Photo by Alison Langley, illustration by Dan Thornton after R.D. "Pete" Culler

Photo by Alison Langley, illustration by Dan Thornton after R.D. "Pete" CullerMaine Maritime Academy Instructor Molly Eddy shows student Zoe Ciolfi the finer points of oarmaking, using author Andy Chase’s methods adapted from those of R.D. “Pete” Culler.

In his book Boats, Oars, and Rowing, Pete Culler discusses what makes a really good pair of oars, and how any modestly skilled woodworker can make their own. To row with a really nice pair of oars in a decent rowboat is not just good exercise; it’s good therapy, as well. Combining Culler’s advice and my own experience, I present the following guidance:

- To help balance the oar, leave the shaft square or octagonal from the leather to the handle, and remove as much wood as possible from the blade end. I prefer the look of octagonal, though the square version would put more weight above the oarlock, where you want it.

- Unless you are a competitive rower (or pretending to be), you don’t need spoon-bladed oars. When you dip a spoon-bladed oar in the water, it pretty much stops and you must pull the boat past it. That’s a lot of work. The rest of us need our oar blades to slip a little at first, so make your blades long and narrow. Once you get your boat moving, the blades won’t slip much, but it’s a lot easier to get things moving with a blade that slips a bit, initially.

- To lighten the oar below the leathers, Culler makes the shaft go from round right at the leathers to oval as it approaches the blade. In fact, you’ll notice that there is a straight taper from the handle all the way to the end of the blade when viewed from the edge of the blade. Such an oar would be pretty easy to bend sideways, but not in the direction of pull.

- Continuing that idea, Culler scallops out the blade on either side of the center ridge, again to remove excess weight wherever possible outboard of the oarlock. This also happens to make a very pretty oar.

- Finally, note the shape of Culler’s handle: it is much more comfortable than a stock oar’s barrel shape, and it also keeps your hand securely on the oar. If you have large hands, you might want to increase the diameter by 1⁄8″.

Having learned all the above, a few years ago I made a pair of oars. As typically happens, I learned a few more things in the process. The first was (after leathering and varnishing and admiring a truly lovely pair of oars) that my new oars didn’t fit in my oarlocks. So, I gave them to my nephew, who had just built a lovely rowboat with tholepins. The second thing we both learned was that my new oars warped in a short time. I had laminated two 2×6s from lumberyard stock, but they warped in the direction of pull.

With that in mind, I hit on the idea of gluing up a four-way lamination in such a way as to force the laminates to resist each other when trying to warp, thereby canceling out that tendency. This worked perfectly, and I discovered that it added a fringe benefit: As you’ll see, it gave me two permanent, perpendicular centerlines that helped immensely in keeping my work straight and true throughout the construction.

My second pair of oars came out very nicely and are still straight and strong five years later. The problem of fitting into the oarlocks was resolved by slimming the oar shafts by 1⁄4″ from Culler’s plans. This will be necessary if you’re using standard No. 1 pattern oarlocks.

With this success under my belt I made two more pair for a large rowing tender my brother built. This boat was big and beamy, and he asked for 9′ oars. I simply lengthened the shaft but didn’t alter the other dimensions. All four oars were broken during the first season, so I learned something there, too. When making new ones the next winter, I restored the 1⁄4″, which required using the more expensive No. 2 oarlocks, and those oars are now holding up well after three seasons.

I also made a pair of 6-footers, and in this case, I kept all the dimensions the same as the first pair, except the length. This makes proportionally hefty oars, but they’re very serviceable and still quite handsome. So, in the end, you can make 6′ or 7′ oars by reducing the maximum diameter by 1⁄4″. For 8′ or 9′ oars you’ll need to stick to Culler’s dimensions and buy No. 2 oarlocks.

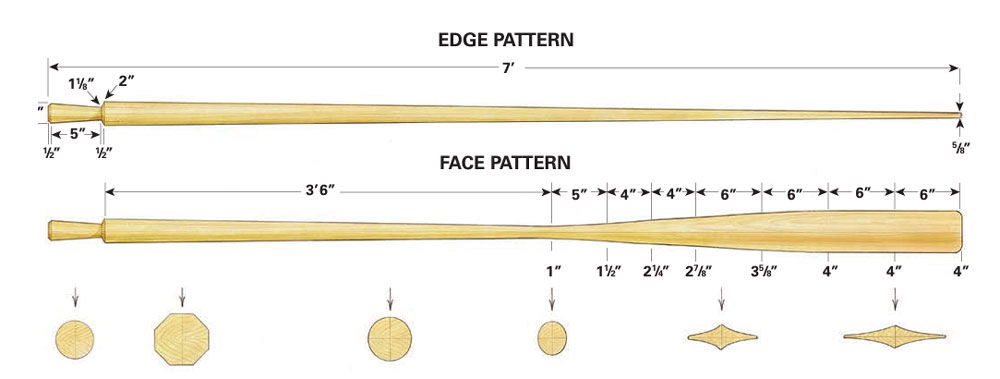

Dan Thornton, after R.D. "Pete" Culler

Dan Thornton, after R.D. "Pete" CullerCuller’s pattern is for 8′ oars, but I used the same dimensions for a 7′ pair and a 6′ pair, except that I reduced the loom diameter by 1⁄4″ in order to fit No. 1 oarlocks. I also made a 9′ pair by simply changing the length of the loom, but maintaining the original diameter.

How to Make Wooden Oars in 20 Steps

G. Andy Chase

G. Andy Chase.

1. To begin gluing up the oar blank, first the 2×6s are glued together to make a 4×6. When the glue has cured, either run the edges over a jointer, or stand them on edge and run them through a thickness planer to get clean edges for the next step.

2. The resulting 4×6 is ripped into halves. Here, one of the pieces has started to warp. This will be taken care of by gluing it to a new partner. If you have two pieces that are bowed, glue them so the bends oppose each other.

3. Note the opposing end-grains as the pieces are shuffled and about to be glued back into a new 4×6. During the process of shuffling pieces, I marked them to indicate which end would become the blade, so I didn’t get mixed up in the gluing frenzy. This was important because I had a couple of bad knots to work around. Remember: you’re making two oars, so will have two 4×6s; once they are ripped you have several choices of which pieces are glued to which. Use this variety to place flaws outside the area that will end up in the finished oar.

G. Andy Chase

G. Andy Chase.

4. Using a chalkline, mark out the straight taper from 2″ at one end, where the handle meets the loom, to 5⁄8″ at the other (blade) end. Then cut this out on the bandsaw, as close to the line as you dare, and trim to the line with a hand plane. But don’t cut the handle yet.

5. Now, mark out the outline of the oar using the dimensions from the pattern above and cut it out on the bandsaw. Using a hand plane, power hand plane, spokeshave, and sander, trim to the drawn line. Again, don’t cut the handle yet. The reason for this is that it will give you a place to clamp in the vise while working, and thus you won’t be damaging the finished oar. Note that once you have planed the oar square, you have four finished surfaces. At that point you must be careful to not dent or scratch the oars.

6. These oars will be eight-sided for a length of 14″ from the end of the handle, then they become round, then they gradually transition to oval just before opening up to the blade. A simple homemade ruler allows you to mark off points to create lines that will guide the eight-siding of the tapered oar blanks, as shown; the outer marks on

the ruler align with the outer edges of the developing oar blank; the inner marks automatically adjust, proportionally, as the ruler is placed at different locations along the oar. Alternatively, you could use the spar gauge shown in the sidebar for this step. The spacing of the pencils shown in the sidebar is also the spacing of the points on the ruler; use that drawing as a guide if you choose to make a ruler.

7. Initially, the entire length of the loom is eight-sided. Plane away the corners to the marked lines to create this shape. The portion of the oar seen here that’s clamped in the vise will be cut away to make the handle, so the dents won’t matter.

Drawings by G. Andy Chase, Photo by Alison Langley

Drawings by G. Andy Chase, Photo by Alison Langley.

8. Mark the edges of the blade to the finished dimension of about 3⁄16″. Roughly plane the blade, leaving a middle ridge at the full dimension. Carpenter’s chalk helps to keep track of progress.

G. Andy Chase

G. Andy Chase.

9. Using a curved rasp (shown here), or a curved-bottom plane or spokeshave, hollow out the faces of the blade. This removes unnecessary material, and thus weight, from the blade end.

G. Andy Chase

G. Andy Chase.

10. After roughing out the hollow with the rasp, finish this portion of the blade with a sheet of 80-, then 120-grit, sandpaper glued to a rounded piece of wood.

11. Finish the edges and tip of the blade to a shape that suits your eye and intended use. For a rough-duty oar, leave it a little heavier to absorb some abuse. For a really pretty and light blade, take it down as thin and delicate-looking as you dare.

12. Mark the point at which the oar will change from eight-sided to round. Then, in the portion that’s to be rounded, plane away the corners, by eye, that resulted from the eight-siding operation to make a 16-sided loom. Finally, plane and sand this portion round.

G. Andy Chase

G. Andy Chase.

13. Carefully mark out the handle. You will be cutting out a square that tapers from 15⁄8″ to 11⁄8″. You’ll end up with a lot of lines if you mark them all at once, and it’s very easy to become confused when you go to the bandsaw to make the cuts. It’s safest, therefore, to mark two parallel sides of the handle, cut two cuts, then mark and cut the remaining two sides.

14. In this photo, two cuts have been made, but the offcuts have not yet been removed. Leave them in place for now, awaiting the final cuts, because doing so helps to support the handle on the saw table when making the subsequent cuts. Now mark and cut the second two.

G. Andy Chase

G. Andy Chase.

15. Here, the four longitudinal cuts have been made and the offcuts have been removed.

16a and 16b. The handle tapers from 1 5⁄8″ at the very end to 1 1⁄8″ at the end nearer the blade. Like the oar’s loom, the handle progresses from four-sided, to eight-sided, to sixteen-sided, to rounded—the final step accomplished with a chisel and coarse sandpaper. The resulting shape is very comfortable in the hand, and the taper helps you keep a grip on it.

G. Andy Chase

G. Andy Chase.

17. Here I’m cutting a radiused transition from the handle to the loom—a detail that avoids having a stress concentration where the handle starts. The duct tape protects the nearly finished handle from accidental chisel marks.

18. The final step in shaping the handle is to bevel its corner and to sand it smooth.

19. Sand the entire oar to 220-grit, and you’re ready for varnish. Follow these varnishing basics for the best outcome.

G. Andy Chase

G. Andy Chase.

20. Apply eight coats of good marine varnish before leathering.(Alternatively, the oars can be painted or oiled.) Do not varnish, paint, or oil the handles; they should be left bare so they will absorb sweat and water while you are rowing, and not become slippery.

21. The finished oars, varnished, leathered, and seasoned by a few years of use.

6 Steps to Leather Your Finished Oars

Culler recommends a leather that’s longer than what you find on commercially available oars. My leathers are 14″ long, though 12″ is ample. Do not tack the leathers to the looms, because fastening holes will weaken the oars. The leathers should be sewn on, a process that is easy and satisfying.

G. Andy Chase

G. Andy Chase.

1. Begin by measuring the circumference of the oar at each end of the leather, and cut out a piece of leather to fit these two circumferences. Get a feel for how stretchy your particular leather is, and make the piece smaller to allow for this.

2. Leather will typically stretch about 1⁄4″, but this piece was a full 3⁄8″ too narrow. Still, I was able to stretch it to fit while stitching. Not all leather will be so stretchy, though. Culler recommends soaking the leather before sewing. I found that when I did, the thread tore the holes. Working with dry leather and just pulling it tight worked fine for me.

G. Andy Chase

G. Andy Chase.

3. Mark off stitches at 1⁄4″ intervals, and about 1⁄8″ from the edge of the leather. Consistency here is a key to a tidy job.

4. Punch a hole for every stitch. Ideally, you’ll use an awl for this indispensable step, but if you don’t have one, use your needle.

G. Andy Chase

G. Andy Chase.

5. I used barge cement, a rubber contact cement used in shoemaking, to hold the leathers in place while I stitched. It worked well, and any rubber cement will work for this, but I caution you to not glue the whole leather to the oar. The glued portion can’t stretch—only the unglued portion can—and you need that stretch for the leather to fit tightly so it doesn’t slide on the loom. Apply just a line of glue down the center of the leather.

6. Use a baseball stitch with waxed sailmaker’s twine threaded through two needles, as shown here. Since the two needles will be at the two ends of the same piece of thread, you don’t need a knot at the start. When you get to the end, finish your stitches under the leather and tie a square knot under there where it won’t show, and won’t chafe away. You can put a drop of glue on the knot for extra protection. At every stitch, you’ll pull it tight, and it will open right back up again. Don’t worry about this; just keep doing that, and the stitches about 1″ back from where you are working will finally stop opening back up and stay tight.

7. With eight coats of varnish applied and the leathers completed, the oars are now really all done.

For more guidance, watch this video on the process of leathering oars.