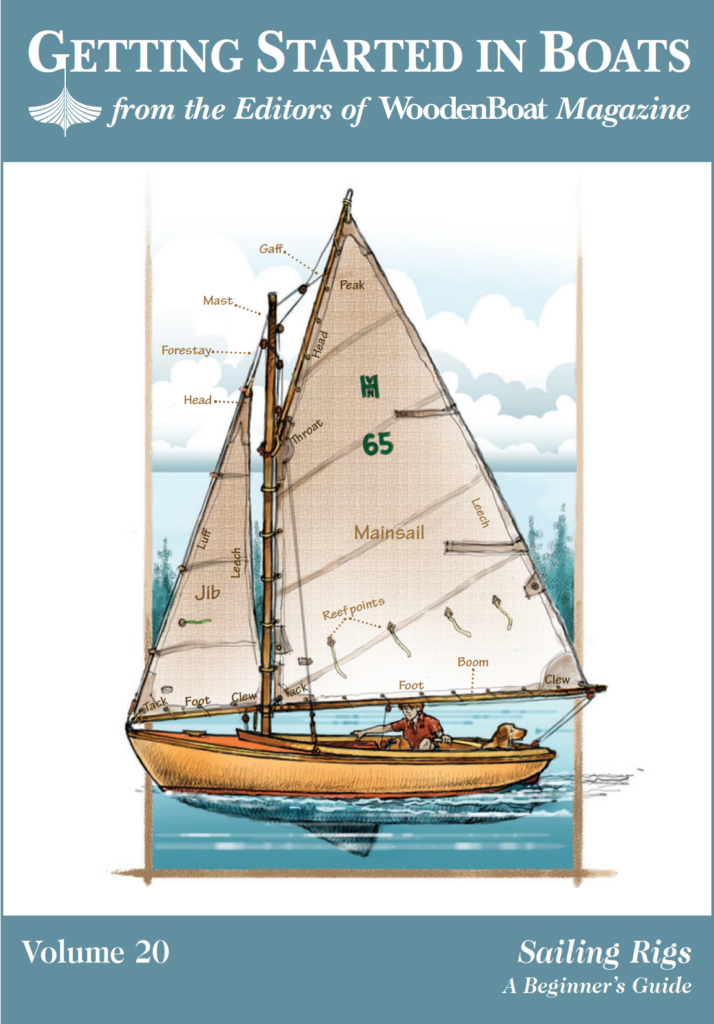

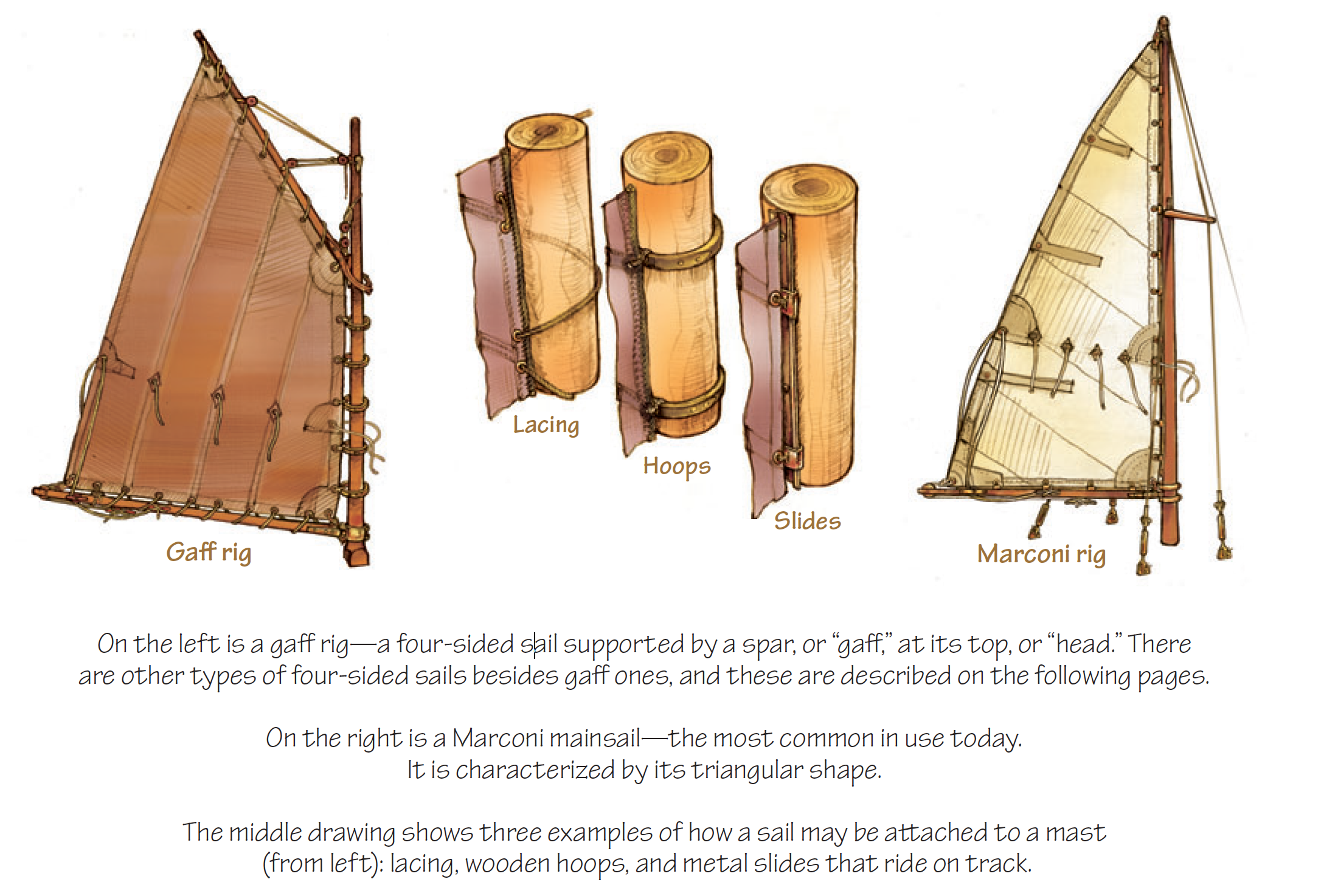

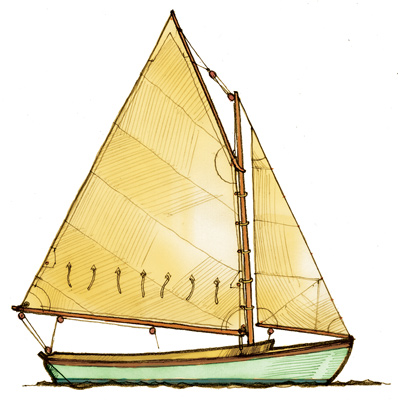

Gaff Sail

A gaff sail is four-sided, and is supported along its top and bottom edges by spars whose forward ends pivot on the mast to which the sail is attached. The top spar is called the gaff; the bottom one, the boom. In some cases, the boom may be eliminated.

The sail can be attached to the mast by hoops, lacing, or slides. On most boats the sail is attached to the boom and gaff by slides or lacing, but on some the sail is loose-footed and held to the boom only at its lower corners (the tack and clew.)

Gaff rigs were common on both workboats and yachts until the 1920s, when triangular-shaped marconi mainsails came onto the scene. In the decades following, the pointy-topped marconi rig eclipsed the gaff, and became conventional. This convention, however, has been challenged in recent years, as racing boats using the latest technology are designed with aerodynamically superior mainsails whose flat tops are supported by gaff-like battens. Traditional gaff rigs also remain popular today with some sailors, for it is powerful, easily handled, and good-looking.

The sail shown here is set on a catboat—long a favorite on the northeast coast of the United States. The rig is fundamentally simple: a single fore-and-aft sail set on a mast stepped as far forward as possible. While a catboat’s sail may be lug, marconi, or gaff, the latter has long been the most common. The sail can be easily reefed and is well suited to single-handing, but with the rig so far forward there can be a sometimes alarming tendency to “bury the bow” when sailing downwind in strong breeze.

Small-Boat Rig Types

Sloop

The sloop has a single mast that generally requires standing rigging (shrouds and stays) and sets more than one sail—most commonly a mainsail and one headsail (e.g., jib), although with the addition of a bowsprit, more than one headsail can be set.

For its mainsail a sloop may set a gaff, marconi, gunter, standing or balance lug, or sprit sail. It is an efficient rig to windward, but because of the standing rigging and multiple sails the up-front costs will likely be more, and it takes longer to set up. These last points are true of all the following rig types.

Schooner

Although unusual on a small boat, the schooner rig can be used. This rig has two or more masts, (for the common two-masted schooner) with the larger (the mainmast) nearest the stern and the foremast forward of it and shorter. It can be an interesting rig for a small boat. The illustration shows a cat schooner, so named because there are no headsails.

Cutter

Like the sloop, this rig has only one mast, but the mast is positioned farther aft than a sloop so that more than one headsail can be set without requiring a bowsprit. With its proportionally smaller mainsail, it offers more sail-reduction options in strong winds, although there are more ropes to pull. But be warned: On a small boat, more complication is not always good.

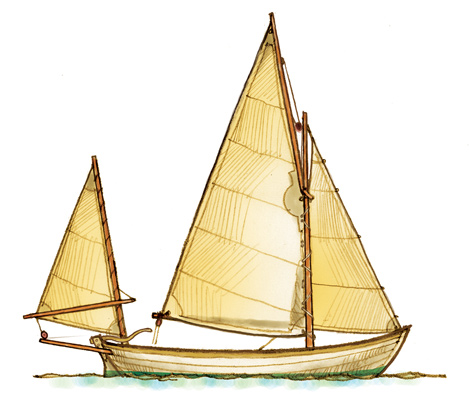

Yawl

The yawl is a two-masted rig with a small mizzen placed well aft (usually astern of the rudderstock, although in the case of the outboard rudder seen here this is all but impossible.) It can carry one or more headsails and offers a versatile sail plan, especially when shortening sail—if the mainsail is lowered, the sail area is markedly reduced but the boat remains well balanced under mizzen and headsail.

The yawl can be marconi, gaff, lug, or sprit, or it can set a different type of sail on each of its masts. Whether or not the rig requires standing rigging will depend on the size and height of the sail plan and the material used for the masts—the lighter and stronger the material, as with carbon fiber, the greater can be the sail area before standing rigging is required.

Some small boats sail well as yawls with two standing lugsails—a combination often seen on narrow double enders such as canoes, where the sailor cannot sit aft but is confined to the middle part of the boat. By stepping a mizzen well aft, a larger mainsail can be carried forward without damaging the rig’s balance. In this instance the typical rig will be low, unstayed, and without a headsail.

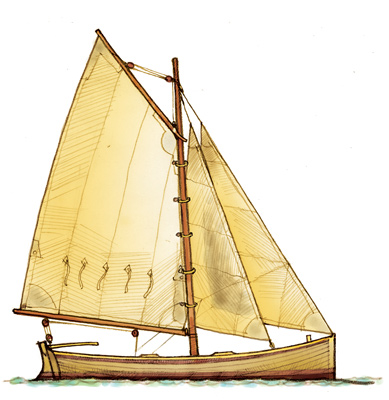

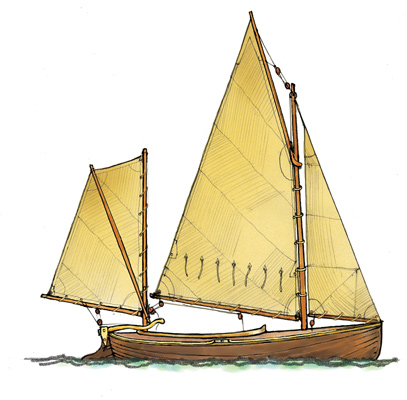

Ketch

Similar to the yawl, the ketch has two masts, but the mizzen is proportionally larger than a yawl’s and stepped farther forward. It can have multiple headsails and has similar pros and cons to the yawl. A small ketch rig can be unstayed, but even in small boats is often set up with standing rigging. In the example shown here, and in the yawl illustrated above, the tiller must have a sharp oval- or u-shaped bend built into it to accommodate the mizzen—or, the tiller may be eliminated entirely and replaced with a continuous loop of line.

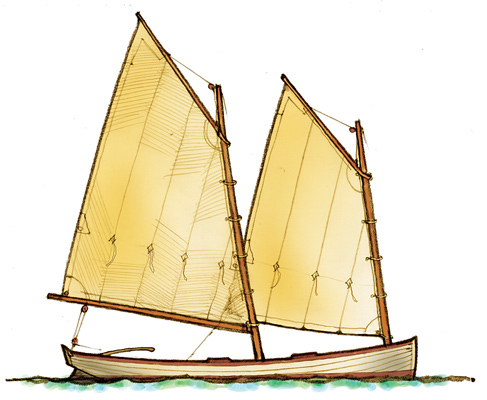

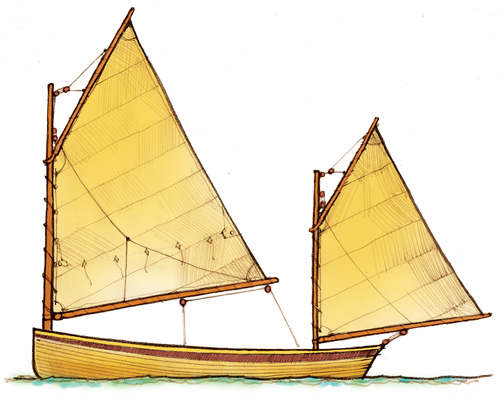

Cat-Ketch

This is a two-masted rig, but as the name “cat” suggests, the (larger) mainmast is set in the bow of the boat. Typically the masts are unstayed. Because there is more than one sail, the effort is spread along the length of the hull—which makes for easier steering in strong breezes.

Traditionally cat-ketches were small working craft operating from beaches; they are inexpensive, quick to rig, and can be single-handed. In more recent times cat-ketch rigs have been seen on small sailing canoes, sharpies, and larger cruisers. Cat-ketch sails can be marconi, gaff, lug, or sprit.

Sail Care

Sails are an investment: take good care of them. If your sails are to be left on board and bent onto the spars, remember to budget for sail covers—they are the sails’ sunscreen and well worth the expense. If your sails often get dunked in salt water, be sure to give them an occasional freshwater rinse. At the end of the season, use a scrub brush to wash your sails; it is important to get the salt out as it attracts mice and mildew. Bleach can be used to clean mildew but it can harm the fabric, so it is better to use a mild soap or cleaning agent. While washing your sails, inspect them for chafe and check that the stitching is still sound. And don’t be in a hurry to put your sails away; they need to be fully dry before being folded and stored.

Sailing is a lifelong endeavor, and there is much to learn. This basic overview of types, traits, and vernacular is intended to help as you contemplate which rig is best for your purposes. We offer it as your initiation—and your invitation—to the wonderful world of sailing.