Boats and kids go together like toes and sand. Building a boat with your kid(s) is a great way to start them off on a lifetime of maritime adventures. Kids learn patience, stick-to-itiveness, and specific hand–eye–mind skills. When my 10-year-old daughter, Ana, and I built the Salt Bay Skiff, I realized that parents could learn a lot from their kids, too.

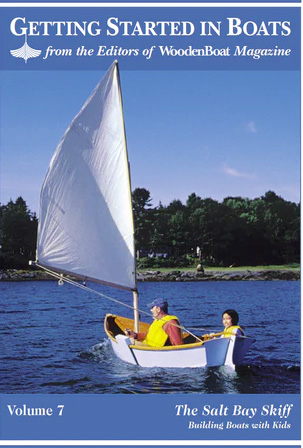

The Salt Bay Skiff has a graceful shape and a few fancy touches that set her apart from the crowd. Varnished thwarts give her a touch of class. The boat weighs less than 100 lbs and is small enough for cartop transport. All that, and she still is stalwart enough to comfortably carry 300 lbs of people and gear. Easy to build and fun to sail, she’s a quick-and-dirty boat in swan’s clothing.

This design is a fine choice for the first-time builder. All major pieces can be gotten out of three sheets of marine plywood and one sheet of household grade. Since the boat is built on its own frames, there is no need to build a strongback. While it is possible to build the Salt Bay Skiff with minimal tools, this will greatly slow the process and introduce error along the way. I encourage builders to try and gain access to a full shop, as we did. You’ll find that neighbors with tools like to get involved. Also, many community colleges offer shop access. All this makes life easier and exposes your child to the real workings of boatbuilding.

The Salt Bay Skiff shouldn’t be attempted in a single weekend, especially if you’re building with kids. Ana and I took several weekends to pick away at it. Also, I recommend revisiting earlier editions of this “Getting Started” series, especially the articles on building the Peace Canoe (WB Nos. 195 and 196) as it is a good primer for building the Salt Bay Skiff, with many construction similarities and tips that can be applied. One major difference, however, is that we used epoxy instead of marine-grade polyurethane adhesive. I prefer it because its stiffness is more like that of plywood.

Materials Needed to Build the Salt Bay Skiff

Adhesive

• 2 quarts epoxy resin with hardener

Fastenings

•1 oz 5⁄8″ copper tacks

•1 oz 1″ brass or stainless-steel nails

•100 No.10 3⁄4″ stainless-steel flat-head wood screws

•200 No. 6 1″ stainless-steel flathead wood screws

• 100 No. 6 3⁄4″ stainless-steel flat-head wood screws

• 2 dozen 1 5⁄8″stainless-steel drywall or deck screws

• 1 dozen 2 1⁄4″ stainless-steel drywall or deck screws

• 1 lb No. 8 1 5⁄8″ black drywall screws for temporary clamping. These are the thin ones.

Hardware

• One pair bronze oarlocks and two pairs sockets, with screws

• One pair 7′ spruce oars for rowing, one pair 5′ oars to carry when sailing

• One pair rudder gudgeons with pintles, with screws

• Dinghy gooseneck (buy or make)

• Masthead sheave: 2 @ 1 1⁄16″ x 3⁄8″ and pin (e.g., 2″-long bolt)

• Fender hook, brass snap type (ABI No. 280110)

• High eye strap (ABI No. 151512)

• Small eye strap (ABI No. 151212)

• Four stainless-steel bails for 1 3⁄8″-thick spar

• Four single blocks for 5⁄16″ line

• Five 4″ cleats

• 100′ of 5⁄16″ Dacron line for halyards and sheets

Lumber

The measurements listed below are in “nominal dimensions.” Actual dimensions are slightly smaller than the numbers indicate.

Paint

•1 quart primer

• 1 quart topcoat

Plywood

(Don’t discard scraps)

•1 sheet 4′ x 8′ x 1⁄4″

marine ply: topsides (hull)

• 1 sheet 4′ x 8′ x 3⁄8″

marine ply:bottom, butt straps, frame gussets

• 1 sheet 4′ x 3′ x 1⁄2″

marine ply: rudder, leeboard, transom

• 1 piece 12 1⁄2″ x 45″ scrap 1⁄4″ or thicker ply, particleboard, etc.: temporary aft mold

• 1 piece 1 x 10 (nominal) x 14′ clear pine: chine logs and gunwales

• 1 piece 1 x 10 x 12′ clear pine: keel, frames, transom framing, stem, knees, centerboard tongue, thwart cleats, foot braces*

• 1 piece 2 x 4 x 2′ construction lumber: maststep

• 1 piece 2 x 6 x 1′ construction lumber: breasthook * It’s a good idea to buy a little extra pine in

case of mistakes.

• 1 piece 1 x 8 x 6′ oak: skeg, false stem, tiller

• 1 piece 1 x 8 x 8′ and 1 piece 1 x 8 x 12′ clear Western red cedar: seats and thwarts

• 1 piece 1 x 8 x 10′ clear spruce or pine: mast

• 1 piece 1 x 6 x 10′ clear spruce or pine: yard

• 1 piece 1 x 6 x 8′ clear spruce or pine: boom

The profile view and the plan view show all the parts that make up the Salt Bay Skiff. Each piece is named to help with identification.

Profile View

Plan View

Preparation

Take time to familiarize yourself with the process and make a game plan. Spending some extra time now will spare a lot of grief later. Label every piece as shown before cutting.

Making and Gluing Up Parts

Once the layout, including the frame locations, has been marked out on the plywood and double-checked, use a circular saw to cut out the side pieces, bottom pieces, butt straps, and aft mold. (I drape the electrical cord behind my collar to keep it away from the blade.) Then, cut out all remaining pieces and set them aside for now. Be sure to use the illustrations as a guide, to make best use of materials.

All butt straps are 4″ wide. Set the panel pieces inside-face up on the bench top. Place the side panel pieces edge-to-edge and mark the butt strap outline on the dry panels. Then, wet out all of these areas with epoxy. Also, be sure to wet out the mating face of the butt strap. After all faces are wetted out, add a small amount of colloidal silica to the epoxy mix, and coat all surfaces again. This thickening agent will help to fill any gaps between panel pieces or the butt strap. Place the butt strap on the wetted surface, and fasten with 5⁄8″ copper tacks. Repeat on the other side panel, as well as the bottom pieces. Leave them to set overnight.

Make and install foot braces according to the illustration(previous page). These serve as supports for the aft mold during construction and as foot supports for a rower later on. Here, Dad holds the glued brace while Ana fastens with screws from the outside.

Making Frames

Measure the length needed for each frame section, then add an inch as a precaution and cross-cut to length. I used a chop saw because it is the best and most efficient tool for this operation. Next, it’s time to rip the frame stock to width (above). Ripping refers to sawing along the grain and is most often done to cut long pieces to a specified width. Set the blade at 90 degrees (perpendicular) to the saw’s tabletop. Set the tablesaw fence to a width of 2 1⁄4″, and rip the bottom piece of the ’midship frame. Next, set the blade to a 4-degree angle (off vertical) and rip the bottom piece of the forward frame. Then, with the blade still set at 4 degrees, rip the two side frame pieces for the ’midship frame. Now, set the saw blade angle to 17 degrees (off vertical) and rip the two side frame pieces for the forward frame. The bottom and frame sides of both frames should now have the correct bevels on their respective edges.

Using a bevel gauge, mark the frame angles of the frame heels onto the frame stock. The forward frame is 109 degrees and the ’midship frame is 112 degrees. Then, cut to the marked lines.

Assemble and Install the Frames

Draw a radius or the curve of your choice at the top end of each side frame, making sure each piece is long enough. Lay out the thwart cleat notch and gusset locations. Each gusset should line up flush along the adjacent edges of the frame. This is a good time to check centerline location on the bottom frame piece and all heights and distances in preparation for cutting. When all components are cut, give a light sanding to all inboard-facing surfaces. Also, round inboard corners to prevent injury.

Epoxy all mating frame piece ends and edges to one another. Be sure that all frame pieces are flat on the gluing table, flush with each other, and at the correct angle. Epoxy and nail gussets at their correct locations. Once the gussets are secure on one side, flip the frames and attach the second set to the opposite side.

Thwart cleats give the thwarts (or seats) a solid place to land and attach to the boat. Setting the thwart cleats into side frame notches gives them greater strength. To make the cleats, begin by setting a tablesaw blade to an angle that matches the cleat notches. Once the blade is set up, rip the thwart cleat stock. It’s safest to start with a long, wide board. Ours was about 3′ long and 6″ wide. First, cut one long, thin cleat piece from the wide board, keeping the width of the board between the blade and the fence. Then, cross-cut into smaller pieces of required length. Thwart cleats should be somewhat loose-fitting when set into the frame notches. Finish the job by cutting limber holes (see illustration, previous page) at the bottom corners of both frames.

Stem, False Stem, and Transom

Making the stem and false stem will require you to rip thin and steeply angled pieces of wood on the tablesaw. Begin by setting the blade to rip the 33-degree angle depicted in the drawing on the next page. Use a push-stick while making these cuts. Put scrap from the first cut back in place to steady the piece during the second cut. Repeat this procedure to rip the false stem. Set the false stem aside for now. (Do not yet cut the stem to length! After it is mounted on the boat, you’ll cut it to fit.)

Rip the angled transom frame pieces at the width and angles given on the drawings. After all four frame pieces have been ripped, cut them to length and angle. If this is your first transom frame, consider gathering some extra stock in case of mistakes. Take your time. Pay attention to the orientation of beveled edges.

Once you have achieved good fits with the transom frame pieces, epoxy and fasten them to each other and the plywood transom itself. Let the epoxy set overnight. (Note: We used the full-sized drawings from the plan to build our transom, as well as other parts that have critical measurements and angles. While accurate measurements can be drawn from the information given here, having a set of plans makes these jobs much easier to do.

Pulling it All Together

Begin assembly. Double-check all markings on the aft frame (the larger of the two) and inner face of the hull side pieces. Be sure that the forward and aft faces of the frames are clearly marked so they don’t get turned around during the glue-up. Apply epoxy to the outer edges of the aft frame. Also wet out the mating faces on the hull side pieces. Attach and fasten the hull sides to the aft frame. While Ana drives screws into the frame, I hold a small piece of wood flat across the frame and side piece to ensure that the two remain flush through assembly.

Glue and screw the transom to one side of the hull. Then, attach the stem to the forward end of that same hull side.

Next, tie a soft rope around the hull near the forward and aft ends of the boat. Set up some clamps on the hull sides to keep the ropes from slipping. Then tighten the rope to draw the two sides of the boat together.

Dry-fit the forward frame and the temporary aft mold. Screw, but don’t glue them.

Carefully line up the unattached hull side so that it meets its counterpart at exactly the same height. Epoxy and fasten it to the transom and the stem. Once the second side is attached, permanently install the forward frame.

Chine Logs

Prepare for chine log installation by pre-drilling screw holes along the length of the boat on both sides. Next, rip ten 1 1⁄2″-wide strips of 5⁄16″-thick pine for chine logs and guardrails. Set the guardrail stock (six strips) aside for now.

Roll epoxy on the remaining four strips. The two inboard ones will be coated on both sides.

Coat the mating area on the boat, too.

Bend on a pair of chine log strips and temporarily fasten them with drywall screws as shown.

Use stainless-steel screws to permanently secure the chine log ends. Clamp the ends together as well, along with any other part of the chine log that shows gaps. Leave overnight to cure.

Cut excess chine log length flush with the transom and stem.

Attaching the Bottom

Plane the chine logs flat to prepare them to accept the bottom. Use a straightedge to check your progress. Place the bottom on the boat; check its fit and mark along the outside edge of the chine. Next, climb under the boat and outline the inside edge of the hull. Then remove the bottom and pre-drill a series of holes along the length of the bottom, between the two sets of lines.

Spread epoxy on the chine logs and on the mating area of the bottom.

Screw the bottom to the chine logs using stainless-steel screws.

Install the guardrails, following the same procedure as with the chine log installation. Because the guardrails are made up of three thicknesses, they will require extra clamping to prevent gaps.

The Keel, False Stem, and Skeg

Make the keel by ripping an 11′-long pine board to a 1 1⁄2″ width. Dry-fit it to the boat by clamping it at either end. Outline it, then remove it from the boat. Pre-drill the screw holes in the plywood, according to the drawing. Epoxy the inside face of the keel and its mating surface on the boat’s bottom. Use stainless-steel screws driven from the inside and end clamps to hold it to the boat. Let the epoxy set overnight. In the morning, cut the ends of the keel flush with the boat at the stem and transom.

Attach the false stem. Coat its inside face and its mating surface on the boat with epoxy. Fasten it with stainless-steel screws. Trim the base of the false stem flush with the keel. It’s a good idea to leave the top of the false stem a little long for now. With these bottom pieces complete, it’s time to fit the skeg.

Cut a 1⁄2″-thick piece of oak according to the rough shape called for in the drawing. Lay a flat board along the keel. Next, set the skeg on edge next to the keel. You will see gaps at the ends. Now, take a block and use it to scribe a pencil line along the length of the skeg stock. The line should carry the full length of the skeg. Use a bandsaw to cut out the skeg. Cut carefully and as close to the line as you can.

The Keel, False Stem, and Skeg continued

With the skeg fitted to the boat, draw a line that extends the plane of the transom. A flat board laid along the transom makes a good guide. Cut the end along that line. Then, center the skeg on top of the keel. Outline it in pencil. Mark screw locations about every 6″.

Apply epoxy to the inner edge of the skeg and its counterpart area on the keel. Fasten the forward end from the outside with stainless-steel screws. Then, from the inside, drill, counterbore, and screw some long screws into the deepest parts of the skeg.

Chris Franklin has worked in boatyards from California to Paris and has been designing boats in Maine, primarily with Bruce King, since 1990. He and daughter Ana wish to thank the Carpenter’s Boatshop in Pemaquid, Maine, for hosting this project.

Although you can build the Salt Bay Skiff directly from these pages, working to large-scale plans with full-sized patterns will ease the job. These plans ($50, shipping included) are available through the designer, Chris Franklin. He owns Bruce King Design Associates, LLC, P.O. Box 599, Newcastle, ME 04553; <www.brucekingdesign.com>.

In our next installment, we’ll fit out and finish the hull, rig the boat, and go sailing.