A Beginner’s Guide on What to Do — and Not Do — Aboard a Boat

The best sailors learned their skills by watching more experienced sailors, but your first few experiences aboard a boat will likely be somewhat bewildering. Five feet from the dock is a whole new world; let this guide introduce you to that world.

Any new crew member has two primary tasks. First, keep yourself safe and comfortable so you can pay attention to this new world. Second, be a polite, cooperative guest so the skipper will welcome you back.

There’s a sensible saying at sea: “One hand for yourself and one hand for the ship.” It means that your first job is to take care of yourself, so you can take care of the boat. Be aware, hold on, be stable. Brace your back and feet against something solid when you sit. Whenever you move, look for the next reliable handhold, so you’re balanced, even when the boat is rocking. Try to get the rhythm of the boat’s motion, and move with it. It’s like dancing.

Being a good crew member is mostly about paying attention and being open to learning as you go along. Stick with the essentials: stay safe, adapt gently to the new environment, ask thoughtful questions, listen to the skipper, and don’t get in the way. If you can do that much, you’ll be comfortable aboard before you know it.

Before You Set Out

Time

If the skipper plans to leave the dock at 0940 (that’s 9:40 a.m. on the 24-hour clock, the common way of telling time aboard), he might be planning to catch the tide changing at that hour. For the landsman, the tide goes up and down. For the sailor, it’s also powerful current moving in and out, helping or hindering his boat. Sailors pay close attention to the tides. Be on time.

Be flexible, too. The skipper can’t predict the winds and weather. He may estimate a return by 1530 (3:30 p.m.), but don’t schedule an important meeting at 1600 (4:00 p.m.), because the boat may not get back until much later. Boats are at the mercy of big forces that change without warning.

Clothing

On the water “wearing is layering.” Even on a warm day the sea wind can be cold. Conversely, on a cool day you can work up a sweat. Wear layers you can peel off or put on. A fleece sweater and a windbreaking rain jacket are always good to have when headed out on the water.

A hat is also a smart idea. On cool days, you lose major amounts of heat from your head; on sunny days, the hat bill will keep the bright sun out of your eyes so you can see more clearly, with less squinting.

Hats blow off. You can buy a “hat keeper” with two clips, or sew a cord from side to side for the same purpose.

PFDs

“Personal Flotation Devices” are life jackets. The U. S. Coast Guard requires every boat to have a PFD on board for each crew member. Should you wear one? Ask the skipper. Some sailing clubs make wearing PFDs a rule. Your skipper may have his own rules; if he wears a PFD, you should. If you don’t swim, you should positively wear a PFD, and if wearing flotation makes you feel less apprehensive, put one on. But wearing floatation gear isn’t about your swimming skills. A PFD is designed to keep even an unconscious person floating upright. If, heaven forbid, you do go overboard, the PFD allows you to remain upright until you’re picked up.

Shoes

Boat decks are almost always wet and slippery. Boat shoes with special slit-rubber soles are best. In any case, wear shoes with rubber soles that won’t leave marks on the deck. Sandals with proper soles are common and comfortable aboard boats, but they should not be of the “flip-flop” variety; they should have captured heels, so you don’t slide out of them. Open toes can make you trip over lines. In fine weather your bare feet will often do nicely, though they’re more slippery than you think and are vulnerable to toe-stubbing on deck hardware.

Sun Protection

You get much more sun in boats because you receive sunlight reflected from the water’s surface all around you in addition to that which you receive from above. A hat will help, but high-SPF (sun protection factor, usually above SPF 30) sunblock is a necessity. Sunglasses, especially ones with polarized lenses, are a comfort on any but the cloudiest days because the sea reflects and maximizes the light.

Hydration

Bring plenty of water or sport electrolyte replacement drinks, even when it isn’t hot. The sun and the wind dehydrate you.

Keep it Together

Carry your things in a sturdy bag that is easy to stow. One superstition is that bringing a suitcase aboard is bad luck. Here are a few other things that are best left ashore:

- Don’t bring delicate breakables, as boats are unstable environments that rock and roll.

- Don’t bring anything that could be ruined by a shower or spray, which is a fact of life on board.

- Don’t bring noisy things like CD players or radios; sailors develop a respect for quiet. Loud music could drown out important sailing orders, and noise has a way of distracting attention.

Once Aboard

Boat Culture

Customs that may seem odd or out-of-date have good reasons for their existence.

Before stepping on deck, ask, “May I have permission to come aboard?” This question is like knocking on the door. It’s an old naval tradition and a sensible thing to do. You’re asking the captain if the boat is ready for you, where to step, where to sit, and where to put your things. You’re also being respectful of the skipper’s control over his space.

Addressing the boat’s commander as “Captain” or “Skipper” shows your respect for the authority and responsibility any boat-handler carries. Even in a dinghy, you may address the person who is directing the boat as “Skipper” or “Captain.” The captain will tell you if he or she prefers an informal address. But in the beginning, you can’t go wrong using the honorific title.

Asking not only displays good manners, it’s a good safety drill. Ask before you go forward; the skipper may be planning to tack (turn) or trim (adjust) the sail. Ask before you go below, so the skipper will know where you are at all times. Ask before you tie or untie a line, throw an electrical switch, or pull a lever. Natural forces like wind and waves are unexpectedly powerful, and you don’t want to unleash them haphazardly. Always ask—there’s no shame in it.

Stowing Your Gear

Putting your things out of the way is important on a boat because the walkways on deck and below should be kept clear. Lumping them on a berth (seat) or countertop isn’t a good solution; everything shifts when the boat heels (tips). Ask about a good place to stow your gear, and get some help the first time.

Stay in the Boat

Don’t hang over the rail, trail your feet in the water, “ride the bow,” or jump about. Generally, stay in the cockpit and don’t cause your shipmates to worry about your safety.

When you’re in a small boat, like a dinghy, approaching the dock or another boat, it’s essential that you keep your fingers inside the boat! Don’t grab the rubrail for support (see the illustration up top). The force of a wave lifting a small boat against a dock, the hull of a large boat, or even another small boat, is enormous. Fingers are delicate and indispensable.

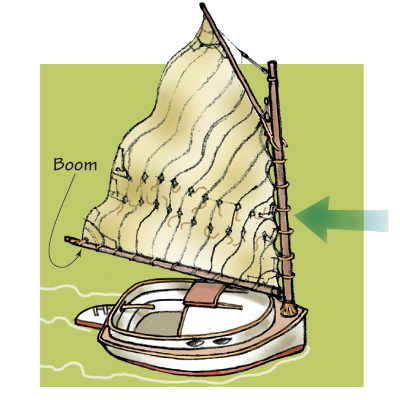

Boom!

The most dangerous item on a sailboat usually is the boom, the spar at the foot of the sail. In some common situations there is a real possibility of the boom whipping from one side of the boat to the other with great force. Consider the boom a “widow maker” and stay low so it can swing overhead and clear of you.

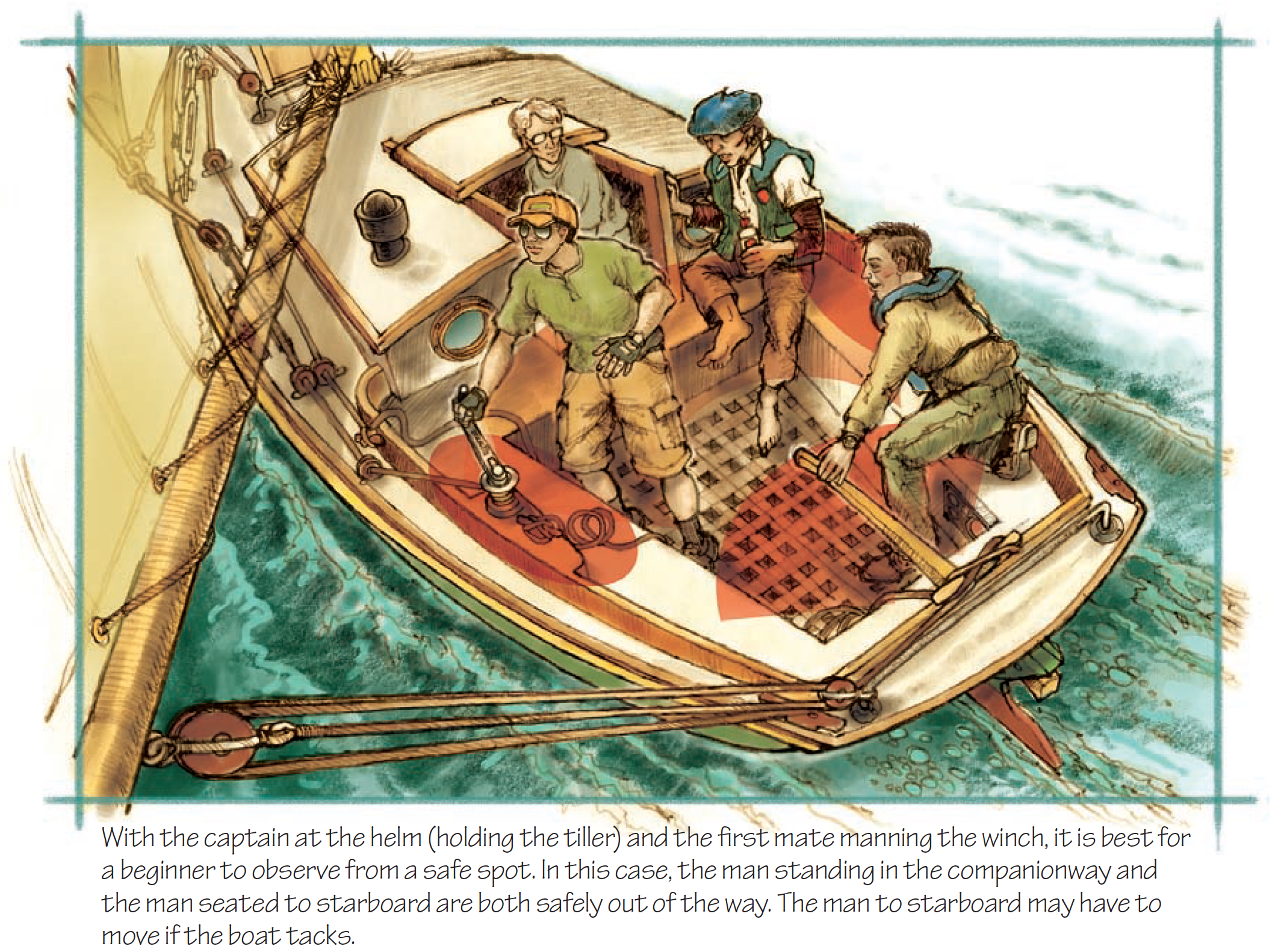

Traffic Pattern

You’ll see an obvious traffic pattern as the boat’s crew works. It’s usually a triangle (skipper at the helm, first mate crossing sides to handle the jib sheets), but every boat is a bit different. On your early voyages, your job is to keep out of that pattern so the crew can work smoothly. You may be asked to help with the work; if you are, keep the pattern in mind and don’t block it.

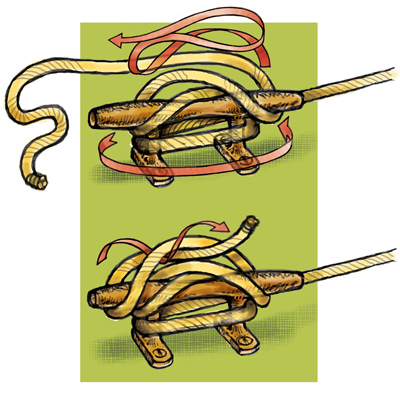

Line Beware

“Rope” isn’t a word sailors use often. The word refers to the raw material on a spool, but once a piece is cut from that spool, it’s called a line. What a line is subsequently called depends on what it does:

- Sheets control the angle and shape of sails

- Halyards lift and lower sails, spars or flags

- Rode refers to the anchor line

There are also nettles, dock (or “mooring”) lines, guys, lifts, and a dozen other specific ways cordage is named. But all lines present potential hazards. Sailors talk of “the malevolent intelligence of line,” meaning its tendency to grab a foot or a hand or even a neck at the wrong time.

Stay clear. Don’t get tangled in coils. On a boat, slack lines can suddenly tighten without warning. Winches and cleats holding line under tension are potentially dangerous. Watch your fingers and thumbs. Safe procedure becomes second nature as you learn the ropes, but be especially cautious at first.

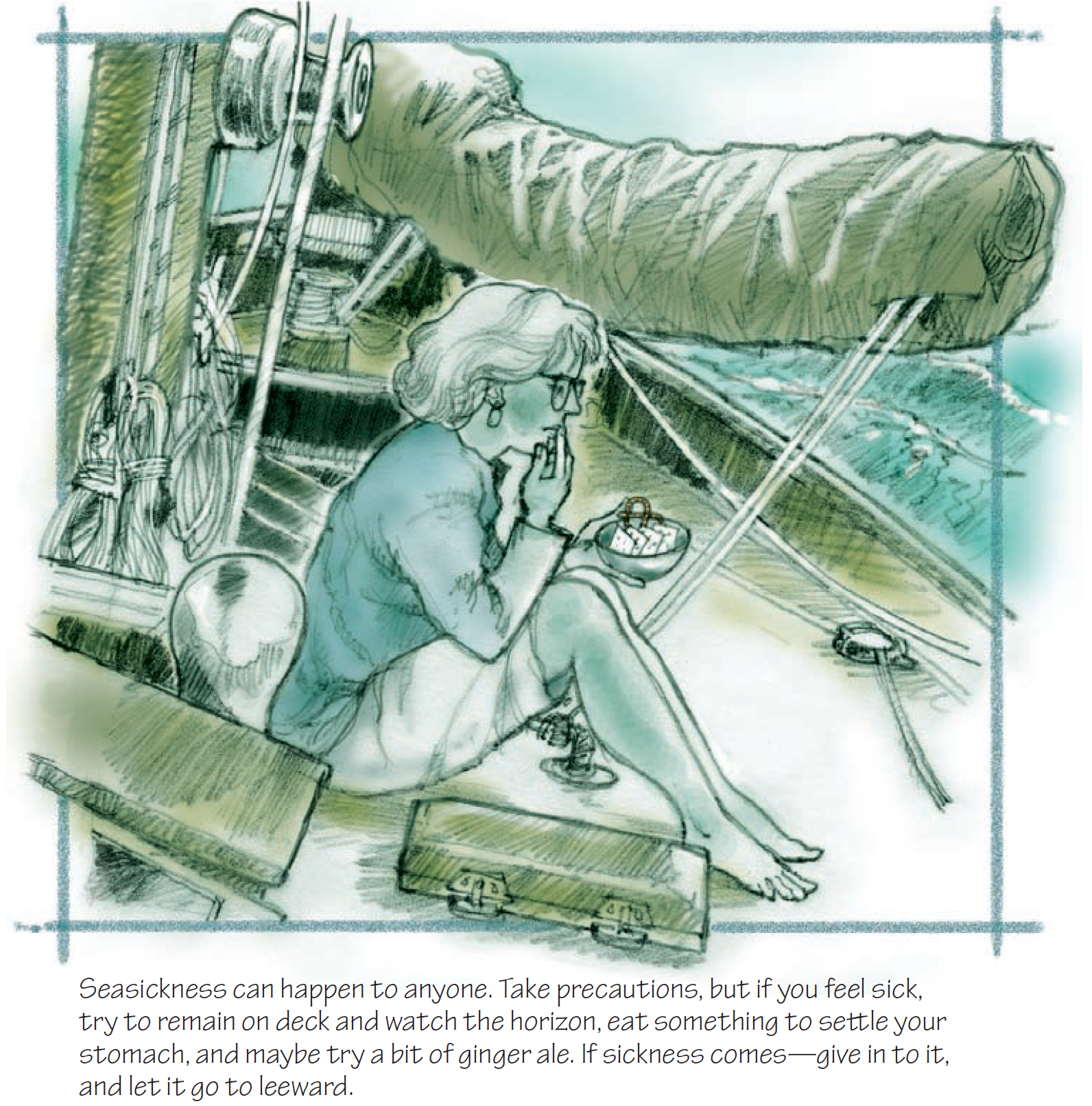

Seasickness

A boat slides, heaves, and rocks on its liquid medium, tossed by variable winds and waves. This might seem scary at first. Basically, though, sailboats are at work when they tip. They’re built to heel (to lean over with the forces of the wind in the sails). It may look dangerous, but it’s normal. Watch your shipmates. If they’re not worried, there’s no reason for you to fear. Fear can contribute to seasickness.

Seasickness is no fun. Don’t let anyone tell you that it’s “all in your mind,” either. It’s a serious condition caused by a disconnect between what your eyes report and what the motion sensor of your inner ear records. Everyone gets seasick occasionally, even admirals (Admiral Lord Nelson always got seasick at the beginning of a voyage, and he didn’t do badly as a sailor).

To minimize your chances of getting seasick, get a good night’s sleep and eat a moderate, easily digested breakfast before your voyage. Keep in mind that the disconnect between visual recognition and inner-ear balance can be made worse by fear: if you’re nervous about being on the water and about getting seasick, you’re more vulnerable. Approach your voyage with confidence. Trust your captain and the boat. Take it easy; ask questions to soothe your fears. Expect to have a good time.

Motion sickness medications are proven aids and will almost certainly keep you well, though they may make you drowsy. They’re most helpful if you take them an hour before you reach the boat. Over-the-counter Dramamine and Bonine are excellent. Your doctor can give you a prescription for even stronger drugs like scopolamine.

On your first voyages, don’t tax the connection between eyes and inner ear by reading or by putting your head down on the boat to watch the waves. Stay upright and watch the shore and the horizon. This lets your eyes and your inner ear compare notes. Stay on deck, and avoid engine exhaust. Ask for something to do, like steering or coiling line or looking out for buoys. Stay away from alcohol, too.

Okay, so you’re sick. Go ahead—throw up. Throw up to leeward, the side away from the wind. Get it over with, with no false pride. You can comfort yourself with cola or ginger ale. Nibbling pretzels, saltines, or ginger cookies may also help. Some people feel better after a little nap.

Calls of Nature

A boat’s toilet is called a “head” (long ago, the “seats of ease” were a row of holes on a bench, way up forward on a ship, at its head. The name has stuck). A boat’s head is not as easy to use as the toilet in your house. Ask a shipmate to advise you on its operation before you try it out.

Sailors can be overly concerned about holes in a hull, but a few holes are absolutely necessary—like the engine water intake and outflow, the sink drain, and the inflow and discharge for the head. Each hole usually has a corresponding valve called a seacock that can regulate flow and seal off the hole as needed.

For the head to operate, one of these valves (called the intake) must be open to allow water to flow into the bowl and another (called the discharge) must be open to allow waste to flush out through a hose to the open sea or to a holding tank. Ask for help in finding and opening these valves. Also ask if the skipper wishes to keep them closed when the head isn’t in use. (They should always be closed when the crew disembarks.)

Remember that once you make your deposit, you may add only a moderate amount of toilet paper. Don’t put anything else in the bowl. All marine heads are fussy about what they will process. Something as small as a matchstick can jam the works, and a malfunctioning head is an unpleasant problem.

Privacy, modesty, and squeamishness diminish with distance from shore. Sailors of both sexes are more casual and direct about natural functions because the boat is small and they are, after all, shipmates. If you’re shy about this initially, you’ll likely get over it.