The stem

I’d like to read from my Ode to the Black Locust, but fortunately it’s still all in the head, and hazy at that. The subject is the Stem. Out front every time; first to take the brunt, whatever that is; symbol of Man’s conquest of the unknown; stark in the cresting seas, the boiling sun, the creaking frosts of high latitudes. And not always up to facing these responsibilities, either, unless it’s a pretty good piece to start with, and capped at the top to keep fresh water out of the end grain.

So, for the stem, you want the best cut out of the best tree that ever grew. This is where the old pro has the advantage over you. For years, he’s been pushing choice bits of timber under the shop-crooked, curved, too rough-looking to suit the visiting N.A.s-waiting for that slack spell when he’ll build one for himself, or for a friend who’s going winter fishing. He might even have a piece of black locust, grown to the sweep, clear of the heart, and seasoned all the way through. A piece of really good, genuine white oak, grown and seasoned as above, is not to be sneered at. Dense hard pine would do, but you’d likely have to accept straight grain. Just don’t give up the search too easily. And if all else fails, you can cold laminate the whole length, on a form, with no scarf, out of ¼-inch hard mahogany-and with plenty of through-rivets to quiet my doubts about the glue. We’ll consider this possibility later.

Let’s assume that you plan to make the stem in two pieces, as shown in the present plans. It’s permissible to shift the location of the scarf up or down, to suit your timber. Don’t shorten the scarf, or I’ll be disappointed. Don’t put jogs, hooks, or keys in it. Keep the lower end of the scarf below the waterline. Make the whole assembly of three pieces, as shown in Figure 5-la, if necessary. Leave plenty of wood on top of the keel, far aft enough to take that forwardmost ballast bolt with plenty to spare. You can cut all these parts, even some portions of the inside curves, just as you cut the keel and the sternpost; although with these lighter-weight and easier-to-carry timbers, a big handsaw does it with less fuss. Dress off the matching faces of the scarfs with great care, square to the sides and right to the template outlines, light-tight when you put them together. Use a rabbet plane across the grain in the corners, and a smoothing plane and a foreplane in the open stretches. Transfer waterlines, sheerline, and station lines to all four faces of each piece they cross; prick in the rabbet line (but do not mark it yet) on both sides, as you did on the stern post. Lay them out on the full-sized lofting, and notice what happens to the height of the sheer when you change the angle of that scarf at the fore end of the keel.

Figure 5-1a

Joining it all together

My first move, at this point, is to set the wood keel level, on timbers, and fit the forefoot (lower part of the stem) to it. Use a tackle from overhead, unless you have a strong and patient helper to hold it while you scramble for clamps. You were probably timid in cutting the end of the keel and the matching jog in the forefoot, so you’ll probably need to make saw cuts up the joint-several of them-before the reference lines (marked on each piece at station 3) match up. Set your clamps so that they tend to pull the two pieces together lengthwise, tightening the scarf as you tighten them. As shown in Figure 5- la, check with a long straightedge against each side of the forefoot to points 2 inches off center, back on the keel top.

Now, if you have absolute confidence in your clamps, you can lay the assembly on its side, counter-bore for heads, and bore up through them from the bottom of the keel. The two forwardmost counterbores must be nicely calculated for depth, to allow for final fairing and shaping of the keel. For strength, the ideal is to set the heads barely below the surface (not enough to hold an honest bung) in order not to remove too much wood by counterboring. You can thicken epoxy resin with sander dust and get a paste that will stick to anything, anywhere including the sunken bolt heads. Note the angle of the bolt holes, as shown in Figure 5-1 b. They are laid out to range forward of a line perpendicular to the top of the forefoot, so that they will tend to pull the stem aft, against the end of the forefoot, as the nuts on top are tightened. Bore half of them square to the joint, if you want to, but never on a line that will bring them out at right angles to the top of the forefoot.

Figure 5-1b

Start them all dead center at the bottom, but angle all but the end bolts alternately port and starboard-enough to come out at the top 1 inch off center. Square off a flat, with gouge and chisel, to take a washer and a nut, where each bolt hole breaks through at the top. ,Notice the bolts through two floor timbers, to be put in later. Lay out the fastenings with care, to avoid interference with these floors. For material, use silicon bronze, 1/2-inch diameter, for these wood-to-wood scarf bolts-and 7/sinch galvanized steel, of course, for the aftermost bolt, which passes through the iron ballast casting. Remember that a giant ( the outside ballast keel) will plant one foot on this scarf and try to tear the planks and the stem away from it, with a strength that might produce 9,000 pounds of pull, so it’s wise to keep this earnestly in mind when you’re putting these parts together.

Figure 5-2a

Very well, then. Stand it up, unclamp, soak the contact surfaces with your favorite poison, reassemble, drive the bolts, and set them up with nuts and washers. Counterbores should be 1 inch deep, and bolt heads can be made by threading on a standard full-depth hex nut of the same bronze as the bolt.

Figure 5-2b

Hoist the top piece of the stem, and sag it into place on the forefoot with two clamps to hold it there. Run your saw blade through the butt joint at the top and bottom of the scarf, and let it slip down (with, maybe, someone on a stepladder gently tunking it at the top) to make an airtight fit. The load waterline marks should run together as reference marks when fitting is complete. Lay out the lines of the bolts; counter bore for same (½-inch bronze); bore end holes to center, and the two in between aimed to port and to starboard, and slant them all as before to pull the two pieces together when the bolts come tight.

Figure 5-2c

Sternpost next. This is a tricky bit of business, because you must fasten it first to its knee, then-knee and all-to the wood keel, while leaving room for the bolts from the ballast, and for the fastenings from the outer sternpost. Take a good look at Figure 5-2. Bolts 1 and 2 hold the knee to the post; bolt 4 and drift 3 hoid the assembly to the keel. Bolts l and 2 are ½inch bronze; bolts 3 and 4 are galvanized steel, ½-inch and 5/s-inch diameter, respectively. Locate and mark the after end of the rabbet line on the keel from the profile drawing, and bring the rabbet line already drawn on the sternpost to that mark (Figure 5-2b). Check that things are in correct fore-and-aft alignment by using a straightedge to the side, just as you did with the forefoot. Clamp as best you can, and have your helper support it tenderly as you lay the whole assembly on its side once more. Pray, and bore. Bolt and drift.

Figure 5-3

How good are drifts?

Drift, did I say? The word is out at last, and open to suspicion and attack. Drifts will be coming up (or if you care to be precisely literal, going down) very frequently from now on; so I’ll say grace over the pork barrel right now, and sanctify all our meals for the next six months. We’ve had drift trouble. Once we tried boring for them a sixteenth scant, according to the book-in hard, dry oak, mind you-and had them fold like spaghetti before they were halfway home. We cured this by using a slightly worn ½-inch auger for a fat ½-inch galvanized rod-and reamed the floor timber with a new barefoot auger, so that there’d be a fighting chance of driving the drift all the way. The head swelled nicely to fill the clinch ring, no fear.

The big trouble comes from the owner. “For goodness’ sake,” says he (or words to that effect), “you don’t really think those things will hold, do you?” So we start one for him (with no grease on it), hand him a hammer (not the best-balanced one we own), and invite him to drive. That’s all it takes. Half an hour later, he has been converted to drifts; we saw off the battered remains, and tell him these things really get set after they’ve been in the wood a few months. Drifts are good fastenings. But don’t use cast-iron clinch rings; they’re brittle and they’ll burst at the last blow, every time. Flat steel washers can take it, so use them instead.

Cutting the rabbet

Here we are now, with keel, stem, and stern post assembly fastened together and lying on its side, waist high, with room around it. This is the backbone of your boat, and now, before you set it up in final position for building the boat, is the time to cut the plank rabbet and frame sockets. This operation terrifies some amateurs; and I’ve even known pros who dared not do it before the molds were up. Be not afraid; it’s simple. Be not timid about it, either, comforted by the thought that you can always increase the angle and finish to full depth as you go along. The frame sockets derive their precise depth and angle from the rabbet cut, and you’ll compound a windy night with a rainy morrow if you lack bold confidence. So get a clean little board-say, 4 inches wide, 18 inches long, straight on both edges-and a bevel gauge, a pencil, a steel tape, and the lines drawing of this boat. We’ll try to lay and cut this rabbet.

Draw a straight line down the middle of the board, parallel to the edges, as shown in Figure 5-3. This represents a horizontal line along the flat side of the stem or the stern post (any load or water line), or it represents just as well the vertical side of the keel at any station mark. And I mean vertical, allowing for the drag of the keel, and not simply square with its top. Go now to the body plan in your lofting on the floor, and set your bevel gauge to the angle made by the intersection of the outside of the planking and the side of the keel at the rabbet mark for station number 3. Transfer this angle to your board-edge of board to centerline and mark the point of intersection “R” (for rabbet line-representing, on your board, the outside of the planking).

Figure 5-4

Square in from this angled line, at “R”, the thickness of the planking you intend to use (in this case, 15/16 inch). This new point, labeled “M” (for middle line), represents the inside corner of the rabbet cut, and is a cinch to locate in this view (body plan), but not so apparent when you look at the side of the keel, as in the profile. But we’ll dig to it, unerringly. Draw a line from this point, parallel to the “outside of the planking” line exactly 15/16 inch from it, of course-and note the point of intersection with the centerline (side of keel), which you label “B” (for bearding line). The distance from “B” to “R” is what you get from all this, and nothing more. Measure it. I get 21/16 inches. Measure up from the rabbet line-along the vertical station line, on the side of the keel-exactly this distance, and make a mark. Now go through this whole process for all the other stations along the keel. You’ll find that “B” is somewhere above the top of the keel, at station number 6 and beyond. Clamp or nail a square block flush with the edge of the keel at station number 6, and mark the correct height for “B” on it (see Figure 5-4).

So far, so good. A fair line through these points (marked with a batten, of course) will give you the bearding line (see Figure 5-4.) Don’t mark it yet. Finish up the stem, by using waterlines instead of body plan section lines. You are now working in a horizontal plane, but the method is exactly the same. Take the angle at the sheer from the full-size halfbreadth you laid out on the floor long ago. Get the angles at the load waterline, 12-inch and 24-inch waterlines, from the half-breadth plan in the scale drawing of the lines (Figure 5-5 ). You’ll be told that this is impossible, but pay no heed-angles stay the same, even though the scale of the drawing changes. Develop the distances from “R” to “B” on your board, just as you did it for the vertical stations, and lay these distances off along the horizontal lines-never at right angles to the rabbet line.

You’ll get a nice check for accuracy at the load waterline, because you already have a mark on station number I, only inches away. Go back to the stern post, and do what you can from the waterlines provided. Here’s the place to be timid. Save most of the marking and cutting here until you have the molds set up, battens to go by, and adze in hand. This is not merely the safest way, but also the easiest.

Out with your battens, then, and mark the bearding line. It should be a fair, logical curve, with no abrupt changes. Cut yourself a gauge stick-exactly the thickness of the planking, about 2 inches wide, 1 foot long, and square at both ends. Sharpen your ½-inch and I ½-inch chisels.

Now lock your bevel gauge to that first angle you took at station number 3, and stand the gauge alongside the station mark, so that its blade represents the garboard plank (Figure 5-6). Start a chisel cut just clear of the rabbet line, and precisely at right angles to that line of the bevel blade. Start another cut near the bearding line, and try to visualize the point “M” waiting for you down there in the heart of the oak, The cut from the bearding line to “M” will, of course, be parallel to the line of the bevel blade.

Figure 5-5

Figure 5-6

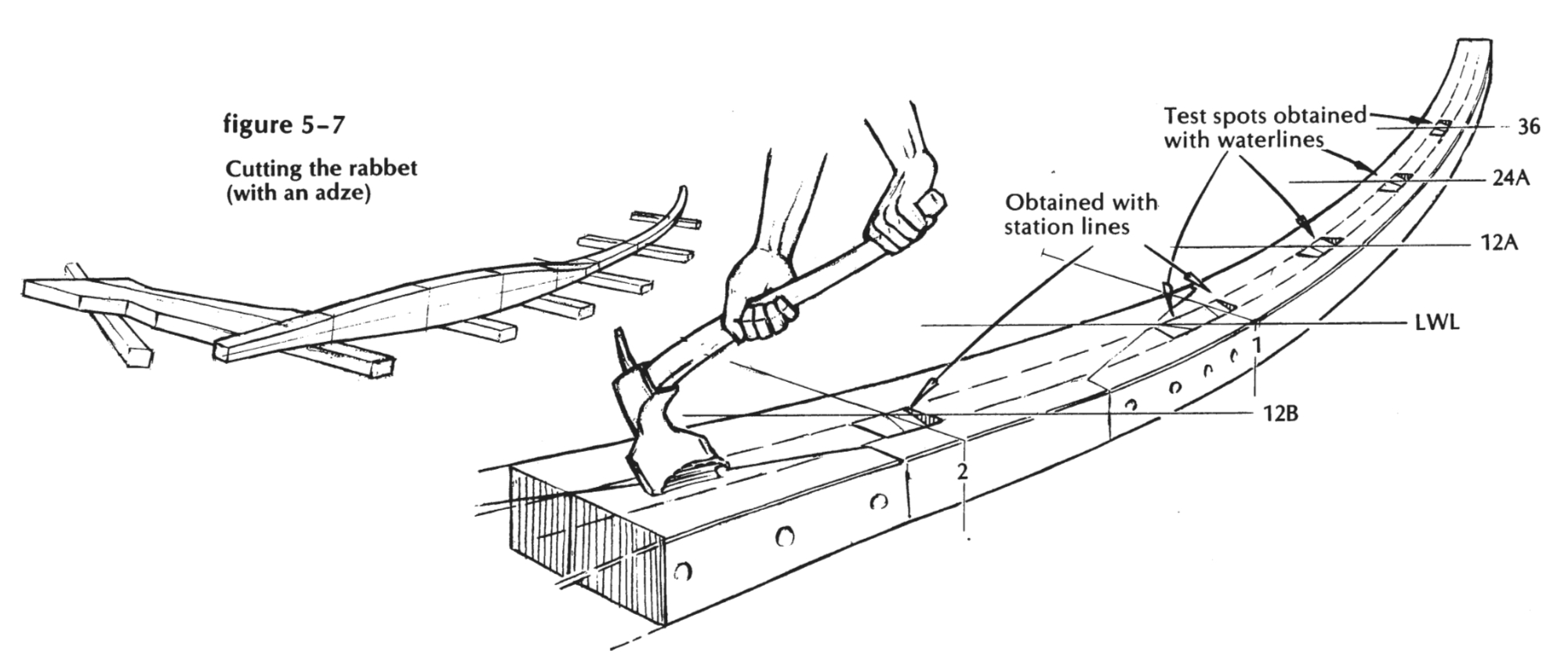

Make the cut wide enough, fore and aft, to take your gauge stick-and keep cutting, with many trials for depth, until the stick is flush at the rabbet, resting firmly at the bearding line, and butting square against the face where the lower edge of the garboard will bear. You have found “M”. You’ll be quicker on the next spot, and the next-until you have proved the rabbet at every station, and at every checkpoint on the stem (Figure 5-7). Now finish cutting the rabbet between spots. I usually rough out most of the wood with a big chisel, and finish with a rabbet plane. Friends will urge using a power saw and a router to speed it up, but I’d stick to hand tools, myself. Those bevels change very subtly, and take some watching and feeling out.

Figure 5-7

Shall we cut the boxes for the frames? This is something more than a formal invitation to the dance. No one is going to change my mind on this question, but you may waver to arguments from the opposition. The Herreshoff boats, the Concordia yawls, and Bill Simms’s ocean racers are all built with frames fastened to floor timbers only. This is a mighty triumvirate to go against. There are those who will tell you this boxing-in of frame heels is a sheer waste of time, an open invitation to dry rot, a poor subterfuge to hide the lack of properly fitted (and properly numerous) floor timbers.

With this I disagree, maintaining steadfastly that direct fastening of the frames to the keel is a fine thing, adding tremendously to the strength of the boat, and fully justifying all the time it takes. So make up your mind; but as long as you’re with me, you may as well learn to mark and cut frame sockets. There’s a trick to it.

Run to your table saw and cut out two or three frame heel facsimiles (gauges 1 and 2 shown in Figure 5-8). For this boat, they will be 15/s by 1 ¼ inches, with sides exactly square to faces, and about 1 foot long. Make them of hardwood, because they’ll be treated roughly. Saw their ends square. Set your locking bevel to the rake of the station marks down the sides of the keel. Mark, on the flat side of the keel above the bearding line, the exact center of each frame-one 6 inches to each side of the station mark, and another 18 inches to each side.

Figure 5-8

Be sure to take these distances not along the sloping run of the keel, but rather, parallel to the waterline-square to the station marks on the sides. Be precise about this. You’ll mark the other side by the same system, and you want to wind up with matched pairs. Mark one forward of station number 1, and one aft of station number 6. There’ll be no more boxes forward of station number 1, and those aft of station number 6 can wait until you’ve finished the rabbet there, with the keel up.

Start with a frame between stations number 4 and 5. Mark a plumb line, with a pencil and pre-set bevel, on the flat above the bearding line, half the frame width aft of the center mark-in this case, 7/s inch. Now lay one of your marking pieces against the back rabbet, as if it were the rabbet gauge, and with its after edge precisely in the same plane-square athwartships-as the vertical line marked on the keel. Mark each side where it bears against the back of the rabbet. Hold it still, and slide its twin down the inner face to contact with the keel.

Mark the line of contact, which gives the necessary depth of the cut at that point. Slide the first piece up 1/2 inch clear of the middle line, and mark across its bottom edge. This is all very simple so far. Mark for the forward edge of the cut-up on the flat side of the keel-and proceed to remove most of the wood inside the marked socket outline with a 7/s-inch auger, boring exactly square to the surface of the back of the rabbet (which is how the frame will naturally lie). Count the turns, and you’ll soon learn just how many will give you the proper depth-which will be 1 ½ inches, leaving 1/s inch for cleaning up with the chisel. Square the socket, also with a chisel, to a good drive fit for your marking piece.

Now move to the mark on the stem forward of station number 2. Mark your vertical line, 7/s inch aft of the frame center, on the flat above the bearding line. Hold the marker against the back rabbet, as before, with the after edge in an imaginary athwartships plane that passes through that vertical line. Use a square from the side of the stem, at the line, to touch the edge of the marker at the top. Now sight along the side of your marker, and notice (and mark) the direction the cut must take, in order that the frame may stand plumb when in its socket.

This line leans away aft at the top, and bears no exact relationship whatsoever to the vertical line. You must project the planes of the sides of your marking gauge onto the flat, and cut out to those marks. They may look crazy, but they are right. Slide the second marker down the inner face of the first one, as before, parallel to the rabbet, and touching the flat of the stem with its inner, lower edge. Mark that line.

Mark around the bottom and sides of your marker on the back rabbet, with its corner at the bearding line. Believe those marks, even if they happen to look all wrong. Bore square to the back rabbet, clean out the socket with a chisel, and try the marker for a fit. I trust that it fits well and stands true, and that you now know how to mark frame sockets. Every one will be a separate problem; every one must be projected from the flat sides of your marker. Once you get the routine established, you’ll mark one in two minutes, and cut it in ten. Six to the hour-but don’t hurry the first few.

Turn it over and finish the backbone’s other side, and we’ll set her up in the next chapter.