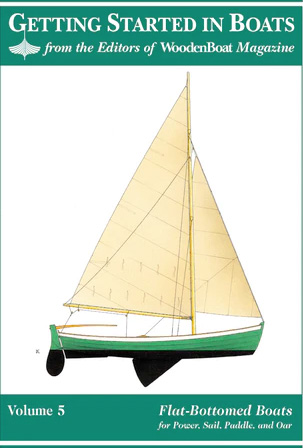

CATBIRD 16

This Chesapeake camp-cruiser will carry us across the Bay and (with 6″-board-up draft) take us up the farthest creeks of the Eastern Shore. Catbird’s cat-ketch rig offers easy handling, and it looks fine. Her sprit booms, combined with jib-headed sails, will prove a revelation to the uninitiated. This arrangement goes by the unwieldy appellation “leg-o’-mutton” on the Bay.

Let’s take a look at its advantages. The foot of each sail (in tension), working with the sprit boom (in compression) and the mast, forms a triangular boom-vang that allows us to control sail shape and twist. To flatten the sail and lessen twist, take up on the snotter (the line that secures the boom to the mast) and/or slide it farther up the mast. Reverse the procedure to put plenty of shape into the sail for light-air work.

We can accomplish this magic with almost no store-bought hardware. At the mastheads, the halyards pass through well-faired drilled holes—“dumb sheaves” or “bee holes,” we used to call them. No blocks, expensive or otherwise, are required. Because the sheets need only pull the booms in, not down, they can be lighter and simpler.

We can build Catbird with the open cuddy as shown, or we might eliminate the cabin to create a deep cockpit that measures a full 13′ in length. Perfect for daysailing a party or camp-cruising a couple…. Although elegant in shape, this hull will go together easily. For the most part, it consists of straightforward sheet-plywood construction.

Fitted with a pair of rugged oars for rowing poling, and fending off, this good little boat will take her crew just about anywhere they ought to go.

Plans from Chesapeake Marine Design, 794 Creek View Rd., Severna Park, MD 21146; 800–376–3152; <cmdboats.com>.

In our previous issues, Maynard Bray described the traditional construction of his Lumberyard Skiff, and John Harris showed how to build his sheet-plywood Peace Canoe. With the lessons learned from those projects, you can build a fleet of simple and handsome craft.

Here’s a gallery of good flat-bottomed boats: a fast and stable kayak, a daysailer, a rowing/sailing skiff, a camp-cruiser, and two rugged outboard boats.

—Eds

Catbird 16 Particulars

LOA 16’0″

Beam 5’4″

Draft (cb up) 6″ (cb down) 2’6″

Weight 350 lbs

Sail area 110 sq ft

In our previous issues, Maynard Bray described the traditional construction of his Lumberyard Skiff, and John Harris showed how to build his sheet-plywood Peace Canoe. With the lessons learned from those projects, you can build a fleet of simple and handsome craft.

Here’s a gallery of good flat-bottomed boats: a fast and stable kayak, a daysailer, a rowing/sailing skiff, a camp-cruiser, and two rugged outboard boats.

—Eds.

The easily built and shoal-draft Catbird 16 will take us daysailing and camp-cruising just about anywhere we ought to go.

WILLY WINSHIP

Willy Winship Particulars

LOA 13’9″

Beam 4’10”

Draft (cb up) 5″ (cb down) 2’3″

Weight (rigged) 200-250 lbs

Sail area 92 sq ft

John Atkin, frustrated by the complex “skimming dishes” that pass for sailing trainers at many yacht clubs, designed the robust Willy Winship to teach seamanship as well as racing technique.

John told us that he derived Willy’s hull lines from the working skiffs of the New Jersey shore. In their earliest form, those boats were planked up with lapped cedar strakes. Their bottoms, cross-planked with the same wood, were narrow and strongly rockered (curved upward forward and aft). The old skiffs were meant to be rowed, and they could move surprisingly fast in calm water.

Dacron, not spruce or ash, would supply Willy’s main source of power. So John gave the little boat relatively more overall breadth and a slightly flatter run than its forebears. He kept the characteristically narrow bottom of the rowing skiffs. The high, flaring topsides provide buoyancy, and they are striking to look at.

The designer, who held no particular liking for plywood, specified that we build this skiff with lapped 9⁄16″ cedar planks for the sides. Its bottom would be cross-planked with the same pleasant softwood to measure 3⁄4″ thick. A small sheet of drawings, perhaps a nod to changing times, describes plywood construction for the hull (3⁄8″ sides, 1⁄2″ bottom). We might be inclined to combine both versions: a plywood bottom to keep the shallow bilges dry even if Willy lives on trailer, and lapstrake cedar sides for their appearance and the good fun of hanging the planks.

Unless we plan to chase silver at the local yacht club, let’s think about sticking a simpler rig into our skiff. The Chesapeake-style leg-o’-mutton (page 2) or a lug rig would work well, and neither requires store-bought hardware.

If we take care with the construction, Willy Winship will be thought a good-looking boat along any waterfront.

The sloop Willy Winship serves as a casual daysailer or competitive yacht-club racer.

Plans from The WoodenBoat Store, P.O. Box 78, Brooklin, ME 04616; 800–273–7447, <www.woodenboatstore.com>. You can write to Atkin Boat Plans at P.O. Box 3005, Noroton, CT 06820

San Juan Dory 16

San Juan Dory Particulars

LOA 16’0″

DWL 13’6″

Beam 5’7″

Draft 6″

Weight (empty) 300 lbs

Displacement 825 lbs

Power 10–20 hp

Designed and built by David Roberts, the San Juan Dory seems typical of plywood dory-skiffs that developed during the 1950s. Similar boats work the lagoons and flat beaches along much of our coast. They rake clams, net crabs, catch fish, and carry just about anything that needs to be moved from here to wherever; and the best of them (such as the San Juan) look just fine as well.

This dory will go together with 6mm sheet plywood for the sides and 9mm or 10mm of the same for the bottom. Let’s put a good, heavy bottom on her. She might not need the extra strength, but the additional inertia will calm her motion. Too-light skiffs dance around like dry leaves in the autumn breeze. Professional watermen put high value on steady platforms.

The layout shown on the plans seems about right for general use. It provides compartments in which to hide foam blocks that will keep the Coast Guard happy, and us solidly above water, should the worst happen. We might want to mount a 3 1⁄2′- high post at about station No. 6.

This stanchion (sissy bitt, chicken post, idiot bitt—call it what you wish) will offer a firm handhold when we’re standing and steering with a tiller extension.

As for finish, this dory won’t be happy with varnish and enamels. Let’s break out the latex house paint for the exterior. The interior will feel just right when bathed with a good oil…store-bought or home brew. This is one functionally beautiful boat—a waterborne World War II Jeep.

Plans from The WoodenBoat Store, P.O. Box 78, Brooklin, ME 04616; 800–273–7447, <www.woodenboatstore.com>. You can reach designer David Roberts at Nexus Marine Corporation, 3816 Railway Ave., Everett, WA 98201; phone 425–252–8330; <www.nexusmarine.com>.

Rugged and able, the San Juan 16 stands ready for hard work, or good fun, at the waterfront.

SeaHoss Skiff

SeaHoss Skiff Particulars:

LOA 15’2″

Beam 7’0″

Draft 6″

Weight 500 lbs

Capacity 1200 lbs

Power 10-30 hp

A workboat of strong character, the massively stable SeaHoss Skiff allows us to haul lobster traps, or most anything else, over her rails.

How about an honest workboat from the coast of Maine? Mark Murray designed and built this skiff for watermen who might need to hoist considerable weight over its rails. The strong sheerline produces a tall stem for standing up to the afternoon chop and yet allows for low freeboard back aft in the workplace. When you’re hauling a mess of traps by hand, each added inch of height amounts to bad news. And that purposeful sheer looks just fine.

Traditional sheet-plywood construction produces a quick building time and clean interior. The plans also describe a self-bailing option. As the day’s fishing ends, we’ll be able to blast the deck clean with a garden hose. Even better, we can sleep through three-day nor’easters without worrying that too much rainwater will sink our expensive outboard motor.

SeaHoss shows plenty of flat bottom and a straight run. When this skiff is lightly loaded, a small 15-hp engine will push it along at 16 knots on an easy plane. At that speed, the machine will drink about 3⁄4 gallon of fuel per hour. When full of the day’s catch, or other work, the tough boat will get home well enough at a slower pace.

Mark describes his boats’ performance: “These skiffs run reasonably dry in waves. I wish I could say that they don’t slap in a chop, but I can’t change the laws of physics. When they’re throttled back, I feel safe in nearly all conditions.” For those who would push a mite faster in rough water, he offers plans for a deadrise (V-bottomed) SeaHoss.

Plans from SeaHoss Skiffs, 314 Maine St., Brunswick, ME 04011; phone, 207–798–7976; <seahoss@gwi.net>

Sea Urchin

Sea Urchin, a particularly well-proportioned little skiff, can be rowed, sailed, or (with its nifty tent) camp-cruised.

Sea Urchin Particulars

LOA 11’6″

Beam 4’6″

Draft Not much

Sail area 54 sq ft

As general manager for Boothbay Harbor Shipyard, David Stimson has earned plenty of experience with large yachts, but on occasion he turns his talents to small boats. Sea Urchin came from his own shop several years back, and she’s a fine-looking little skiff.

David makes a strong case for a short (11’6″) skiff: “Two people can easily carry the boat, and it will fit in the back of a pickup truck—eliminating the need for a trailer. Lower materials costs should not be ignored.” He adds that Urchin’s small size makes her “ideal for children to mess about in.”

We might not think that such a tiny boat could work as a beach cruiser, but take a look at that cleverly devised tent—complete with picture window. It will provide cozy shelter for young adventurers.

The specified sprit rig was commonly seen on small American working craft. It is simple and requires only short sticks.

David and his apprentice built the prototype Urchin of cedar on oak. Can there be a wood more pleasant than white cedar? It takes fastenings well, glues well, works well, and has a satisfying aroma. It is soft. Cedar planks work into each other as they swell. They’ve been known to cure slightly imperfect plank bevels with no help from a builder’s hand. For nonbelievers, Sea Urchin’s plans include alternate specifications for sheathing the hull completely with sheet plywood.

Plans from Stimson Marine, 261 River Rd., Boothbay, ME 04537; 207–380–2842; <by-the-sea.com/stimsonmarine>

Chewonki Kayak

Simple in shape and structure, but fast and stable, the Chewonki Kayak makes for an ideal first project.

Chewonki Kayak Particulars

Length 19’3″

Beam 24″

Weight 70 lbs

This kayak is fast, stable, and easily built. David Lake modified the design from a native Greenland boat for Maine-based Camp Chewonki. Among other changes, he added 1″ to the breadth (a 4.35% increase) and specified traditional sheet-plywood construction.

Unlike most plywood kayaks, which go together stitch-and-glue fashion, the Chewonki boat employs chine logs and other structural members that help to make boatbuilding a pleasant experience. We’ll have to deal with many parts, but they’re simple to make and fit. And we can choose to apply various adhesives and coatings—some of which are less expensive and less toxic than others. Epoxy need not be used here.

David drew this kayak at the request of Camp Chewonki’s director. Every summer the teenage campers build their own boats, learn how to paddle them, and head east for a three-week expedition among the Maine islands. They often stop here at WoodenBoat and are among our happiest visitors. Each paddler displays well-developed boatbuilder’s vanity: “Look at how my coaming fits! And see the toggles on the grab loops? Much better than the other boats….”

If you’re looking for a rugged, fast, and (by kayak standards) brutally stable boat, the Chewonki kayak seems worth a close look.

Plans from Lake Watercraft, 26 Barrets Way, Woolwich, ME 04579; phone 207–443–6677;

<davidlake/lakewatercraft@yahoo.com>