A Beginner’s Guide to Boat Trailers

Trailering your boat opens you up to new frontiers in fun and adventure. It allows you to explore waters far from home, keeping the experience exciting and new. In the following pages, we’ll give you some trailering basics, including an overview of trailers and a good look at their component parts. We’ll also show you some pointers on hauling, unloading, reloading, and trailer upkeep.

Boat Trailer Types

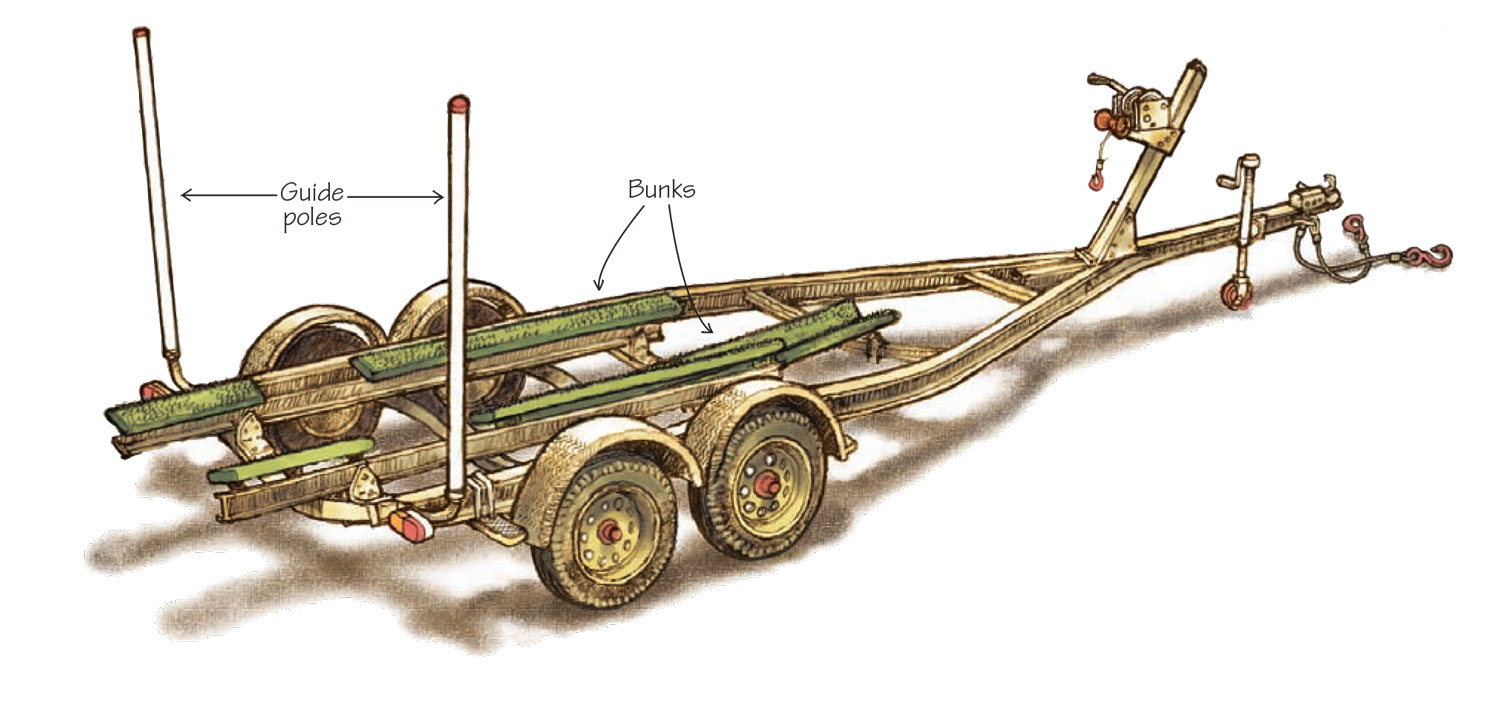

Boat trailers support the underside of the hull with either bunks or rollers. Sometimes the bunk trailer will also have keel rollers (see cover illustration), which are not meant to support the boat but rather to serve only as an aid in positioning the boat on the trailer.

Bunk Trailers

Bunk trailers are a popular choice among wooden boat owners. When using a bunk trailer, apply a bunk lubricant such as Liquid Rollers or Slydz-On to make sliding the boat on and off the trailer easier. Guide poles are also a helpful addition to any type of small boat trailer; they’re great for sighting the boat’s position behind the vehicle.

The bunk trailer is simpler and less expensive, and gives more uniform support. Bunks are often preferred by wooden boat owners. Bunks require the trailer to go deeper into the water—until the boat is nearly afloat—before the boat can be launched. That same depth is required for recovery. This can limit your launching options.

Roller Trailers

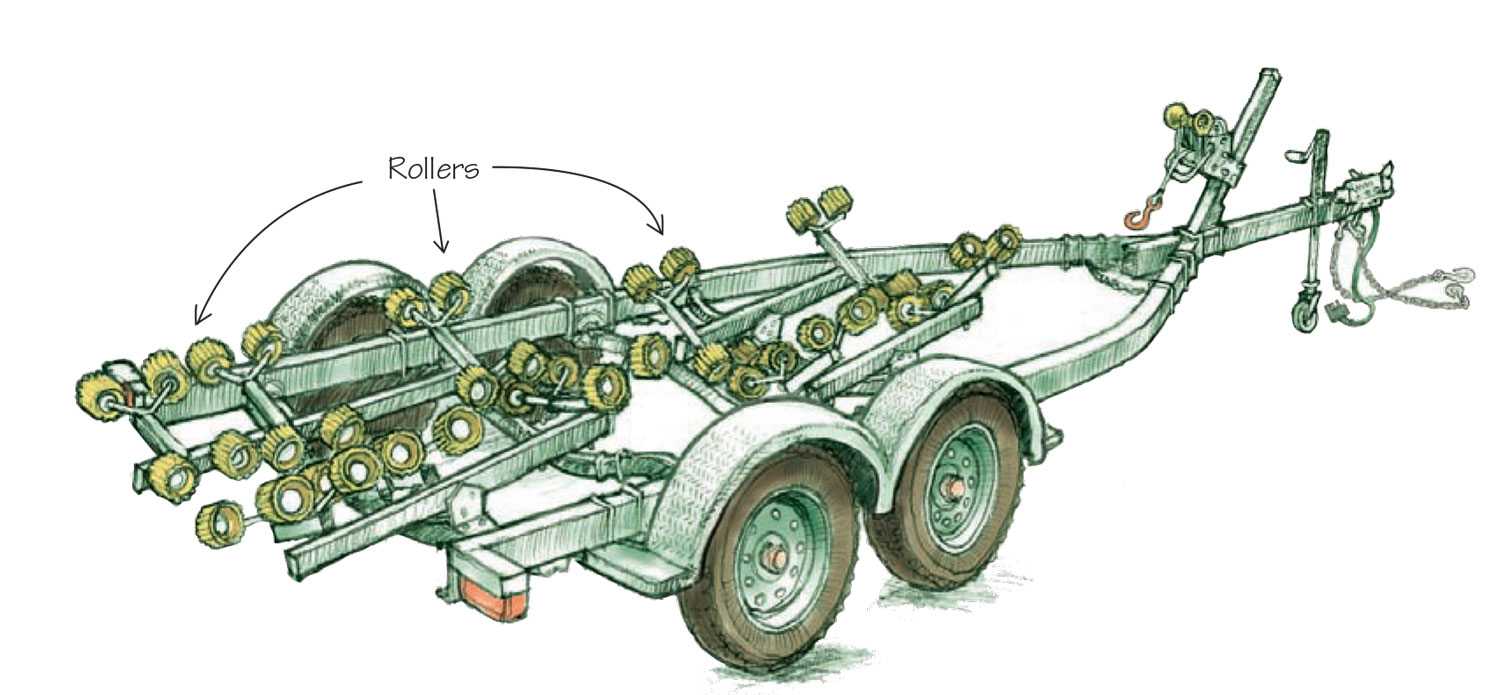

Roller trailers are a fine choice for thick-hulled boats. As long as the boat is properly aligned and supported, a roller trailer can be a pleasure to use, as it allows a boat to be launched and reloaded in shallower water than its bunk-type counterpart.

Rollers make sliding the boat off into the water or winching it back on a simple operation, but roller supports are more expensive, harder to maintain, and, in some cases, can damage a wooden boat, as each roller exerts a point load on the hull.

How Are Boat Trailers Made?

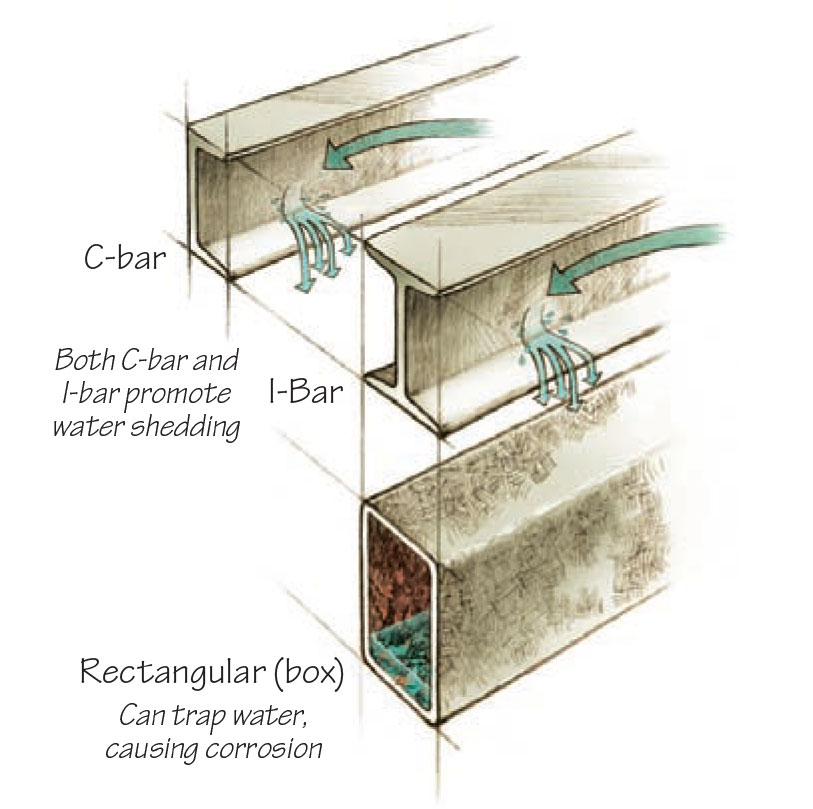

Commercially available trailers are almost universally made of steel, galvanized steel, or aluminum. A trailer with a painted steel frame is the least expensive but does not hold up well to saltwater use; however, it can be fine if used in fresh water exclusively.

Galvanized steel and aluminum frames are both good choices for salt water (both probably will still have galvanized steel axles and wheels). Aluminum is my favorite because it is lighter and more corrosion resistant than the other two, even though it is more expensive.

The configuration of a trailer frame’s tubing can also make a big difference in a trailer’s Longevity, as illustrated above.

Tongue Weight

Many trailer manufacturers recommend that 5 to 7 percent of the combined weight of the trailer and the fully loaded boat be supported by the hitch. To achieve the correct tongue weight, you can move the boat back and forth by adjusting the winch stand.

You’ll need considerable trailer weight on the back end of the vehicle to make the trailer stable on the road. If it starts seesawing side-to-side, it’s a sign of insufficient tongue weight, so build up speed slowly the first time out. Seating the boat fairly low on the trailer will also improve stability over the road and make launching and recovery easier on a shallow ramp.

On a bunk trailer, the boat’s transom should be on top of the supporting bunks; on a roller-type trailer, the transom should be very close to its supporting rollers.

Boat Trailer Components

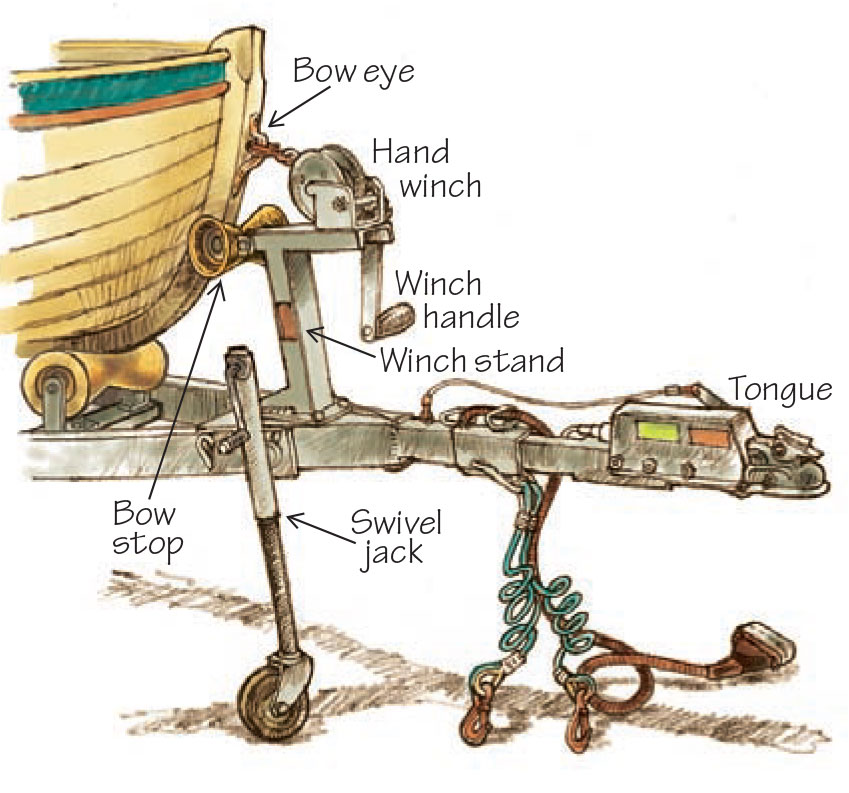

Trailer Winches

A trailer winch, which is mounted on a pedestal at the forward end of the trailer, comes in handy for pulling the boat back onto the trailer.

The winch strap or cable should be plenty long to reach the bow eye when the boat is still afloat, and it should be parallel to the trailer frame when the boat is being winched into position; this angle can be adjusted by loosening the bolts and moving the winch up or down on the winch stand, or by relocating the eye on the boat itself. Also, the cable should run fair and not bind on the bow stop—the little horizontal roller or bracket that the bow snugs tightly against.

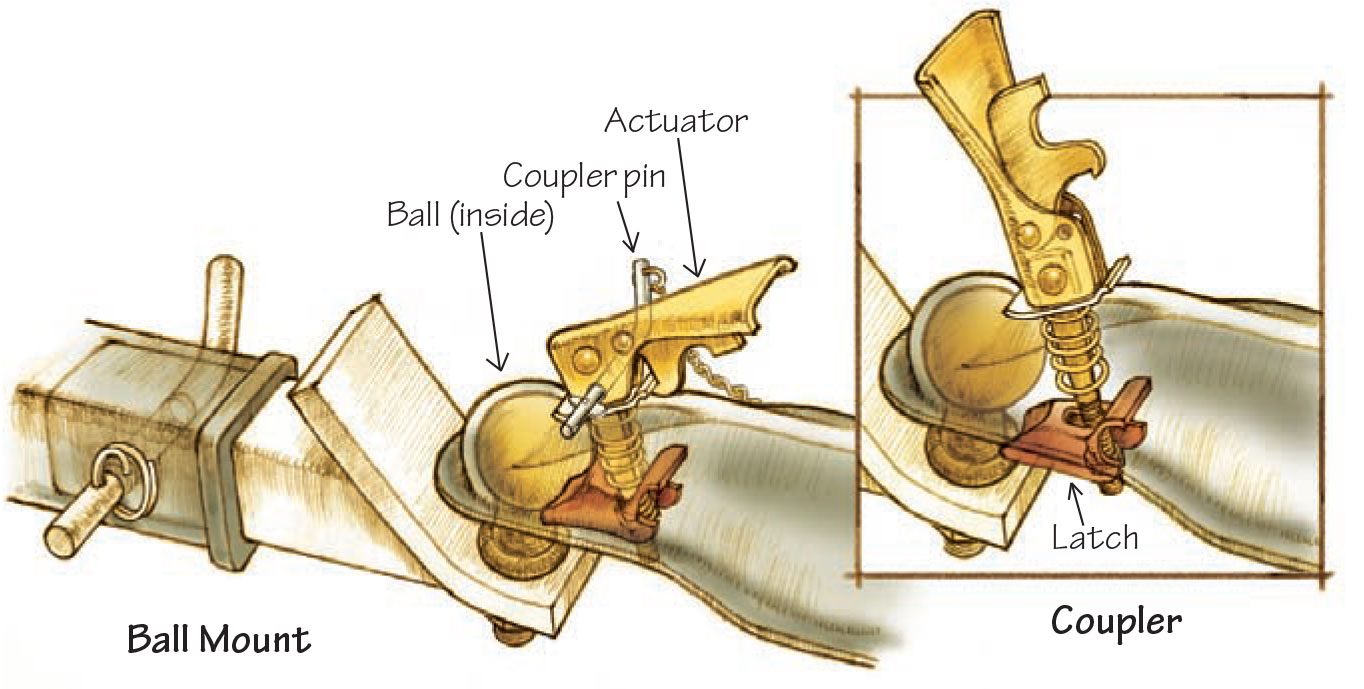

Ball-Hitch Mechanisms

The best type of hitch to have installed is one that transfers the load directly to the vehicle’s frame. Make sure the trailer coupling is the same size as the ball and drops down and fits securely over it; then hook up the coupler pin or hitch lock to keep it there.

After the trailer coupler is lowered onto the ball, the spring-loaded actuator is pushed down to secure the latching mechanism, and then a securing pin is inserted to prevent the actuator from popping back up unexpectedly. The coupler must drop all the way down on the ball so the ball is completely inside it and so the latch can be secured under the ball. Make sure the coupler and ball are the same (mating) size.

Finally, cross and attach the backup cables or chains to the hitch in case the trailer becomes detached from the ball.

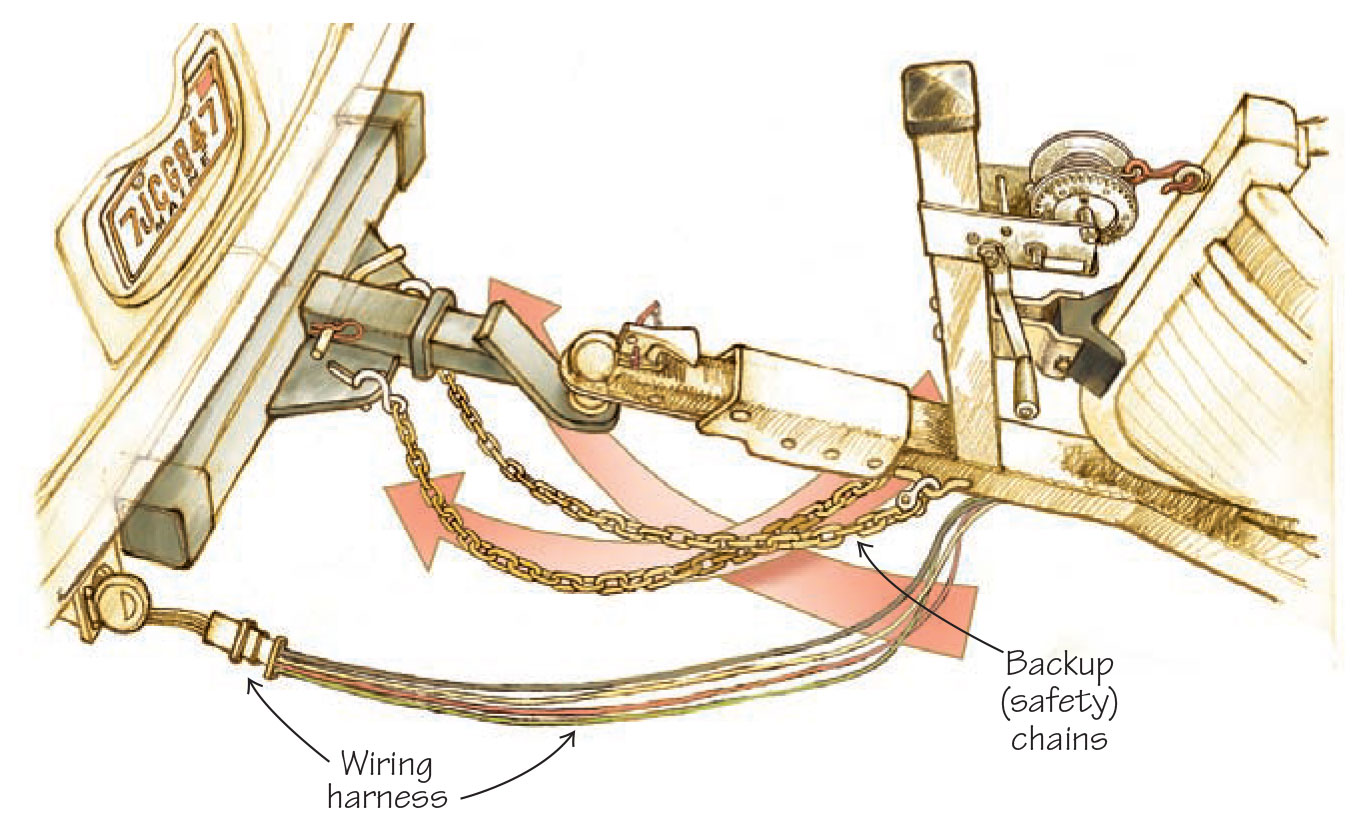

Saftey Chains

Safety chains are crossed to opposite sides and hooked onto the trailer hitch on the vehicle to prevent the trailer from coming completely detached if the coupler fails. The chains should be long enough to allow the trailer tongue to travel freely in a hard turn, but not so long that they drag on the ground.

Wiring and Lights

The wiring harness on the trailer must plug into the vehicle’s socket for the lights to work. If the plug and socket don’t match, you can buy an adapter that can be used to hook them together. After you hook up the harness, ensure that all of the trailer’s lights are working. They are notoriously unreliable, so check your lights often.

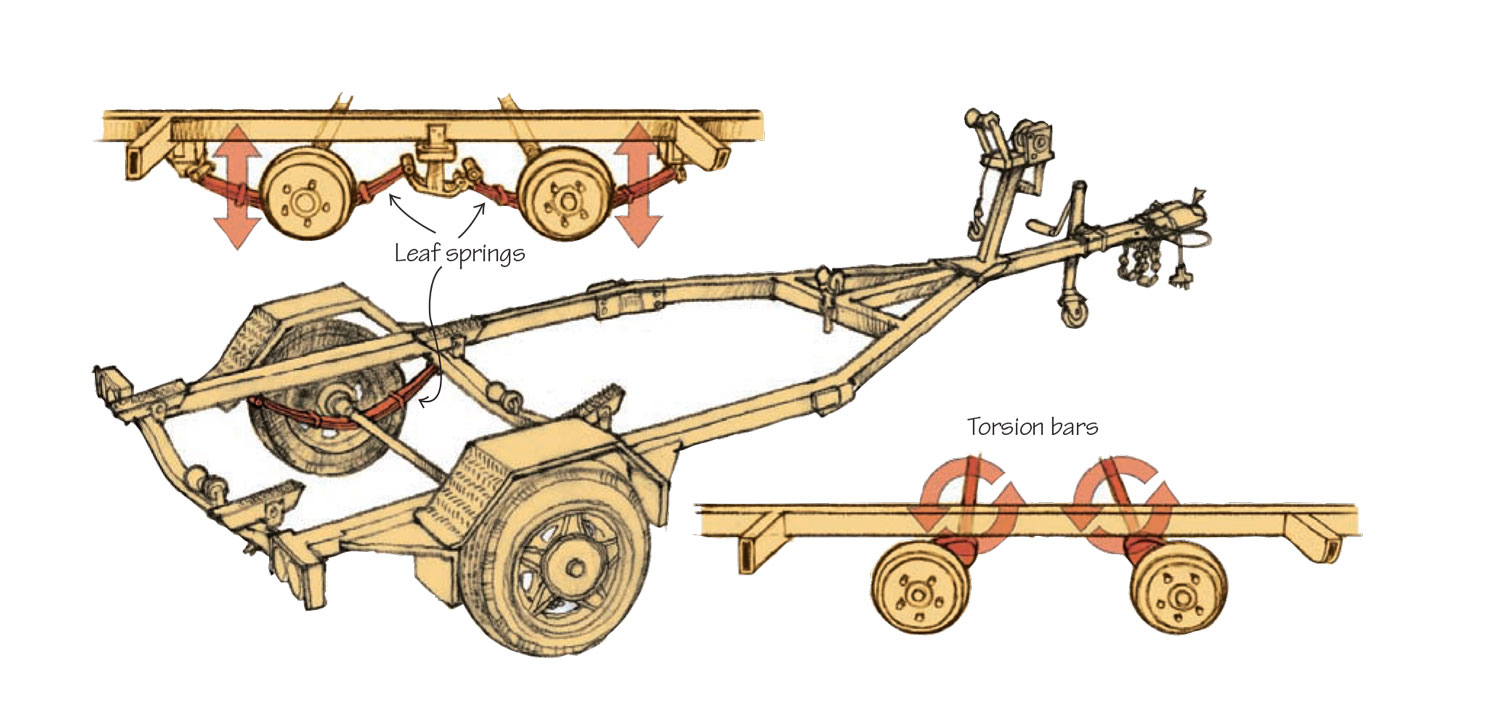

Suspension and Brakes

Boat trailers usually have a suspension system made up of leaf springs just like cars used to have (and as many trucks still have in the rear). Some trailers have torsion bar suspension, which is also used on many trucks and SUVs; this mechanism is basically a steel bar twisted along its long axis that serves the same purpose as leaf springs.

For larger boats, it should also have its own brakes, as your vehicle’s brakes are not designed for the additional weight of a heavy trailer.

Brake Operation

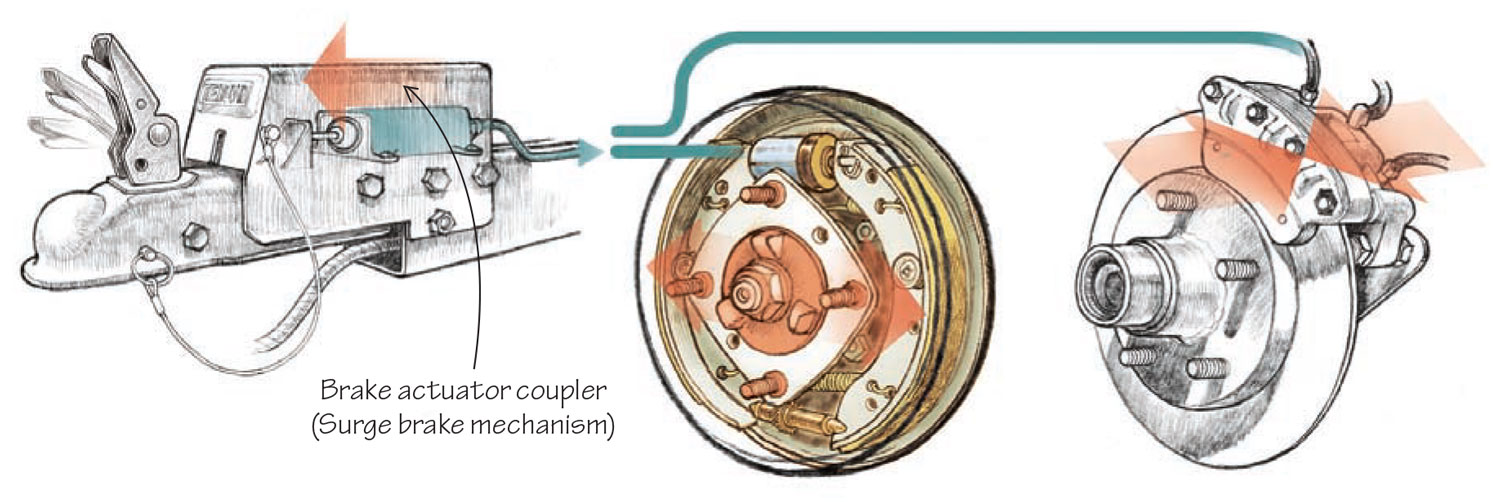

Many states require trailer brakes if the rig is over 3,000 lbs. Trailer brakes can be either electric or surge type.

Electric brakes, which are found on comparatively few trailers, engage simultaneously with your vehicle brakes. Their sensitivity, or amount of stopping force, can be adjusted to suit the load. Unlike their surge-brake counterparts, electric brakes work when backing the trailer down a launch ramp.

Surge brakes activate mechanically when you hit the brakes and the trailer begins to surge forward against the trailer hitch. This type of system is used on most trailers. When the tow vehicle brakes are applied, the mechanism slides forward against an actuator and applies the trailer brakes.

Whether or not your trailer has its own brakes, you should make sure that your vehicle’s brakes and emergency brake are in good working order before you hit the road.

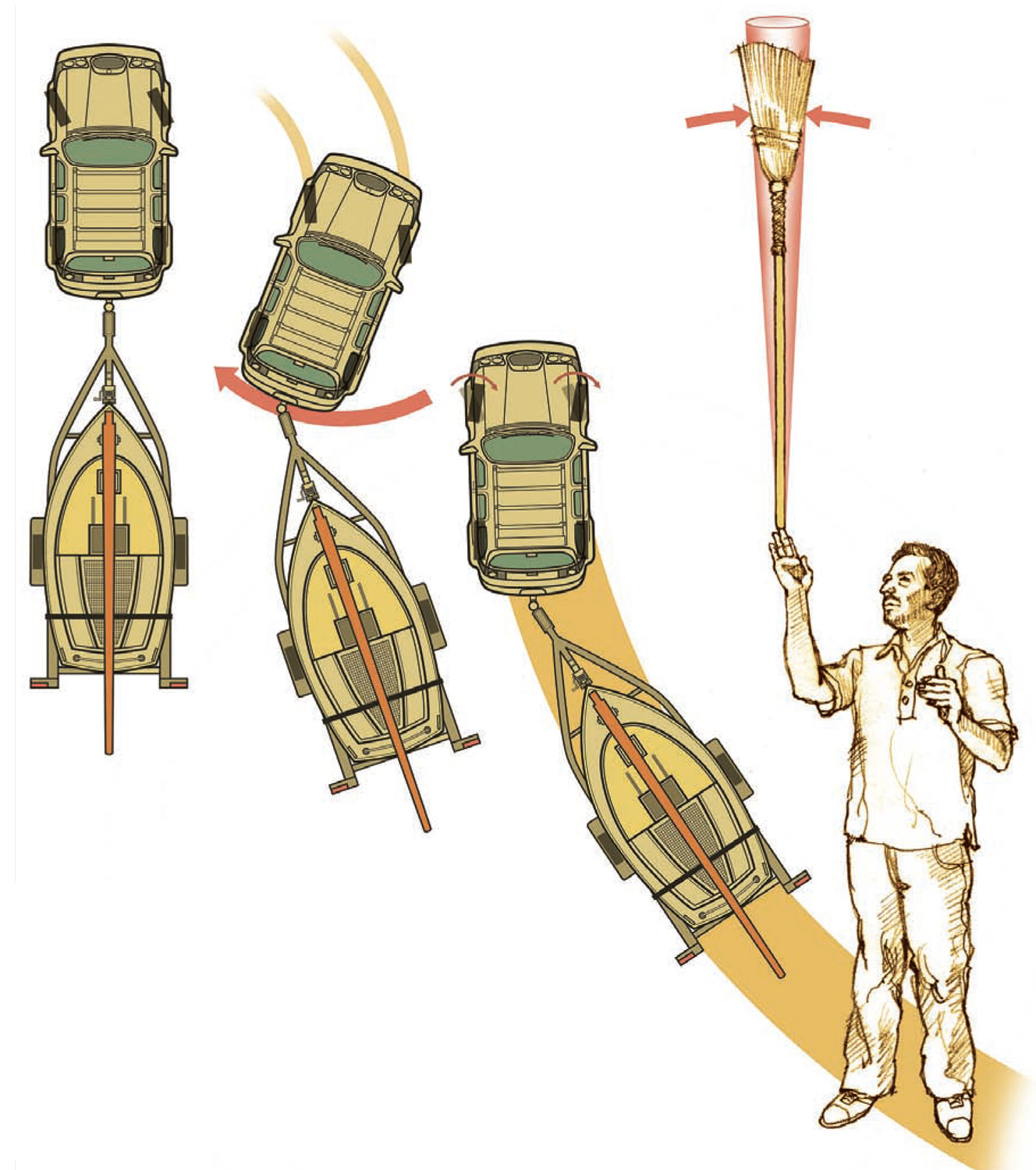

How to Launch and Reload Your Boat

Like the man balancing the broomstick, when backing a trailer, slight movement at one end causes dramatic movement at the opposite end. In order to back a boat trailer to the right, turn the vehicle’s steering wheel to the left. Once the boat is tracking on the desired line of travel, straighten or correct the course to the left by turning slightly to the right. If you’ve turned too hard or you find that you have overcompensated when correcting, pull forward and try again.

Learning to tow a boat behind your car or truck is best done at dawn in the privacy of a parking lot where there’s plenty of space and no audience. Be sure to practice backing up and making wide turns before hitting a crowded launching ramp on a Saturday morning.

You’ll want to have the boat on the trailer when practicing, since without the boat you won’t be able to see where the trailer itself is most of the time; this will also give you a better feel for the boat’s weight in relation to your vehicle. Be sure to strap the boat down to the trailer. Usually a heavy nylon strap goes from the trailer frame on one side, up over the boat, and back down to the other side of the trailer frame, where it is attached and tightly cinched.

Prior to launching, make sure that there’s enough water depth for your boat to float in behind the trailer (and that there will be enough water at the time of recovery, if tides are involved). In preparation for launching, enlist the help of a competent partner who can remove the gunwale tie-down strap that secures the boat to the trailer and then can either back the boat off the trailer, if it is a powerboat, or use the bow line to pull it over to the dock if it’s unpowered or is impractical to power off the trailer.

A few precautions: Be sure you’re the only one in the car when backing down the ramp; if you should lose control, you don’t want anyone—especially children—to be trapped inside the vehicle. Make sure that the transom plug is in securely, and remove the gunwale tie-down strap just before getting into position on the ramp.

Also, if you have guide poles aft on either side of the trailer, don’t hang any fenders over the side, unless they’re aft of the poles—otherwise, you’re apt to hook a fender and take one of the poles with you. You’ll want to have a couple of docklines handy so you can tie the boat off while waiting for passengers.

With the wiring harness unplugged and winch cable disconnected, you, the driver, slowly back the trailer down the ramp until the stern is nearly touching the water (no abrupt stops!). Then the person driving the boat starts the engine (with the lower unit, if there is one, down in the water far enough for the cooling pump to achieve suction), while you continue to back the trailer until the boat is afloat. The boat driver backs the boat off, after which you drive ahead, pulling the trailer up the ramp and over to the parking lot.

Recovery is similar, but in reverse. In this case, the vehicle driver backs the trailer down until the trailer wheel fenders are just a couple of inches higher out of the water than when the boat floated off.

Then, after the boat driver makes sure all the fenders are inside the boat, he drives the boat onto the trailer with just enough speed to maintain steerage. He needs to adjust for the wind and current before he gets too close to the trailer, and may be crabbing until the last couple of feet. Just before touching, he’ll spin the wheel over to straighten the boat out as he slides up the trailer.

Once aboard the trailer, he’ll either power all the way up or turn off the ignition, jump out, hook up, and winch the boat up the last few feet.

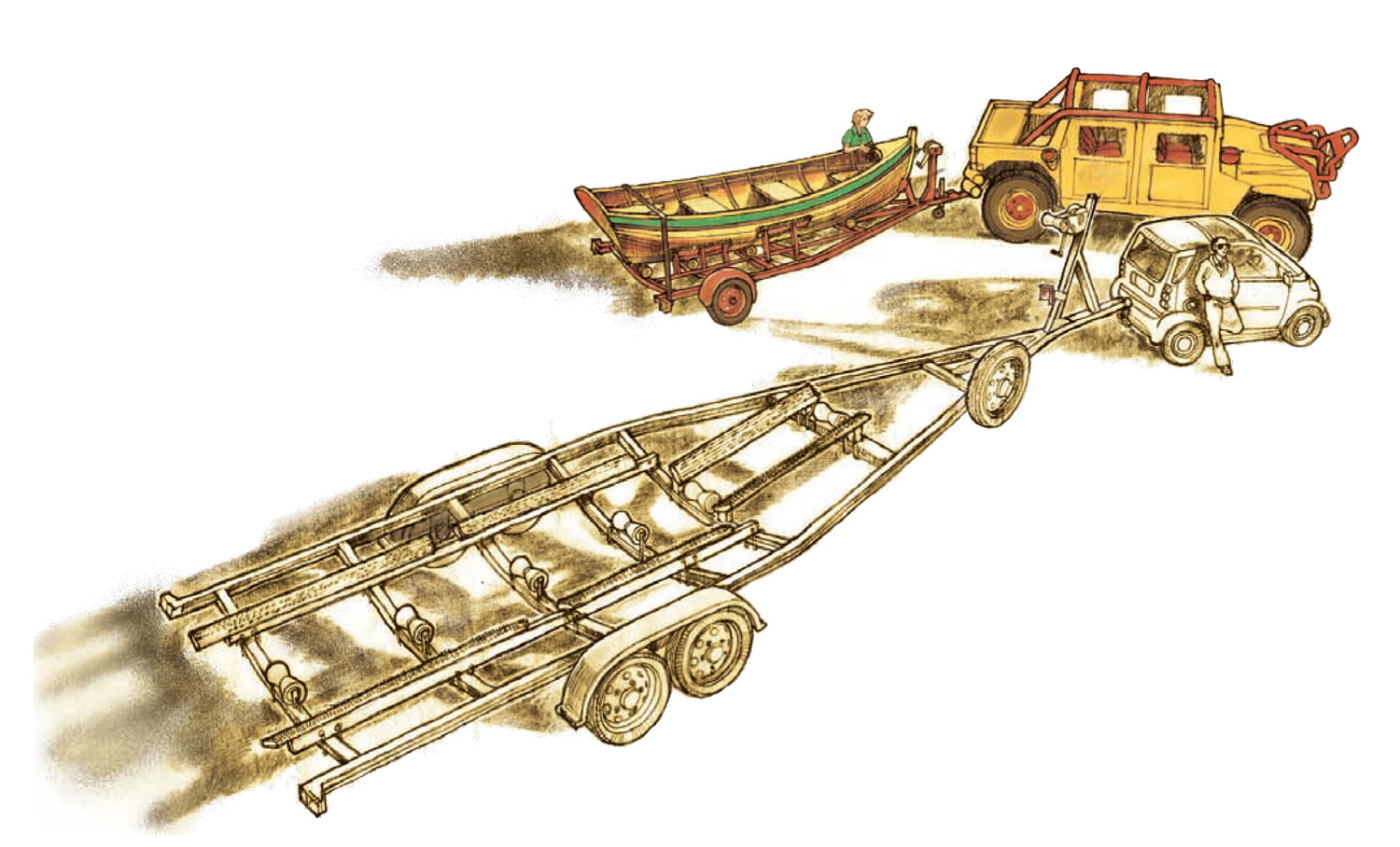

Picking the Right Vehicle to Tow Your Boat

Though depicted in the extreme, the man in the foreground lacks the forethought that many boat owners share in terms of vehicle selection when pairing a vehicle to its trailer. The large vehicle and small boat behind it are an exemplary pairing that will provide safe and comfortable travels.

It’s important to be able to make a quick and controlled stop. Make sure you have a car or truck that is rated to tow the combined weight of your boat, fully loaded, and the trailer. Getting a bigger vehicle that can tow, say, 30% more than your loaded boat and trailer weight, provides a nice safety margin.

If buying a vehicle, get the tow package, as it likely includes a transmission cooler and a deeper drivetrain ratio for more towing power. Also, a vehicle with a longer wheelbase is more stable, as a rule, than one with a shorter wheelbase.

Boat Trailer Upkeep

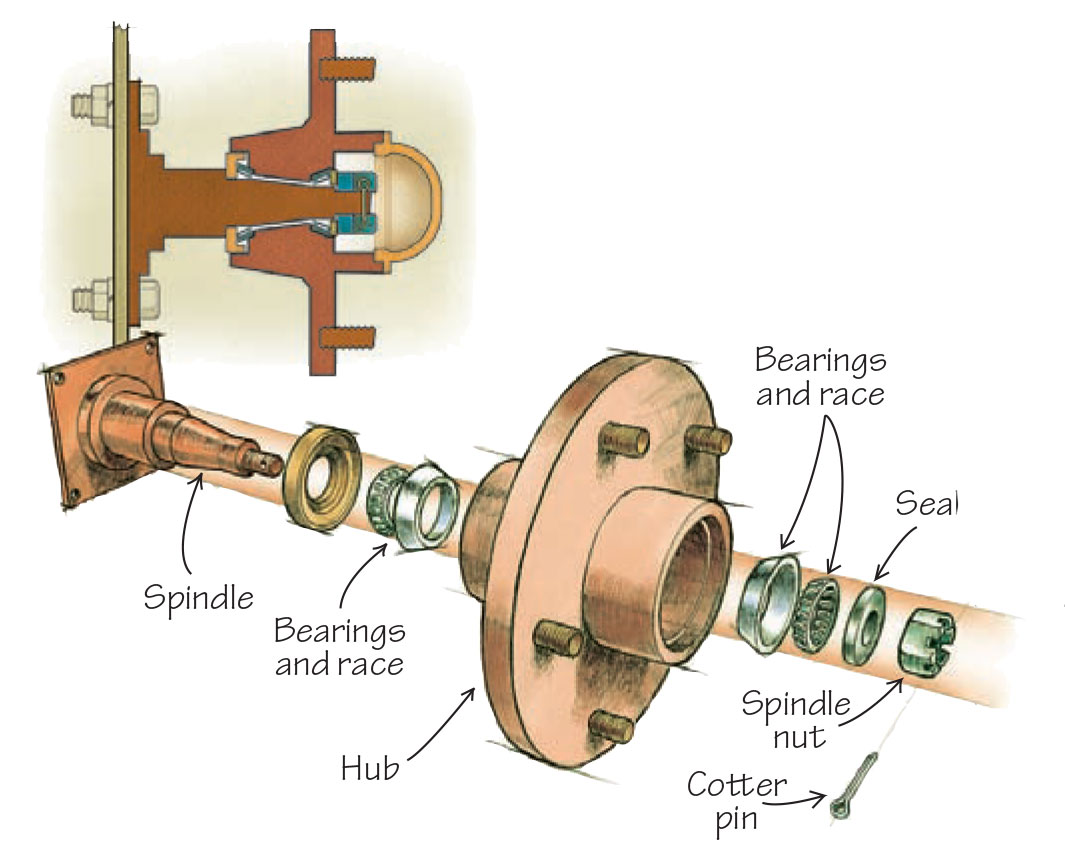

Trailers require routine maintenance. If you’ve launched in salt water, be sure to hose the trailer down with fresh water. Keep after the lights—inspect them every time you use the boat. Check the tire pressure and the lug nuts. Also, be sure to inspect the wheel bearings at least quarterly (some owner’s manuals recommend greasing after each use in salt water). Bearings should be repacked at least once a year.

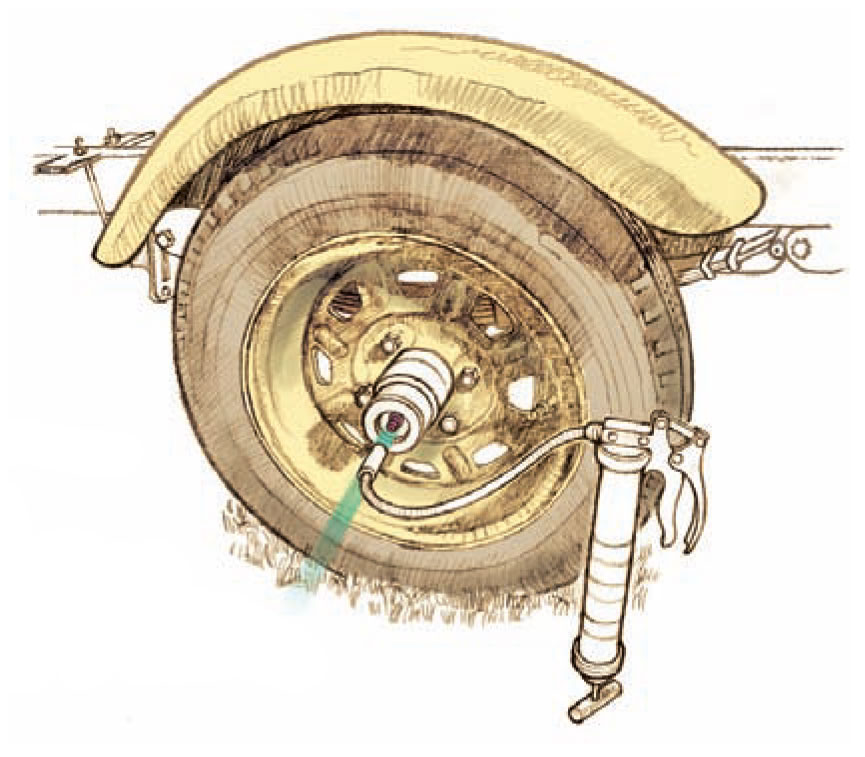

It is especially important to keep wheel bearings clean. They require occasional repacking with the manual’s specified lubricant (such as a lithium-based marine trailer bearing grease) at the intervals specified by the trailer’s manufacturer. Some trailers have oil bath systems that must be kept filled to the proper level.

To keep things running smoothly, grease the bearings often. Connect a grease gun to the grease fitting (or Zerc fitting) and pump grease into a spring-loaded chamber. The spring subsequently pressurizes the grease so it is continually applied to the bearings while the trailer is in use, providing lubrication and sealing water out of the bearings.

When Trailering a Boat, Safety Is Key

We tow our 6,000-lb boat across several states every summer. There’s just no getting around the fact that there’s more risk with a heavy boat behind you at highway speed.

Bone up on regulations before you cross state lines. For instance, many states have lower speed limits for vehicles towing trailers. There is much more to learn about safe trailering than there’s room for here; this is just a start. Thoroughly read the literature produced by your trailer manufacturer, and ask lots of questions before hitting the road.

Learning to use and maintain your trailer properly is well worth the effort. You’ll have peace of mind as you venture to previously unknown waterways. Now get out there and have fun!

For more on safely trailering a boat, check out these articles:

– Going Down the Road: A guide to trailer safely

– Boat Trailering Tips: Safe towing to the ramp and back

– Living with Little Boats: A guide to orderly storage and transport

Eric Sorensen is an ex-coastguardsman, Navy ship driver, licensed master, and longtime boat owner. He consults with boatbuilders and commercial shipyards to improve vessel design, construction, and performance.